“It’s your birthday today, Erik,” she said.

“Birthday?” he said. He knew what that was, he just couldn’t… make it… be… words.

He thought maybe it was going to be loud and lots of things and he didn’t like that for today.

“I think maybe we’ll have more birthday when you’re feeling a little better, but we’ll have some today,” she said. She was helping him with his clothes.

He could do his clothes, only sometimes he got lost along the way and he’d come out with his shirt half-buttoned and they had to fix him. So she would come help him and make sure he got it right the first time.

He couldn’t remember if he woke up or she woke him up. There were times for things and that helped. He wanted a… a thing that said the times, but they couldn’t have one.

“Okay,” he said.

It was dark here because the… glass…

Glass? Not the glass?

Was…

Closed…?

“Let’s see if we can find your shoes,” she said.

She was quiet. Sometimes they were quiet… because… sleeping. Sometimes they weren’t quiet… because… mad. She nudged the other bed on the way over, but the body in the bed didn’t move or talk.

“There they are. Erik, finish your buttons.”

“Yes…” He managed them slowly, one after the other, until there weren’t any more.

“You’re my auntie,” he said.

“Yes.”

Words for people were hard. Words for everything were hard, but words for people were hard and important. He had to say them because he couldn’t draw them. She was more than just “Auntie,” but if he asked her for the right word, she might think he didn’t remember her at all.

He didn’t want that, and he couldn’t explain to her about it not being that, so he didn’t ask.

“It’s my birthday,” he said. He’d have to remember “birthday,” he was going to need the word to talk about it.

“Yes.”

“All day?”

“Yes.”

He sighed. “Okay.”

◈◈◈

The other room was bright and cold and sudden, and that always scrambled him a little.

They had merged something wavy-metal over the big hole, and that kept out the wet and the wind, but not the cold

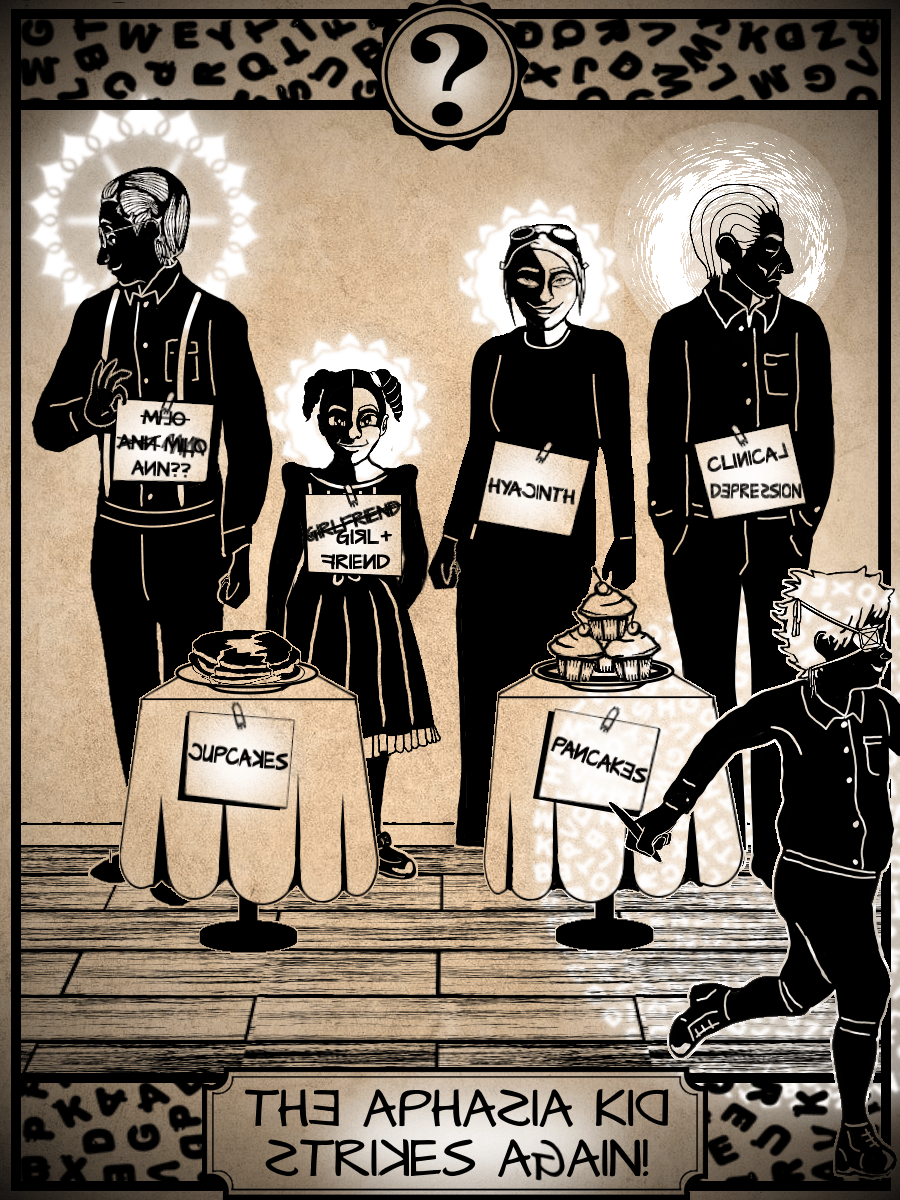

Someone said, “happy birthday,” and he said… he said, “okay,” and someone said, “breakfast…” And breakfast was… this plate. This plate. These things on this plate. He liked an egg but it wasn’t that.

They were round.

He knew what they were but he couldn’t say them unless they said it first.

“Please say it again.”

“Pancakes.”

“Pancakes,” he said. “I know it. I can. I just can’t… I just can’t… word, the word…”

“Say it?”

“I can’t say it.”

They were all right. They were soft. There was butter and syrup. He didn’t like how he couldn’t say them, though.

There was a man at the table. He had glasses and suspenders. He didn’t like to look at people. He didn’t like the newspaper either. He looked at his plate and he ate… round… things… quickly. He had to go to work today.

“You’re my auntie,” Erik said.

The man looked up, he glanced around, and one corner of his mouth twitched weakly, like maybe a smile or maybe just something wrong with him. He covered his mouth with a hand, considering, then he shrugged.

“Milo is your auntie sometimes,” Hyacinth said. She leaned in and speared another… another thing for her plate.

Hyacinth, thought Erik. He wished he could write it down. Auntie Hyacinth.

“Ann is my uncle,” Erik said.

“Ann is your uncle?”

That didn’t sound right. “Ann is my auntie. What did I say? I mean auntie.”

“Milo is complicated,” Hyacinth said. “Don’t worry too much, Erik.”

Milo looked sad at him, or maybe ashamed. He got up and put his plate in the sink. He didn’t come back to the table.

“Milo doesn’t talk,” Erik hazarded. He thought he remembered, but he wasn’t sure if it was always.

“That’s right.”

“Maybe it’s better,” the boy said softly.

“It’s definitely not,” said Hyacinth.

“I think Ann talks so much, Milo doesn’t have any words left,” the girl opined.

Erik looked over at her. She had dark brown hair. She had a blue dress. She had lots of blue dresses. He had those words and that memory but he needed a word for her.

“You’re my… my… girlfriend?” he said.

She drew back from him, shaking her head. Her pigtails bounced. “Uh-uh.”

“Just friends,” said Hyacinth. “You’re too little for girlfriends. Your Uncle Mordecai would scour me within an inch of my life if you went back saying you had a girlfriend.”

“I’m six,” he said.

No.

“I’m seven,” he said.

“Wait for seventeen,” Hyacinth said.

“You remember me, right?” the girl said.

“Yes,” he replied. He remembered people almost all the time now, and he absolutely remembered that girl with the blue dresses and the grape soda, he just got mixed up on what he was supposed to call her.

He had to not do that. That made her sad. He liked her. “You’re… you… You’re Maggie.”

“Yeah.” She smiled.

“Do you hafta have, uh… uh… upstairs?” He tried pointing.

“Lessons,” she said. “Yes.”

“It’s my birthday?” he said hopefully.

“I have Sun’s Days and bank holidays,” Maggie replied. “We can have lunch if it stays nice out. I’ll buy you a grape Pin-Min, okay?”

“Okay.” He looked down at his plate. There was still some… square pieces. He pushed one around, chasing the syrup.

“I’m not going back right now, Erik,” she said. “I’m not done eating pancakes yet. We never have pancakes. I didn’t know Milo could make pancakes. He eats cornflakes when there’s nobody here and he’s gone.” She took two more.

He smiled. “Okay.”

◈◈◈

He went back in because he needed his eyepatch for the dust and the wet and the cold. Hyacinth was going to make him a new eye, but she said he probably wouldn’t like it right away and it could wait until things were a little easier for him.

He went back in, also, because he got worried and he made excuses.

The glass was still… still…

Those are curtains, he told himself. C…

T? Curtains?

He wished he could spell! It would be so much easier if he could write it down. He could label things!

His patch was on the table. He held it. He’d have to put it on in the mirror. It was hard to do the… the strings.

“I had breakfast,” he said.

Sometimes there wasn’t an answer.

There was this time, but it took a little while, “Was it all right?”

“Yes. It tastes lots better. We had puh… pih… pillows.”

“…Okay.”

Erik wondered if he’d be happy if he said it was his birthday. He thought probably he wouldn’t. He thought probably he’d be sad because he could only have a little birthday.

“Do you want breakfast?” Erik said.

“I will in a little.”

He wouldn’t, but Hyacinth would come in later and make sure he had something, even if he didn’t want any pillows. She fed everyone else first because they didn’t say no.

Erik went through his pockets and found a folded drawing of a monster and a cat’s eye marble. It was a bug-eyed purple monster with hairy green toes and it appealed to his sense of aesthetics.

Maggie could read what it was and she told him but he didn’t remember. He used to read, and he could still tell the letters if he followed with a finger and went very slow, but he couldn’t hook them up. He couldn’t copy them down, either, even though he knew what they were. He just made lines.

Hyacinth said, It’s okay. Keep trying. She put it on the schedule. He didn’t like it very much. He wanted to read and write, but he didn’t like the part where he kept getting it wrong. His uncle didn’t like it either. He pretended it was okay, but you could tell it made him sad.

And sometimes it was too much sad, and he couldn’t come out of the bed.

Erik left the drawing on the table so he could come back and get it later.

◈◈◈

It continued sunny and clear, so Erik and Maggie were allowed out for lunch, though Erik did have to contend with a knit cap pulled over half his face and an admonishment from Hyacinth not to play in the snow.

That annoyed him. It wasn’t like he liked the snow. He remembered liking the snow, but cold things still hurt his head. He lived in fear of well-meaning snowballs from the neighbourhood.

There was a cart nearby that Maggie’s mother had approved of for lunches. It was available in fair weather year round. She was supposed to get an apple and milk and she was allowed to use her own judgment for the contents of the sandwich. She did this often enough that her mother trusted her with the money and rarely checked up on her anymore.

There was a storefront bodega in the exact opposite direction where they sold candy, and they were sitting at one of the tables inside with the results of two days’ lunch money combined.

“What are these ones?” he said.

“Licorice,” she said.

“Licorice.” He winced. “I don’t like it.”

“Really? You used to like it. Does it taste funny?”

“No, I just don’t like it.”

“I’ll take that bullet for you,” she said, gathering the black pieces.

“These are Sour Buttons,” he said.

“Yeah.”

“I like them. And these are Zings.”

“Yeah.”

He chewed thoughtfully. “These taste like red.”

“Do you really mean ‘red’?” She had one and considered it. “I guess they do.”

“Your… Your mouth is red,” he warned her.

“I’ll brush my teeth before I go back up,” she said. “Don’t forget your soda.”

He held the bottle up to the window, so the sun shone through. The man at the counter just gave him the soda, so Maggie didn’t have to buy it. Maybe he knew about the birthday. “I like the grape. Why did you get milk?”

“My conscience is bothering me,” she replied. “Do you still like blue raspberry?”

“Yes.”

She broke the sucker in half. The magic left a little curl of sweet smoke, but it wasn’t enough for anyone to notice. “Do you want stick or no stick? No, I hafta have the stick. I have gloves. Cin won’t mind if you’re sticky.”

He held the cracked piece in his hands and mouthed at the edge. “My uncle might mind.”

“He won’t notice.”

Erik sighed. “Yeah, I guess.”

“My daddy left you a present but he’s not sure if you’ll like it. He said I should use my judgment.”

“Can I see it?”

She had it tucked inside of her coat. It was a small, flat parcel wrapped in brown paper and string. “He had it all nice, there was foil and a bow, but he unwrapped it so I could see. I had to do it again.”

He undid the string and folded back the paper carefully, without tearing. It was good to have paper for things; he still liked to draw, even if he didn’t need it to remember as much.

The box was polished dark wood with a label. He didn’t try to read it, he just opened it.

Soldiers. Not the big ones with real uniforms, little ones with paint. They were lined up neatly in individual slots. Some standing at attention, some kneeling to fire. They had tall black hats and red jackets.

The four in the top row were riding horses.

“Oh,” he said.

“He thought you’d like them. He didn’t know.”

“Yeah.”

“We could blow up the ones with the horses,” she said. “I can do deconstructions. You wanna?”

He touched the fuzzy cloth substance on the inside of the case. “I think I won’t like empty places.”

“We could blow up all of them.”

“No, that’s mean.” It wasn’t their fault some of them had horses. “Are they lead soldiers? Can I keep them a long time?”

She frowned, then she quirked a half-smile, “They’re tin.”

“Oh. Like me.”

“Yeah. Daddy said it’s like a bad joke. He was just sick about it, but he didn’t have anything else and he had to go. You’re gonna get a really good present when he comes back. He’s gonna bring you an elephant or something.”

“A real one?” said Erik.

“No, I guess not, but I said he should.”

“I don’t know if elephants are safe.”

“If it’s not safe, we could eat it. They used to have elephants in the zoo, but they got eaten. Mom says you can eat anything with sauce.”

It occurred to him: “Your mom eats birds.”

“Pigeons.” She was grinning, proud of it.

“With sauce?”

“I don’t think she bothers when it’s just pigeons.”

“Will you eat pigeons?”

“I guess.” She turned her hands on the table and looked out at the sky. “If I ever get it right.”

Erik drained his soda and spun the bottle on the grooved wood. He liked the noise. “How come your mom doesn’t like the store?”

“They have magazines with pictures of naked ladies, and one time they sold me some cigarettes.” She picked up the ashtray on the table.

“Why?” he said.

“Wanted to see if they would,” she said. “Turns out they don’t care. Lots of kids smoke. I think Soup smokes.”

“Soup has a red bow tie.”

She nodded to that. She had been making some effort to reintroduce him to the neighbourhood but it was hard because he got embarrassed when he didn’t remember. It was worse when they didn’t know what had happened. She had to keep explaining him.

“Why is he Soup?” Erik said.

“It’s because he’s always hanging around soup kitchens. Cin thinks he doesn’t have anyone to take care of him. I think he just likes soup.”

“Which one is Cornflakes?”

“Cornflakes has blonde braids, but they hang down like this,” she put her hands at the side of her head, where her own braids seldom ventured, “and her dress is always dirty at the bottom because she picks things out of the gutter.”

“Some friends are called food,” he said, mystified.

She shrugged. “Just Soup and Cornflakes. Erik, eat faster, we gotta get back.”

“Mm-mm,” he said. He didn’t like to shake his head and it was starting to hurt. “I don’t want any more.”

Frowning, she considered the last few pieces. She could have eaten them, but she put them back in the bag. “Are you feeling okay?”

He answered sharply, “Yes.”

◈◈◈

He wasn’t, and the old headache had sunk its claws in by the time they got home. He was walking ahead of her, impatient, shielding his eye from the light of the sun. He tasted metal, and the candy was a twisted mass in his stomach. The cold was like a knife in his socket. It was loud.

He got things in pieces. Street. Tree. Yard. Stairs. Door. Hyacinth.

She looked creased and worried and she wasn’t wearing her goggles so she must’ve been waiting around. “Maggie, you left it a little late…”

“I know. I’m sorry. I took him to the store and we had candy. I shouldn’t’ve. Will it be okay?”

“I don’t know. Let’s see if we can get him into bed.”

“I hate it when you talk over me,” he said. “It’s like I’m not even here! I’m not stupid!”

Oh, no. He did think that but he didn’t mean to say it. He didn’t mean to say anything. It just came. He was so tired. He felt sick. He didn’t want to be talking.

“Why don’t you ever fix that hole in the roof? It gets cold in here. How can you run a boarding house when you can’t even keep a roof on the place?”

“Basement,” said Hyacinth. She picked him up under the arms like a sack of potatoes and carried him.

He cried out, “Don’t touch me, you baggage, that hurts!”

“I’m sorry,” said Maggie, trailing after, “I’m really, really sorry.”

“It’s all right. Just help me. Ow!”

He had kicked her. He didn’t mean to do that either. His shoe left a wet print on the front of her dress.

They were going to put him to bed. He didn’t want it. He did want it, he was so tired, but something in him didn’t want it. It was mad and it wanted to talk and it kicked people. He didn’t like it. It scared him how he couldn’t say “no,” or “wait,” or “stop.” It was like falling.

But it hurt less. When the headache clamped down and things started to happen, just letting them happen made it hurt less. He always kept talking about how much it hurt, and he knew there was pain, but it was someplace else. Or he was someplace else.

A little room with less pain, and he could only listen and look out the windows.

“I don’t want those soldiers,” he was saying. “They’re stupid. Your father must be an idiot for thinking I’d ever like them. He should’ve thrown them away!”

Oh, no, don’t say that. I only don’t like them a little bit. I don’t want them thrown away.

He hoped Maggie wouldn’t do that. He hoped she knew he didn’t mean it. This just happened when he was tired.

It hadn’t happened in days. It probably would’ve been all right if they didn’t go get candy. There were times for things. It helped because sometimes he got lost and he could remember better if the same thing always came next. After lunch came bed. After sneaking out to get candy came… nothing, apparently.

He forgot about bed and he got too tired. It was okay when he forgot some things, if he didn’t get his shirt buttoned or comb his hair, but when he needed to sleep, he really really really needed to sleep.

Now he wouldn’t sleep until he exhausted himself, and he would sleep too long, and he wouldn’t be sleepy when it was time for bed again, and all day tomorrow would be pain and no words.

“Let me go!” he was saying. They were trying to get his buttons undone and he kept pushing them away. “I want to leave here! I hate this place!”

It was getting worse. He didn’t think that hardly at all.

“You’re not going anywhere,” Hyacinth said. “Why don’t you just leave him alone?”

Silence, for a little while. He’d stopped struggling too. Then, with something like cunning, “Give me a cigarette.”

“Not happening,” said Hyacinth.

Now Maggie, who was holding both his ankles to prevent him from kicking: “Cin? Do you think we’ll have to hold him down the whole time?”

Now Hyacinth, who was looking past him at the flimsy wooden cot beneath: “I just hope we don’t have to tie him.”

“Is he getting worse?”

“No, I actually think he’s getting better. The pain’s less, that’s what this is.”

“But then shouldn’t they go away?”

“I don’t know. I don’t know how any of this works. Mordecai might, but he’s just been useless.”

That offended him. My uncle is not useless, he’s just sad. But, of course, he couldn’t say it.

“I want to have a bowl of cereal,” he said. “I’ll stay and I’ll let him sleep.”

“Cin…” said Maggie.

“No deals!” said Hyacinth.

“You’re awful!” he cried.

“You said Cousin Violet was nice,” said Maggie.

“Sometimes Cousin Violet is nice, but she doesn’t give a damn about him. None of them do. This way, they can only make him talk and walk him around. I don’t know what they’d do if we said they could come in. Some of them can set things on fire, Maggie.”

“I can do that and you’re not worried about me,” Maggie said.

“Give me a cigarette or I’ll burn your whole family alive,” he said.

“Okay, nevermind,” Maggie said.

“If you could do that, you would have weeks ago,” Hyacinth told him, whoever he was.

“I want a cigarette!”

And now it was all “I want.” It always came down to “I want,” and so many things he didn’t want. Some things he didn’t even know! I want strawberry jam and pancakes! I want to go dancing! I want a chocolate soda! I want whisky and ginger ale! I want to read poetry! I want to go to the movies! I want to make love! I want to kill! He wasn’t even sure what he was saying or what was just near.

I want to be quiet and go to sleep, he thought miserably.

They don’t have to give you what you want, kid! You’re damaged! This, near but not said, with something like glee.

The radio.

I hate you. Don’t ever talk to me.

He withdrew. He had been pushed aside, but now he withdrew, so he couldn’t tell the voices anymore and they just happened.

You’re gonna love me, kid.

That was very near, almost in the same room, and it scared the hell out of him.

You give it a few years. You’re gonna love me, and you’re gonna need me.

I think I won’t remember that part, he told himself, shuddering. I think I’ll wake up and I won’t remember that part at all.

◈◈◈

“Erik?”

“Ohh.” He shivered and pressed his hands to his eyes… To, to his eye and the empty. The heel of his palm went inside a little.

“I know, honey. Do you think you can manage some dinner? I’ll bring it down here if you like. You don’t have to talk or see people.”

“Dinner.” He took his hands down and stared helplessly. There was… There was this person he knew.

I know you. I can’t say you. You wear glass… globe… round yellow glass and you have yellow… head.

That was all wrong and he knew it too.

“Here, honey. Drink this and try to wake up a little. I’d like you to eat. I’m going to try you, even if you can’t talk to me right now.”

He held the… warm. It was warm. He lifted and drank.

“It’s juice,” he said.

She nodded.

He frowned. “Don’t. It’s wrong.”

“I’m sorry, but you’re really close.”

“Don’t say it.”

“I won’t.”

He stared into the cup. He drank again. “It’s tea.”

“Yes.”

He sighed. He drank again. “Is it… same day?”

She shook her head as she spoke, “It’s still your birthday but you don’t have to have any more birthday stuff if you don’t want it.”

“Will… sing?”

“Do you want them to?”

He shook his head. “All voices. No.” He winced. He remembered… some things he didn’t like. “I’m all voices. I’m sorry.”

“No, Erik. I know you’re not understanding me very well right now, and maybe you won’t remember, but I’m going to keep telling you so you do. That isn’t you, when that happens. There are things you can’t see, and they can make you talk, because of how you are. But it’s not you.”

“Like me,” he protested.

“They’re not even a little bit like you. I can tell right away.”

He didn’t mean it quite that way, but he wasn’t sure how he meant it, and it felt good to hear her say that. “Are the soldiers?”

“Your soldiers are fine.” She smiled. “But Maggie put them up where you couldn’t find them in case you got away.”

“Say ‘thank you’ to Melly.”

“You can say that.”

“I can’t talk.”

She grew stern, “Yes you can, and don’t you dare stop trying.”

He was too tired to argue and he didn’t like it when she talked mad. “Okay.”

“Do you want to come up for dinner?” she asked him gently.

“Yes, but no more birthday.”

“That’s fine.” She helped him up and there were… up… walk… stairs. She stopped in the middle and she said, “Oh, shit, but Milo brought home cupcakes.”

“Pancakes are okay.”

“Cupcakes, honey.”

He meant cupcakes. He meant small round things with paper and frosting, anyway. What did he say? “Cupcakes are okay.”

“Okay, but you tell me if anything isn’t okay and I’ll explain to everyone.”

“Yes.”

◈◈◈

The pink woman was sweeping towards him like a big, scary sheet and she had red and she smelled and she was already talking.

He cringed from her and knocked back into the yellow woman’s legs.

She put her arms around him and he turned his face against her dress, which wasn’t yellow but he couldn’t say what it was. “Please, Ann, quietly. He does still like you, it’s just been almost all Milo the past few weeks and he’s too scared to remember you when you come at him like a freight train.”

“Oh, I’m so sorry,” said the woman in pink, with both hands over her red mouth. She was a little easier that way. She had lots of red hair. She smelled like flowers. It wasn’t bad, it was just… lots. “Hello, Erik. I’m sorry. It’s only me. Happy birthday.”

“We’re not having any more birthday tonight, Ann. No, but he did say the cupcakes were all right.”

The woman in pink was still frowning with her hands up. “But what about a present?”

“I don’t know, but will you let me get some dinner into him first? Please?”

The pink woman stepped aside. “Oh, I’m sorry. I am sorry. He’s just been having such a hard time of things and I wanted him to have something he likes. Oh, he looks so dreadfully unhappy. I’m so sorry.”

“What he likes right now is for things to stay the same and be easy. We can have more birthday when he feels better, Ann. I promise.”

“Oh, no, Cin! Only if he wants it! Don’t promise me!”

“Quieter,” the yellow woman said tightly.

The pink woman spoke through her hands again, “I’m sorry, Erik.”

He hugged his own shoulders and tried to be brave. She wasn’t scary. She was just lots. He knew she was nice, and something about crayons, but he didn’t know how to talk to her. He didn’t know if she was even going to give him a moment to say something. He half-wished the voices would come back. They talked faster.

“Pink,” he said faintly.

She nodded with her hands over her mouth. “Mm-hm.”

That gave him a little space to think. “Pink is… Tiw’s Day.”

“Yes, dear. That’s just right. You said that very well.”

“You’re…” Oh, he knew it. He did know it! He just heard it. “Auntie Milo.”

She smiled. It was red and white and big, but very happy. “Yes, dear. Sometimes I’m Auntie Milo and sometimes I’m Uncle Ann. And if it doesn’t always match up just right, that’s all right. We don’t mind.”

“Milo doesn’t talk.” He remembered from this morning.

“Yes, you’re right.” She covered her mouth again. “Do you like that better?”

He shook his head. “It’s different. Does he like it?”

“No. It’s awful. He hates every minute of it. He wanted to say this morning that it’s okay to call him Ann, even if it’s not just right, but he couldn’t and he was just miserable about it all day.”

She knelt down and put her arms around him. She was soft and careful and felt good. “Don’t ever stop talking, Erik, not even if you want to. It’s better to have the wrong words than none at all. Promise me, okay?”

“Okay,” he said. “Auntie Ann?”

“Yes, dear?”

“My present isn’t horses, is it?”

“Oh, good heavens, no!” she cried.

“I’d like it.”

“Right now?”

“Yes.”

“I have it.” She tucked her fingers down the front of her dress and dropped him a wink. “This makes an excellent pocket, Erik. I keep tissues too.”

“You keep socks,” Hyacinth said.

“You’re a cruel woman, Hyacinth,” Ann said. She presented a flat square box wrapped in red tissue. “Here, darling. Milo finished it days ago, but someone said you weren’t ready to mind your own hours yet. I think that’s ridiculous. I think you’d like to have it even if you don’t always remember what it’s for. And you badly want accessorizing, Erik.”

He only half-heard her. He was trying to do the tissue without tearing it, but he couldn’t. He gave in and pulled a big, ragged rip right down the middle of the box that was intensely satisfying. The lid was tight and he had to wiggle it to get it up. Inside was a square of wispy white cotton and a silver pocket watch.

“And if it breaks, that’s Milo’s fault for using a cheap watch. And if Cin wants the metal, then we’ll save out the face. That’s just pasteboard and a little magic, but it’s the only special bit.”

The watch front was glass only, no cover to fiddle with. The face of it was white with hands but no numbers.

Here was a little pencil sketch of a bed. A circle was described above it, an arrow showed the direction, and a tiny notation indicated two-hundred-and-seventy degrees. When he brushed the glass above it with his fingertip, it got bigger and it moved. The corner of the blanket followed the circle and folded open.

Here was an open shirt with a very complicated arrow and many little notations. When touched, it did up its own buttons

Here was a closed eye with lashes and another arrow indicating upward motion at ninety degrees. The eye opened. He giggled at it. It wasn’t a real eye, it was a metal one, like Hyacinth promised him.

Milo did drawings like these for magic things, and he had done a lot of them about an eye. This part goes here and does exactly this. There was a word for that, but it was big and difficult and he didn’t really mind what it was. He just liked the drawings.

Here was a sandwich that disappeared in precise little bites. Here was a fork circumscribing three-hundred-and-sixty degrees to roll up spaghetti. He liked spaghetti for dinner and a sandwich for lunch!

“Will it be different if I don’t have spaghetti?” he asked.

“No,” said Ann. “Would you like that better? Milo could…”

He was smiling, wide and content. “No, I like it always the same. I remember better like that. What about breakfast?”

“AM,” Ann said. “Here, I’ll show you.” She pulled up the watch stem and rolled the hands forward.

Everything changed. Now the bed was here and the eye was here, and here was an egg in an egg cup where the top cracked and came off.

“I’m glad,” he said. “But I don’t like seeing it change. I feel scrambled like I’m out of the bedroom and it’s bright.”

“Oh.” Ann turned the watch towards her so he didn’t have to see it while she reset the time. “Well, you won’t be awake when it happens at night, but you might see it during the day. I think maybe Milo can fix it so that it happens very slowly. Is that any better?”

“It’s maybe, but I don’t want to give it back yet,” he said. He held out his hand for the watch, and Ann obligingly dropped it back in. “Thank you. I love it. It’s better than soldiers, but don’t tell Maggie.”

“Oh, never a word!” Ann said, beaming. She mimed locking her mouth and throwing away the key.

“Titanium wouldn’t do it,” Hyacinth said. “Please can there be dinner now? I only brought him up here for dinner.”

Ann turned up her nose. “He needed that, Cin. He’s much better when he has something he likes to talk about.”

Erik flushed (with his colour that just turned him a little darker) and pressed a hand to his mouth. Did he work that way now? He did, didn’t he? Oh, everyone knew more things about him than he knew about himself.

“I know he needed it,” Hyacinth said, “that’s why I’m not yelling at you. He also needs dinner. Stop helping him!”

“I shall never stop helping you, Erik,” Ann said, not impeding but nevertheless following him up quite closely. “Not even when it’s not me. And tomorrow morning, Milo will stay and show you how to wear your new watch. It looks quite smart if you have a vest like your Uncle Mordecai, but it works perfectly well with trousers too…”

He nodded, but he wasn’t really listening. He was starting to think you didn’t really have to listen to Ann, not every word. You could check in occasionally and see if she was still on about the same thing, and then it wasn’t too much.

She was saying things would be okay and she’d fix him. He’d like that. He could use fixing.

Dinner wasn’t spaghetti, but it was noodles. It was one of those noodles-in-the-box that Auntie Hyacinth liked to do. You could have them like soup or in the oven. These were oven noodles.

Maggie’s mom was there. She had a full plate of noodles and she was sitting with her hands folded behind it and waiting for him with grim politeness.

He tried to eat fast.

Maggie was there, too, looking a little bit sad, and Ann and Hyacinth.

Uncle Mordecai didn’t come.

“I’m not allowed lunch out for a month,” Magnificent whispered aside. “But she also says I’m brave and resourceful, so I dunno.”

“I think you are those things,” he said.

“Thanks. Your soldiers are on top of the hall wardrobe. You’ll hafta stand on a chair.”

“Thanks. Look what Milo gave me.”

“Erik, remember dinner,” said Hyacinth.

“Yes. Sorry.”

After, there was a cupcake for everyone and one extra. They were white with pink frosting and a cherry. The cherries had bled red marks into the pink frosting around them. There were no candles and no singing, which was just right.

He had to have a little bit more cupcake than he wanted because Ann said they were a day old and it wouldn’t be very nice if he saved it for tomorrow, but that was okay. “Can my uncle have the other one?” he asked. “Does anyone else want it tonight?”

“I am not fond of cupcakes,” the General said. She had eaten hers and folded the paper wrapper, but perhaps it was more duty than desire.

“I’ve had enough sweets, thank you,” Magnificent said, squirming.

“Erik, of course he can have it,” said Hyacinth, “if he wants it. You can take it with you when you go back to bed.” She knew damn well Mordecai wouldn’t eat anything if you just told him about it.

“I’d like to now,” said Erik. He wasn’t tired, not tired, but he was tired of people. Tired of lots of people, anyway.

He considered the pictures on the dial. “I don’t have to undo my buttons.” They’d let him eat in his nightshirt, since he was only going to be up for a little bit. “I have to brush my teeth,” he decided.

He needed water from the kitchen.

They filled a great big stone… or grey… bucket. Flowerbucket. There wasn’t any metal in the sinks, or any metal to get water to the sinks, so everything went into the bucket. The bucket had lions on it. There were more buckets like that in Strawberry Square and he thought probably they stole it.

He scooped up a glass. It was a jelly-glass with a purple bunch of grapes on it. All the grapes had little smiles. That was his glass. It was in the picture.

Hyacinth was blinking. She’d been about to help him. “Do you… need me… to help you?”

“Yes, because I’ll forget the cupcake.” He held up the watch. “It’s not here.”

“Oh. Right.”

She went with him to the downstairs bath. You could have toothbrushes on the sink, but you couldn’t really use the sink. Everything would just go on the floor. You had to use the glass and dump it outside. She reminded him about the cupcake on the way back to the bedroom.

Ann was doing dishes in the kitchen. Maggie and the General had already left.

He hugged Ann and put his face against her pink dress. It was soft and crinkly. “Thank you for everything birthday,” he said.

“Oh, darling, you’re very welcome. Good luck with that.”

Erik clutched the cardboard box against his chest. “Yeah.”

◈◈◈

He said goodnight to Hyacinth outside the door. If Uncle Mordecai didn’t want a cupcake, Hyacinth would be really mad at him. It was better to not have that. He didn’t pull open the door until she went away.

Okay, he told himself. He sighed and went in.

He had to leave the door open a little because it was dark inside. The big window let in a lot of light from outside, but the curtains were drawn.

Uncle Mordecai wouldn’t open the curtains. If someone else opened them, he would close them. He came out sometimes, but he didn’t like it. He’d sit in the kitchen and stare at a bowl of cereal, or a sandwich, or a soup. He didn’t leave the house. He didn’t have anything to play, no way to make money, and nothing he wanted to do. He only sort of got dressed, pants and a shirt, sometimes not even shoes.

Erik didn’t know if he’d been out at all today. He’d kind of lost track of things after lunch.

It was bad if he didn’t come out at all. It was worse if he didn’t come out at all.

The green child sat cross-legged beside the larger bed and held the limp cardboard box in his lap. He felt the cupcake thump over and he put a hand in blindly and righted it. He held it more carefully. He couldn’t see anyone moving in the bed, just blankets. Uncle Mordecai had a lot of blankets because he’d get sick when he got cold.

“Uncle? Are you awake?”

Some movement. A sigh. “Yes.”

“Did you have any dinner?”

“Did you?”

“Yes. It was noodles.”

“Good.”

Silence, for too long. “I,” said Erik.

“Was there any cake?” said Mordecai.

“Um. Yes. Little cakes. Cupcakes.”

With desperation, “What about presents?”

“Yes. Maggie bought me candy, and some soldiers, and Milo gave me a… a… um… Schematics!”

Mordecai processed that as best as he was able. “It’s not a lot,” he said.

“I didn’t want a lot,” Erik replied. “I don’t like a lot right now. Hyacinth says I can have more when I’m better.”

Weakly, “Oh. Yes.” And now, with difficulty, “I’m really sorry.”

“No,” said Erik. He set the box aside and sat forward. “Why?”

“I didn’t get you anything. I’m sorry. I didn’t even… I didn’t anything.” He was crying. It hurt to hear.

Erik swallowed and hugged his own shoulders. “Please don’t, okay? Please. It’s okay. I had a good birthday. I didn’t want anything. I thought you didn’t remember.”

Mordecai sat up and flung down the blankets. “Of course I remembered! You thought I didn’t remember?” For a moment he couldn’t even cry, then he did and he couldn’t stop.

Erik crawled into the bed and into his lap. He hugged, and Mordecai hugged him back, shaking.

“I thought you’d be less sad if you didn’t remember,” Erik said. “It’s how come I didn’t say anything.”

“I’m sorry. I’m sorry it’s like this. I’m sorry I ruin everything.”

“Stop.” Erik swiped his arm across his face. He put his hand over his uncle’s mouth. “Don’t say all that. It’s wrong. It’s not you talking.”

The red man sighed. He wiped his own eyes. “You’re right. I’m sorry.”

“Dooon’t,” Erik said, twisting.

“I won’t. No. I won’t.” Mordecai hugged him again. “I need tissue. Do you need tissue?”

Erik nodded. He dug his fist against his one eye.

Mordecai reached across the bed and snagged the box. He frequently needed tissue. It muffled the cough and then he could throw them away, and no one would notice the occasional tinge of red.

He wiped Erik’s face first, taking special care around the empty metal socket, which should not be wet. “That’s better. Is that better?”

Another nod.

“Have I hurt you?”

Shake of the head.

Not true, thought Mordecai. He wiped his eyes and nose, then he had to cough for a little.

Erik brushed his cheek with a warm hand. “Okay?”

“Yes.” He coughed again, “Yes,” and then not any more. They held each other. He rocked the child.

“I brought you a cupcake,” Erik said. “Is it okay?”

He shivered. “Yes.”

“You don’t have to have it.”

“No. I’d like it.” He swallowed. “It’s your birthday.”

“It’s here.” Erik crept to the edge of the bed and found the box. “It’s pink. It’s hard to see.”

“Thank you.” He peeled down the paper. “What’s this?”

“Cherry.”

“Want it?”

“I brushed my teeth.”

He ate it and pulled out the stem, then he had a bite of cake. “It’s good.” He was crying again.

“Uncle…”

“No. It’s just hard to stop.” He finished, then he dried his eyes. “Happy birthday, Erik.”

“Happy birthday, Uncle Mordecai.”

That was wrong, but no more so than anything else. Mordecai just hugged him again.