It was lunchtime, and the ice cream parlour was buzzing. They didn’t sell chips or sandwiches, but ice cream was part of a balanced diet in Strawberryfield, where poverty begat a Live-for-Today sort of attitude: I can’t afford rent. What am I going to do, save up for a nice sofa? Buy a pot roast to cook on that stove I don’t have? Gimme a root beer float with two scoops of vanilla and if I have anything left I’m going to the pub!

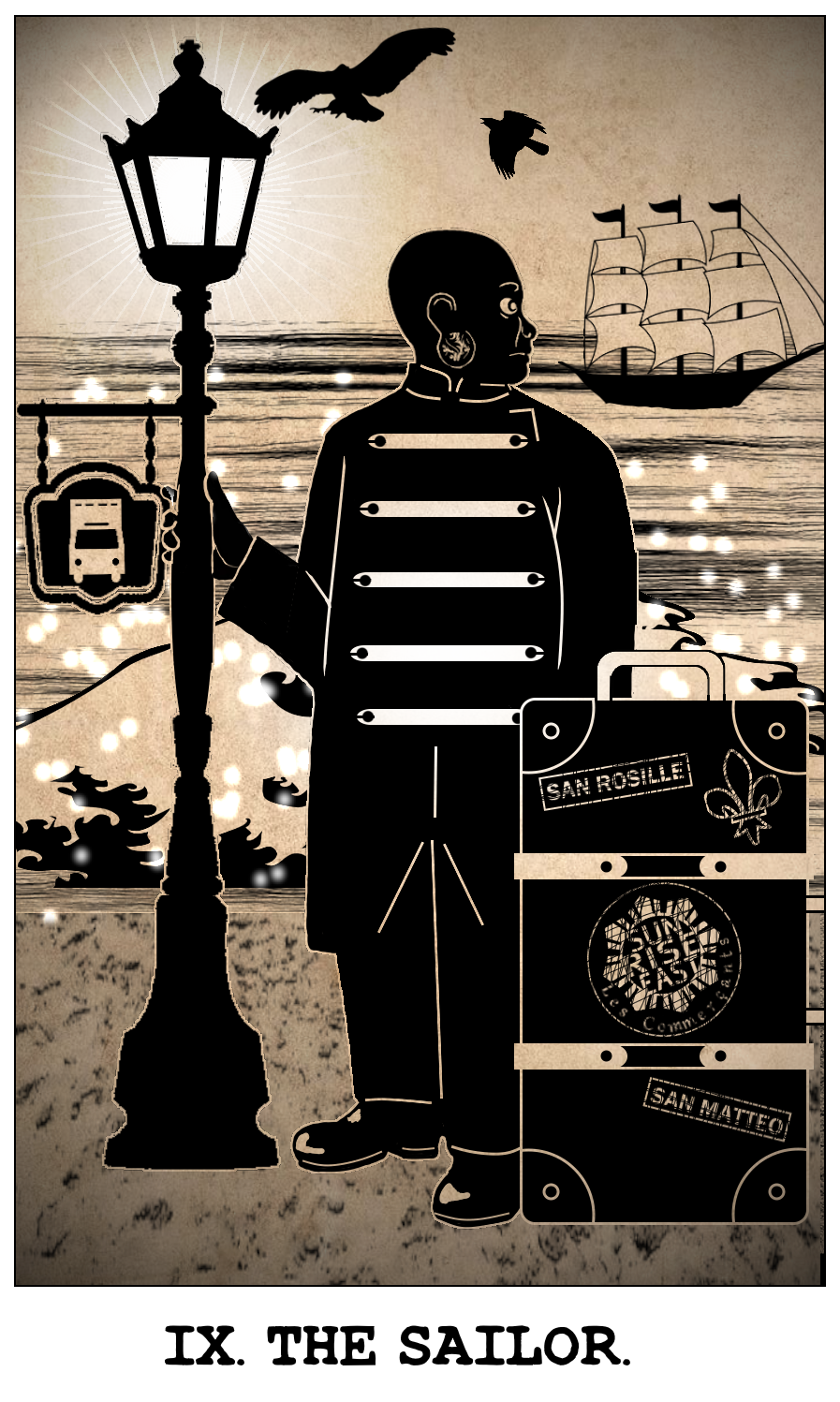

Maggie and Sanaam had been allowed to depart unaccompanied with a few apologies and a promise to bring back more ice cream for the house. It was Sanaam’s last full day at home and even Erik knew something was up.

Maggie considered the chalkboard in the window with the flavours on it. “And what kind of ice cream goes well with serious conversation, Daddy?”

“Any kind you like,” Sanaam said.

She got a banana split. He ordered a chocolate malted, with the understanding that he’d also be partaking of whatever banana split Maggie didn’t have room for.

They edged through the clustered tables and chairs and found a free spot up against a wall — where Sanaam’s broad shoulders and broad everything else would be less of a hindrance to people trying to get by. The dishes sat unevenly on the mesh table-top and Sanaam pulled the table up so near that it dented his stomach. Maggie had a perfunctory bite of chopped nuts and whipped cream.

“So I’m taking Zippy out this time,” Sanaam said.

“I can say ‘Zephyr,’ Dad,” Maggie said.

“I like Zippy,” Sanaam said haughtily. “I’m just not allowed to paint it on the side of the boat ’cos it’s bad luck to change the names.”

She already knew what he was going to ask, and she already knew what she was going to say, but they had to dance around it like this. They didn’t like to hurt each other, but sometimes it frustrated her having to do it this way, like ripping off a bandage one hair at a time.

“I’m going to swing by Grammie and Grandpa’s house,” Sanaam said. “We’ll have Yule.” He smiled and shrugged. “Maybe not on Yule, but every day’s a holiday when I show up.”

“Yeah,” Maggie said.

“It’s been a couple years, you know. They miss you. All they get are photos. We can stay in your old room,” it was his old room, too, “and have shaved ice and coconut, and real beaches where you can see through the water…”

Maggie lifted a hand. “Yeah, I know.”

She did not need a sales pitch, the islands were awesome. Palm trees and warm breezes. White sand and bare feet. Freedom. Her mother might not even want to come. And everyone there was like family. All smiles and laughter and nicknames — she was willing to put up with the nicknames. There would be a party with a pig in a pit, pure white fish wrapped in banana leaves with bacon fat, roasted sweet potatoes, music and dancing.

She missed her grandparents too. Every time she went back, they seemed older. It wasn’t like when she used to live there and everything stayed the same. Always sunny and warm. Always fun and friends. Always the same faces. Now that she left and came back, they kept changing things on her. A house would be gone. A person would be gone, or there would be new people who didn’t know her. And the wrinkles kept getting deeper, like someone was carving pieces out of mahogany wood.

Last time, she’d seen her grandmother’s hair was starting to powder white under the headscarf. It frightened her.

They just keep going on without me…

And she missed the boat. The Zephyr was Daddy’s boat during the war, before she got sold to a trading company and he went with her, and Maggie had lived on that boat sometimes so she especially missed the Zephyr.

I’m sorry I blew a hole in you that one time, Zippy. Mom said I couldn’t take the cat with me, you know how it is.

But she didn’t just miss the tiny nest-like rooms and the familiar layout and the plank next to the headboard where she’d carved her name, it was all the associated boat stuff. Not just being on the Zephyr, being on any boat. The wind and the birds, the creaking timbers. The roll of the ocean beneath, or the subtle vibration in every fibre when the magic drive kicked in.

(Okay, that was only some boats, like the repurposed supply ships Sunrise East Trading Company bought, so they could be fast. Zippy, indeed.)

Even the smells, which were really not all that nice. Damp hemp rope and salt, grease and oil and sweat. That industrial soap they scrubbed the decks with.

Oh, hell, and the conveniences!

When she was little, she used to be terrified of that creepy marine toilet, like a squid tentacle was going to snake out of it and grab her. Daddy, check it first. Check it. Now? The damn thing flushed! And she didn’t have to jimmy a lock for the privilege.

There were light switches on boats. You could turn on a tap and get water! Usually. Unless there was something seriously wrong and the tanks were low. Carpeting. There was carpeting on the boat. Metal things! Nails. Knives. Hinges and latches. Tableware that didn’t get all bent out of shape in the peanut butter jar. Like some kind of palace!

Her dad didn’t need to sell her on the island or the boat.

But it didn’t really matter.

“It’s just, you know,” she said. He did know, but she had to say something. “Lucy just got here, it’s her first Yule. And it’s Calliope’s first Yule with us too. And last year… You know, last year was really awful. And right now, there’s still this thing with Milo and Calliope, what if they need my help with something?”

Sanaam put up a hand and stopped her. He frowned and shook his head. “Now I can understand wanting to stay in San Rosille and play with the new baby, but that thing with Milo and Calliope is not your responsibility, Maggie. I daresay at ten years old there is not all that much you can do about it, even with magic. If you contrive to trap them in an elevator or make them team up to fight alien robots like a soap opera or a serial, you’re just as liable to break them apart as force them together…”

Maggie snickered. “You sound like you’ve put some thought into this, Dad…”

“But the bottom line is that they’re both grown adults and they made this mess, and they’re the ones to clean it up,” Sanaam went on sternly. “I don’t want you turning down a fun time and a… a childhood out of some misguided sense of moral obligation. There is always going to be something going on here. Milo and Calliope being upset is an order of magnitude below what happened to Erik. Otherwise, I wouldn’t be asking at all.”

Maggie turned away. The poster on the pink-striped wall was a butterscotch sundae. It was faded and hard to tell if the image was a still or a painting, but butterscotch syrup had been drizzled around the inside of the glass before the ice cream had been applied — attention to detail Calliope would have admired.

Maggie thought it looked like someone had taken a whiz all over everything, but that was just her frame of mind. She wasn’t even enjoying the real, delicious ice cream in front of her.

“No. It’s the same,” she said. “To me, it’s the same. Milo and Calliope wanted to leave, and if we didn’t catch them, they might’ve. If Calliope left, she’d go back to Ansalem and her parents and we might get a postcard but she’s not gonna do six hours on a train to come visit, not with a baby to take care of. And if Milo goes, we’re never gonna see him again, you know how he is. I don’t think even Ann could drag him back.”

“Maggie, I thought you were old enough to understand that snuffing out a candle is not the same thing as taking it into another room where you can’t see it!” Sanaam said.

“It’s still dark from where I’m sitting, Dad!” Maggie said. She sighed and sat back, arms folded across her chest. “Mordecai gets it.”

“I’m sorry, why were you talking to the guy who lives in Room 102 about life-altering shit?” Sanaam said.

Maggie slapped the flat of her palm on the edge of the table, rattling the ice cream. “You weren’t here when it happened! What do you want me to do, hold everything in until I get some kind of complex? You want me to be Mom?”

Sanaam pushed back from the table and put his head in his hands. I want you to need me for something, Maggie, he thought. I don’t want you to build a father out of stuff we’ve got lying around the house. I want you to need me.

“I’m sorry I’m not here more,” he said softly.

“Dad…” Maggie shook her head. She reached across the table but she couldn’t get to him from where she was. “I’m used to that.”

“Well, maybe I’m not.”

“Yeah, you are,” she said. “You just don’t like it.” She smiled and shrugged. “So we’re the same.”

Sanaam shook his head. No, Mag-Pirate, we’re not.

He never could decide, that was his problem. He got bored, and he got tired, and he started missing people again, people and things. No matter where he was.

Of course, when he was Maggie’s age, he didn’t know any better. He just wanted more. More than soft sand and warm water, dunes and unpaved roads that he walked barefoot. Palm trees to climb that just went straight up and down like a one lane highway, no exit. Nothing faster than a pushcart, and then only if you dragged it up that one hill. (Or got very desperate and hauled it up to the roof of the house…)

It had been like living his life wrapped in cotton batting. I’m still in my original packaging! Let me out! I want scratches and dents! He did manage some scratches and dents, quite a few, but it still wasn’t enough.

He read newspapers and magazines, cut out pictures and pasted them to the walls of his bedroom, mail-ordered models and pamphlets and finally, after a lot of begging, a full set of encyclopedias (which his wife had later dismissed as hopelessly out of date for Maggie’s education. So much for “the only reference you’ll ever need”!). I wanna drive cars! I wanna fly airships! I wanna fight battles! And then I’m going to the moon!

Aquila, actually. He had intended to go to Aquila. The big one. I’m going to Aquila, Mom! I want to see the big red dot!

Just be home in time for dinner, Sanaam.

I can’t, Mom! It’s three-hundred-and-sixty-five-million miles away!

But given that he lived on a tiny island in the South Seas, visiting the moon or Aquila or even a movie theatre first required that he get on a boat. Which he had managed to do at the age of sixteen — with pay!

He did rather well on boats. They didn’t quite satisfy his need for speed, not until the Zephyr, but they supplied change and challenge and adventure. He was a natural at climbing and hauling and enduring, as needed. When men with twice the experience were leaning over the rail and doing the tandem puke-and-pray, he’d be up in the rigging, laughing and anticipating every swell. Get down here, Sadiq! Goddammit! There is something seriously wrong with that boy.

Yeah. Obviously. But if it had only been a lack of common sense, he would’ve angled out of the orbit of his little planet and never looked back. Instead, as soon as he was getting his adventure itch nice and scratched, he felt a pull. There was a secondary emptiness, which gradually grew in importance until he could barely look at the damn ocean.

Gravity had kicked in. He missed home. Familiar faces, familiar places. Real food, not weird stuff out of cans, or from grimy, loud countries where the people were all different colours and he couldn’t even read the menus half the time. Warm, clear oceans that didn’t try to kill you, usually. Peace and quiet! Nothing louder than a kid with a bicycle and a playing card in the spokes. That soft, safe feeling of being packed in cotton batting, not dangling out of some guy’s pocket on a bus at rush hour.

When his time was up, and his voyage was through, and he stepped off on the simple pier and met his parents and family with a duffle bag and a crate full of souvenirs, he swore he was done. That’s it. No more adventure for me. I’ve learned to appreciate what I have. I’ll just get a nice job serving drinks at the Marselline Consulate and settle down.

And he was so very happy.

And then he was so very bored. And he missed the boat. And the friends he had made on the boat. And the constant motion. And waking up every morning with a new thing to see outside, and a new place to go.

And then he was fucking well screwed, wasn’t he? It was like he was piloting a bicycle with two panniers, but he could only fill one at a time. He was always lopsided and compensating for something.

Every time he made a new friend or found some new awesome place or tried some new awesome food, he had a new hole that needed filling. Oh, man, I miss Bill. Oh, man, I wonder what Roma is like in the spring. Oh, man, I could go for some glass noodles right now. Glass noodles for breakfast and a hamburger for lunch and whitefish wrapped in banana leaves for dinner.

And, oh, look at that. While you’ve been bouncing around like a pinball your daughter has turned ten years old and is going to other people for dad stuff. Where does the time go?

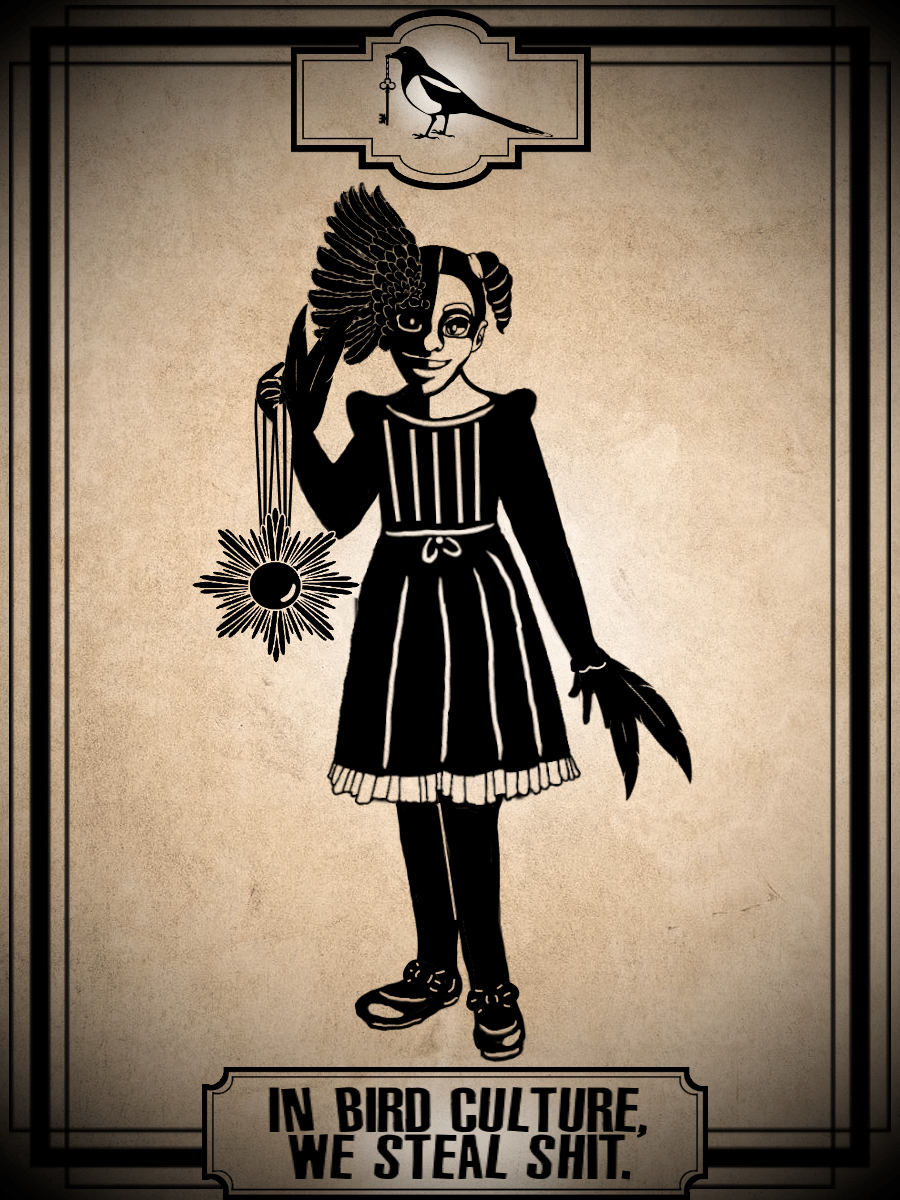

Maggie had picked up his crazy-gene (Maggie-Come-Down was her real nickname. He had to start calling her “Mag-Pirate” to fool her. That was psychology.) but not the ambivalence one. There was a hole in her that wanted the island and family and fun, and it smarted, but at no point did it put the key in the ignition and drive her. Yeah, I’d like to go back. Maybe later…

He thought — and he didn’t like to say it because that might make it true when it wasn’t yet — that she had chosen her place where she belonged, and everywhere else was just visiting. If she needed something from him, it was going to be love and support and that stuff he couldn’t physically do most of the time — not a ride and a guidebook to follow him around the world. They would visit each other, but her home was San Rosille, and his was… noplace at all.

Magpies nest, don’t they? I suppose they need someplace to keep all the things they steal. Birds nest, all of them do.

He was no bird, not even a seabird. He was a swimming thing that never stopped moving. Not a shark, too unfriendly. Maybe a lobster, like in Calliope’s room. No, a crab. A hermit crab, always outgrowing his shell.

Hey, did I tell you the one about the crab who fell in love with an eagle? They made each other very unhappy and were always apart! Ha-ha.

He reached into his back pocket and drew out the cheap metal compass with the glass front. He always kept it on him, and kept it hidden, when he was in the house on Violena. He didn’t want Hyacinth to steal it from him. He sort of hoped she’d forgotten about it, but he was too sensible to really believe that. He just had to pray there wouldn’t be an emergency dire enough for her to whack him over the head and mug him.

He watched the needle spin. It didn’t do that on the island, or on the boat. Or eating glass noodles at a street stall in Xin. He’d checked.

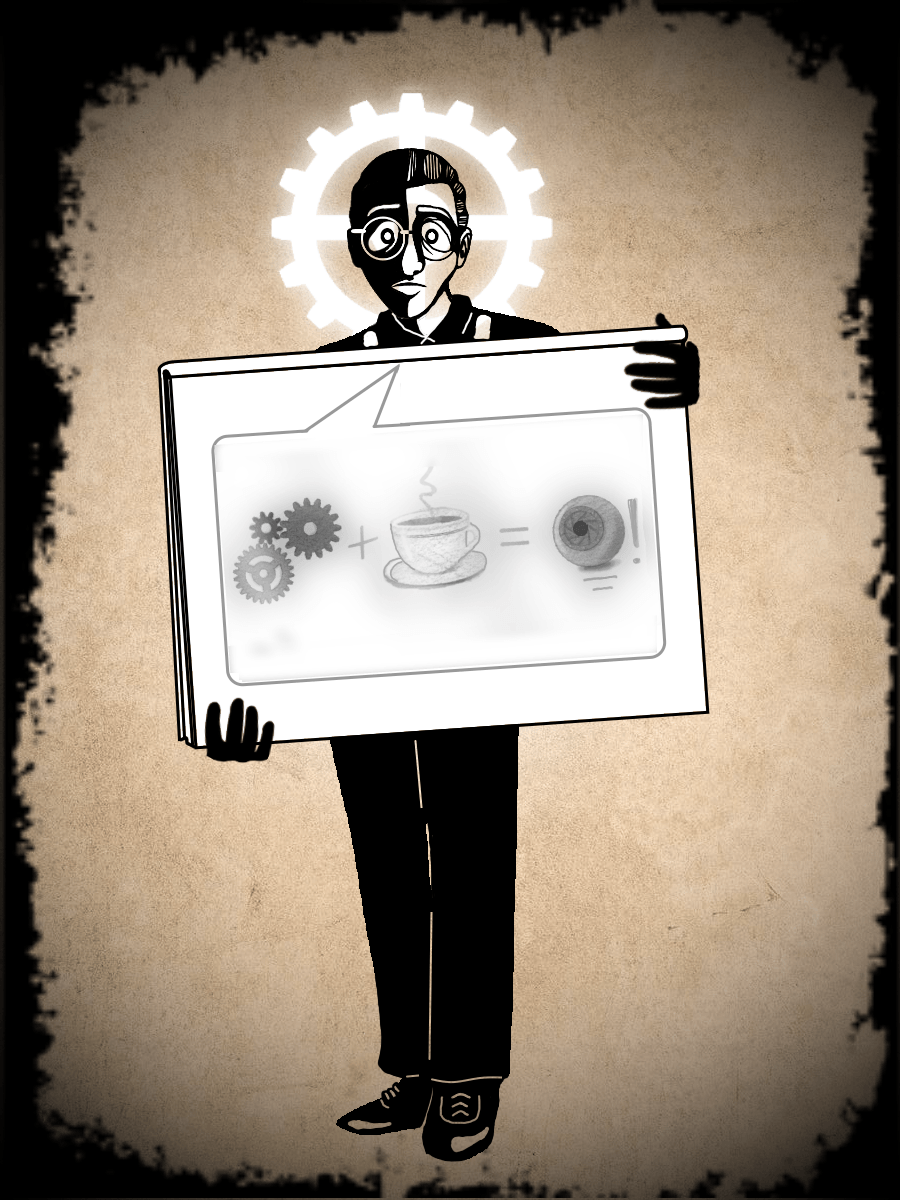

Maggie knelt in the seat of her chair and leaned forward. “Milo has decided we live in the ice cream parlour, apparently,” she said. “Maybe it’s wishful thinking.” Milo and sugar were friends.

“It doesn’t work around you and your mother,” Sanaam said. He pocketed the compass again. “Too much iron in your blood. You must be magnetic.”

“I’m sure he’d be thrilled to fix it for you,” Maggie said with a smirk.

“You bite your tongue, Mag-Pirate. Milo dissolves in criticism. It’s like that postcard with the raccoon trying to wash cotton candy.”

It wasn’t really broken, both of them knew that, and he didn’t want Milo to “fix” it. He had no idea how the damn thing worked and he doubted Milo or Ann could enlighten him in any meaningful way, but he liked having a magic compass that “knew” when he was home. Whether Milo had calibrated it to Maggie and the General specifically or it had an emotional awareness that Sanaam himself lacked. Or if there was some kind of malfunctioning metaphysical beacon that had nothing to do with love or family at all. It wouldn’t be any fun if he knew it was something like that.

“I saw a movie where a guy falls into a vat of acid,” Maggie said. “It boils like a deep fat fryer. And then…” She dramatically lifted a clawed hand and bobbed it in front of her face. “Just the skull. Milo takes criticism like that.”

Sanaam rested his cheek on his hand. “You know, sometimes I worry about abandoning you to grow up in a slum, but then I remember the kind of person you are.”

“Dad, seriously, there’s people on Saint Matt’s who can’t afford shoes. You left me there.”

“On Saint Matt’s you don’t need shoes,” Sanaam said. “And if you really must have some, Ziyah at the market will do you some sandals out of an old tire, on credit! We take care of each other on Saint Matt’s.”

“Where the heck does he get all those tires, anyways?” Maggie said.

“I don’t know.” Sanaam flung a gesture. “There’s a bus…”

“Okay, that’s four…”

“…People have those little motor scooters, and bicycles.”

“That’s too small for shoes.”

“Maybe he orders bulk surplus from Wakoku, I don’t know. I’m not the only one making deliveries.”

“How long did you live there and you didn’t think to ask the guy where he got all the tires?”

“I was too busy wondering how come Aquila has a big red dot on it,” Sanaam said.

“It’s a storm,” Maggie replied.

“Yes, we know that now, Mag-Pirate. Do you want to nip back in time and leave a memo for the gentlemen who wrote my encyclopedia?”

She snickered. “That’s the one that doesn’t even have Dis in it.”

Sanaam bowed his head and interlaced his fingers, “Dear gods, please bless my daughter with a smug little child of her own one day who simply can’t believe all the dumb stuff her Mommy used to think was true.” He rolled his eyes and scoffed, “‘Oh, gods, Mom, nine planets? Were you sad when the dodo died the first time?’”

“Hey, you’re the one who told me there were moa on San Matteo and you used to eat ‘em,” Maggie said. She scooped a bite from her banana split and examined it. “My ice cream is soup.”

“You should have gotten something with a straw in it, Mag-Pirate,” Sanaam said. He sipped his chocolate malted, which was liquid but not yet warm. “That’s just poor planning.”

“I don’t have enough data on how long it takes us to normalize after we figure out we’re saying goodbye again,” Maggie said. She ate ice cream anyway. “Sometimes it sucks more than others.”

“It always sucks,” he said. “Do you think you’ll come next time?” He shook his head. “I don’t mean next time I come home, I don’t even know where I’m going next time I come home. It might be someplace with cannibals. I mean next time I ask you.”

Maggie frowned and considered. “I’ll try really hard,” she said.

◈◈◈

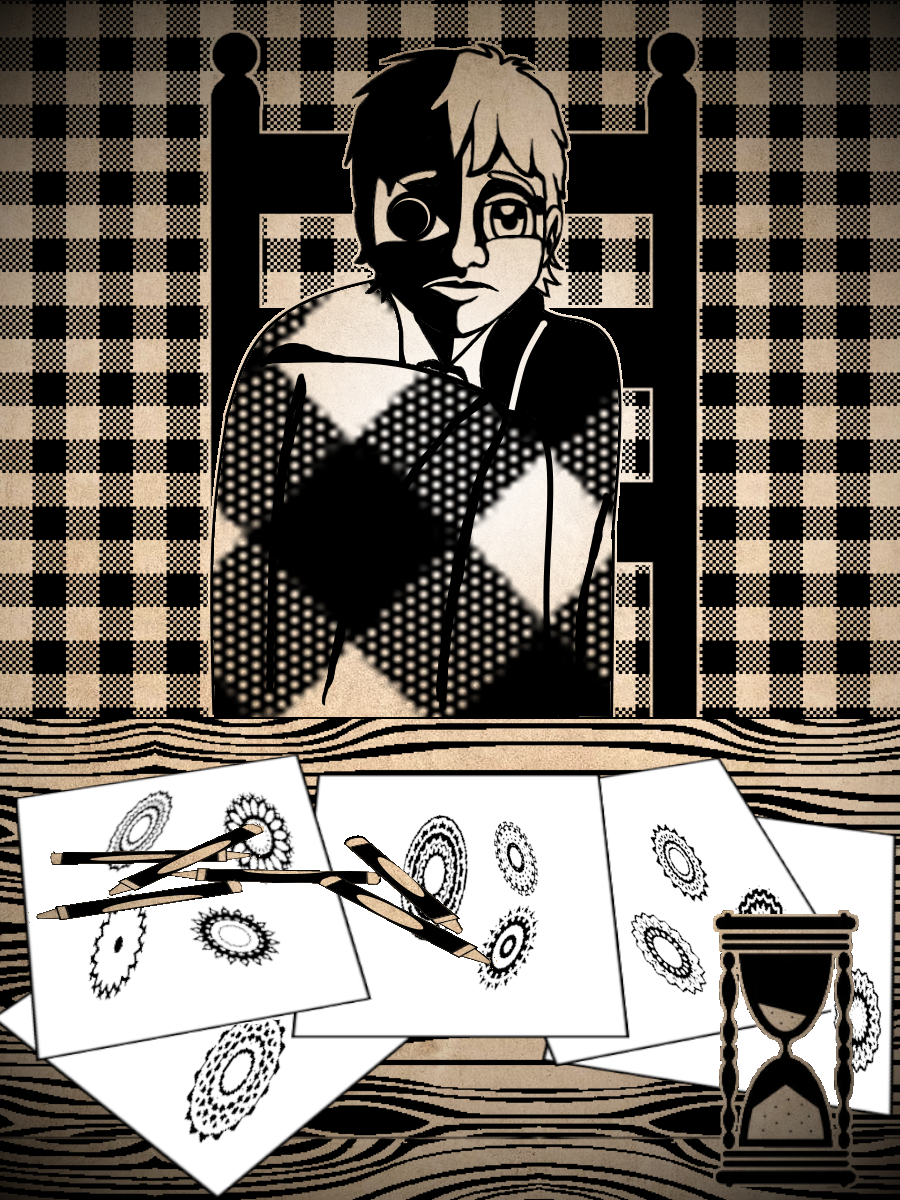

They arrived home with hand-packed ice cream of four different flavours in a large paper bag. Erik and Calliope were in the front room, taking advantage of the light for what was apparently a practical art lesson. Calliope was expounding upon a mobile that had been jury-rigged from a coat hanger and a large wooden spoon.

“It’s contrast, Erik. You get it? I don’t want to strangle your artistic vision here, but you said you wanted more stuff in it.”

“Not… unhappy,” Erik managed. That was a problem. He slowed down for good stuff and bad stuff — even in-between stuff if it was big enough. “Surprised. I didn’t… think… cans…”

There was also a fork with bent tines that made a clattering noise which Calliope and Lucy both seemed to find amusing — so he didn’t want to say to get rid of the soup cans. It was just weird. Smiling, happy clouds and stars and a crescent moon, like how he imagined in a regular nursery, and then soup cans and a fork and a red kitchen sponge cut into a circle.

Then again, she went into the kitchen to fix it, so he didn’t know what he thought she was gonna do.

“It adds dimension, you know? Hi, you guys. Did they have pistachio? Lucy’s looking at it this way.” She held the hanger over her head and peered up at it. “There’s a lot of negative space…”

“Spumoni,” Sanaam said, indicating the bag. “Your second choice and Erik’s first.”

“Cool, we’re ice cream twins.” She frowned. “That would make a good licensed character. Like on pencil boxes…” She handed Erik the mobile and wandered into her room. “I wonder if they are ice cream or they just like ice cream?”

“Is that for Lucy?” Maggie asked.

“Well, I don’t need one,” Erik said. He held it up and tried to have a look at it from Lucy’s point of view. “If I get bored I can go to the movies.” He snickered. “Calliope thinks it’s… mean to call it a… mobile when Lucy isn’t, but there’s already a… thing called… ‘stationary.’”

Maggie smiled and shook her head. Yeah. What do I need with palm trees and running water when I’ve got stuff like this at home? “I bet I can hang it up for you and get it to spin,” she said. “I can anchor it to the bassinet. Like the Sea Breeze. Is Uncle Mordecai mad you took one of his spoons?”

“We sneaked it and didn’t tell him yet, but Auntie Hyacinth says we can have all the messed up silverware we want.” She’d said “bitched up,” actually, but there was an adult in the room.

(Hyacinth didn’t count. He was still trying to decide if Calliope counted.)

“Calliope wants to make a wind chime,” he added. He sidled a little closer and asked softly, “You gonna stay… home for… Yule?” Intuitive he might have been, but he was not quite suave enough to be subtle.

Sanaam cleared his throat to conceal a laugh and turned slightly away, offering privacy.

“Yeah, I guess,” Maggie replied and shrugged. “This year. I wanna play with Lucy and Calliope some more. Daddy would, too, if he could, you know?”

Erik beamed. After a moment’s fumbling he freed one hand and signed her a thumbs up.

Calliope peeked out of her bedroom clutching a green pencil. “Hey, Maggie, can I put ice cream on your head? I wanna see if it looks cute or creepy. It’s really easy to make twins creepy.”

Maggie self-consciously tugged on one of her pigtails, “Do you mean, like, actual ice cream on my actual head over here?”

“Oh, wow, can I?” Calliope said. “That’d be great! I could work out the colour palette! Spumoni has gradients!” She vanished again. “It has to be pastels…”

Hyacinth peeked out of the kitchen, “Do I hear ice cream out here?”

“Put it in the basement, it’s too close to dinner!” Mordecai said distantly, perhaps impeded by something that required stirring.

“You’re not the boss of me!” Hyacinth shot back.

“He’s the boss of me, though,” Erik said sadly.

“You can sneak it, Erik, we have a spoon,” Maggie noted, indicating the mobile.

“But I’m sharing with Calliope and I don’t want to eat it out of your hair…”

Sanaam watched the comfortable chaos envelop his daughter. He abstained, to the extent that he was able, though Hyacinth demanded the bag of ice cream from him. He was used to disentangling himself this way. He was always saying goodbye.

Maggie’s home, he thought. Even if she’s not ready to admit it yet. He was smiling, but it felt a lot more complicated than that.

He might pick her up sometime next year, if he timed it right, but he didn’t think he’d ever get her for Yule again, real Yule. It would be years between visits to the island, that wouldn’t change — or if it did, the interim would get longer, not shorter.

She’d made her nest, and she stole herself a family to decorate it with. If she left them too long, they might get disorganized. Okay, I need you over here for the fatherly advice, and you for fun, and you give me some love and admiration… Not that she minded having a distant mother and an absent father, but she needed more. Like he had plenty of extended family and support but he still required an encyclopedia. And a boat. And several continents.

It’s just so small here… And there’s a hole in the roof.

He felt sorry for her, but he envied her too.

“Okay, okay,” he broke in. “Listen, I will put the rest of the non-Hyacinth ice cream in the basement. Mag-Pirate, if you’re going to let Calliope paint your hair with that, please take it into the yard so we can at least pretend Hyacinth cares what the house looks like inside…”