Hyacinth was quite used to knocking on her door in the small hours of the morning. She even recognized the knock. It was Ann this time, although quite a bit less fluttery and urgent than when it was about the giant Yule tree in the front room.

She sounds annoyed, thought Hyacinth. Must be a stranger. I wonder if someone broke in?

Ann and Milo were light sleepers, although Milo was slightly less likely to come out of 201 and try to help when trouble showed up. Usually Maggie and the General dealt with the occasional would-be thief, but sometimes Ann and Milo alerted first, and they felt it more appropriate to alert Hyacinth than to wake the General.

Hell, you guys, thought Hyacinth, wincing in the glow of her automatic mage light. She staggered to the door with her hands out like a cinematic somnambulist. You have the authority to deal with these things yourselves. I mean, Milo almost strangled Calliope’s brother, clearly you…

She opened the door and was greeted not by a furtive person in a white nightie, but by Ann’s smiling, painted face and a gloved hand holding a calling card with a tinted still of a pink woman on it.

“Oh, you’re in!” Ann said brightly. “I am glad! Good morning, Hyacinth! You know, I was very surprised to find out this evening at the club that Cerise had been by the house yesterday while Milo was at work… You remember Cerise, don’t you? Your intended?”

She was beaming like a searchlight. It was like getting hit in the eyes with a baseball bat.

“…and you were not in. I thought to myself, that is very odd, Hyacinth is always in. She is a doctor. In fact, Mordecai also thought you were in, but he took Cerise all over the house and they couldn’t find you! Isn’t that odd?

“You know what is also odd? The fact that Cerise has sent several lovely cards inviting you to the Black Orchid and offered to get you in for free and you haven’t been! You haven’t even written a single reply! And then when she comes to the house so you don’t have to abandon your patients, somehow you are also not here! You are a funny person, Hyacinth! Truly!”

Ann’s belligerent smile faded into a scowl. She shoved Cerise’s calling card, which the poor thing had been too embarrassed to leave at the house, into Hyacinth’s chest.

“I have been making excuses for you,” she hissed. “But you have become too obvious for me to explain. She is convinced you do not like her, but she doesn’t know why. Will it be my responsibility to make up a pretty story to spare her feelings for you, or will you at least write her some kind of break-up letter like an adult?”

“Ann, I wasn’t actually going to marry…”

Ann jabbed a finger in Hyacinth’s chest and propelled her back into the bedroom. “You know very well what I mean by ‘breaking up,’ Miss Hyacinth!” she said. “She thought you were going to be friends! She was excited about you! She wanted to take you to a nice café with outdoor seating and insult people all afternoon! And I asked you, I specifically asked you not to toy with her emotions this way, and you’re doing it anyway! What is the matter with you?”

“Brain damage,” Hyacinth said.

“Bullshit,” Ann said.

Hyacinth sighed.

◈◈◈

Nina was blue, to begin with. Dark blue like midnight with a full moon and no clouds. And she always wore a yellow bandana with red flowers on it around her throat, even to bed.

Hyacinth was not particularly bothered about blue people. Or coloured people. Or any kind of people. David had worn out her being-bothered-about-things set of gears, only a few of them still functioned, and then intermittently.

To rate even a raised eyebrow, Antonia Pasternak would need to be a famous soprano who spent her free afternoons wrestling alligators in aspic. Nude. A daughter of Prokovian exiles with a crate full of Screamin Jay Hawkins cylinders who had volunteered her god-calling ability out of disdain for her ancestral homeland was hardly worth noting. One story out of a hundred others Hyacinth had been introduced to when she got assigned to her unit.

Nina did have a practically perfect pair of tits, though. A solid ninety-five out of a hundred. Round, heavy but not floppy, a good size for serving a caffe latte for two at a wrought iron table under a striped umbrella. Friendly tits.

Hyacinth was happy to be informed that in her position as a medic she would be collaborating closely with these tits and sharing a tent with them. Her intention was to observe them from a respectful distance, maybe investigate the nature of Miss Pasternak’s foundation garments for future reference, politely put up with the music at a reasonable volume, and maintain nothing beyond a cordial working relationship otherwise.

There was a problem, though. There was a human head attached to the tits and this head contained a personality. Several of them, actually, on demand. But the original occupant was not just a meek and unassuming placeholder that could be shunted aside and ignored. Nina had a sense of humour. And a laugh. A really great laugh. And just enough sarcasm to keep it interesting, like a scream in the middle of a crackly blues cylinder.

Hyacinth theorized that when it was your job to get kicked out of your own body and watch yourself get driven around like a rental car, you developed a strong sense of identity and self-determination like an immune response. Hence Nina’s persistent refusal to be reduced to a pair of friendly tits.

Nina thought she was shy, at first. Nina thought she was rooming with a shy person! And she took that like a challenge. “Come on! We might get shot tomorrow! It’s our last night on earth and you want to waste it reading novels? Put down the book! Let’s make fudge!”

“Attractive people are fuh… are screwing each other in my novel, Miss Pasternak.”

That didn’t faze her. “Boys or girls?”

“Gay boys in bondage. I am reading Gay Boys in Bondage by William Shakespeare.”

David and Barnaby would’ve known she was blowing them off with a response like that, Nina either didn’t or decided to one-up her by pretending she didn’t, Hyacinth still wasn’t sure.

“Read it out loud, then. I’ll melt the chocolate over the lamp.”

Hyacinth marked her place with a finger and put the book down. “They let you have chocolate?”

“I’m a human Rolodex of living weapons, Miss Dickenson,” the blue woman said primly. “They let me have whatever I want. I have a person assigned to me!”

(This person was called “Mike,” he did not room with them, and it was several months before Hyacinth realized he was supposed to be in charge of Nina instead of some kind of servant. “I think they try to fix us up with people we’d like to have sex with,” Nina said of him. “So we’ll care about them. It’s not working for some reason.”)

She thudded the bag of foil-wrapped candies on the nightstand and said, “Read to me from William Shakespeare’s Gay Boys in Bondage or I shall go away and come back with someone who can explode your head. Without a gun.”

Hyacinth discarded the book. She drew her legs under her and sat forward like an eager teenager at a slumber party — one of which she had never had. (David would’ve humiliated her by showing up in a nightie and demanding to braid everyone’s hair.) “I thought you just called healers! What did they put you in my room for?”

“I’m the only one around here who can hold Auntie Enora, so they like to save me for that, but I don’t discriminate, personally. And you are in my room, Miss Dickenson. Like a complimentary basket of fruit from the management.”

“I am not complimentary,” Hyacinth said. “And I’m not a Dickenson. It’s an alias, for the forms. I’m a fraud. I forged a new birth certificate after my parents threw me out.”

Nina had grinned, perhaps already deducing in her frustrating head that if Hyacinth’s parents had thrown her out, they must have had some reason. “Have you been ignoring me because I didn’t have your name right?” she said eagerly. “Like a cat? What do you want me to call you?”

“Just Hyacinth is fine.” She offered her hand. “I think I’m a corporal or something. They upgraded me when I got my certification so I can boss people around. What’s this little gold teepee thing mean?” She turned and displayed the badge on the sleeve of her blazer.

“‘Caution: Rich Tent-Dwelling Savage,’” Nina said. She shook the hand. “I’m Nina at the moment, Hyacinth the Cat.” She smiled. “I’m the one with the flower bandana,” and her fingers twined around the decorative knot at the base of her throat. “I never let any of them wear it.”

Nina leaned back and folded her arms with a huff, “Now, if you don’t provide me with an amusing tale of gay boys in bondage, my threat still stands. They can always send me another fruit basket. The last one got shot. …Or perhaps that’s just what I told them.” She drifted away mysteriously and began to unwrap chocolates.

Hyacinth was good at invention on a moment’s notice, and she did prefer not to have any more head injuries. Holding her copy of The Guns of Navarone insolently upside-down, she produced a plausible story with a lot of cruel whippings in it and turned a page exactly once.

But they could’ve just been friends. She’d had friends before! Barnaby was a…

(Even now, she couldn’t bring herself to think that.)

Anyway, she was theoretically capable of just being friends with a woman! Even if that woman had ninety-five-percent perfect tits and a charming personality! If Nina had nailed up some boundaries and stuck to them, Hyacinth would have respected that.

Except Nina and her personality didn’t want to nail boundaries.

“Is this because you’ve got other people walking your body around all the time?” Hyacinth had demanded, twisting away. “Do you just not care anymore?”

“It’s because I’ve got other people walking my body around all the time that I had to decide very fast who I am and what I like and stick to it,” Nina replied reasonably.

“Is this like that goddamn flower bandana?”

“The goddamn flower bandana is for the outside,” Nina said. “For your convenience, kotik.”

(Kotik. Gods, it had been an age since she thought of kotik. They’d been working together for nearly a year before she even got upgraded from “Hyacinth the Cat” to “kotik.” And Hyacinth was certain it was because she kept putting Nina off, not the other way around. By then, Nina caught her swearing in Prokovian, and knew she understood enough to know that was still “cat.” “Your accent is almost as bad as mine!” she had exclaimed in shock.)

“…knowing I like girls is like knowing I like Screamin Jay Hawkins. For me. Inside.”

“And you’re very sure you haven’t put a spell on me?” Hyacinth said acidly.

“It’s cute when you’re insulting, kotik,” Nina said. “I don’t need a spell.” She widened her eyes, threw back her head and emitted a diabolical laugh. “Because you’re mine!”

Hyacinth was all right having a fling with a pretty lesbian when every night might be their last night on earth. Well, after she had adjusted from confining her relationships to boys with fast cars — whom she did not like. The boys, not the cars. The cars were fun.

Nina was also fun. And, Hyacinth had been able to tell herself, no more attached to her than the cars. Or a basket of fruit. Presumably they would consume each other until they got down to the boring waxed apples and threw the relationship in the trash, or they would get transferred or die. However they wound up, there wasn’t a future involved.

Until Nina decided there was.

They’d been lying on a blanket on the floor. The cots weren’t big enough for two. Both of them without tops, with a single oscillating fan blowing the humid air over them. It sounded like a kid with a foil pinwheel, and had just as much effect on the heat. Nina’s bandana was soaked with sweat.

She had laid a delicate hand on Hyacinth’s belly, smiled and said, “Do you think we’ll see each other after the war, kotik?”

“There isn’t any ‘after the war,’ Nina.”

“Certainly there is,” Nina said. “I can have it whenever I want it. I’m just annoyed at those dirty Sergeis. I don’t know why in every god’s name you enlisted.”

Hyacinth shifted uncomfortably and turned away. “I don’t have anyone to go home to until it’s over.”

Nina sat up. “This person you are pining after is old and unattractive. And a man. And you hate him. You’re not talking about your family, are you?”

“Oh, gods, no, I hate them more.”

Nina stood up and lit a cigarette on the lamp. She said she liked them because of Auntie Enora. Hyacinth thought she liked having a tiny wand of smoke and fire in her hand to give her gestures a little more emphasis. (And it made her voice more gravelly for singing. No matter how many times they knocked her down, she always came back singing.)

“Regardless of why, you’re in it for the long haul now,” she said. She took a drag and blew a smoke ring. “I believe I’ll follow you, kotik. Would you like that? If they transfer you, I’ll come along. They can’t stop me. I’ll be a resistance fighter like those gentlemen in Navarone, but I’ll do my very best not to betray you at the last instant. What do you think?”

Hyacinth recoiled. “Why would you do something like that?”

“Oh, I don’t know. Money, I suppose,” Nina said. “Kompromat. I manufacture kompromat on a daily basis, but let’s assume I started caring for some reason…”

“No! Why would you follow me around, you stupid idiot? What for?”

“Companionship, perhaps?” Nina said. She examined the trail of smoke she had drawn. “It’s not as if either of us wants a priest or a barrister. So I’ll just say I’ll follow you. I’d like to meet this person at home whom you hate.”

“No you wouldn’t!”

“Of course I would. I love you, and associated things.”

As short sentences went, “I love you” was not nearly as upsetting as “I’ll follow you.” Hyacinth was willing to admit loving Nina, they’d both said it ages ago. Hyacinth also loved chocolate chip cookies — but she wouldn’t like them to follow her around for the rest of her life and meet Barnaby! Chocolate chip cookies came in batches of a dozen and then they were over. If Nina wanted to follow her around, not only after their last night on earth but after the entire war, where would it end?

Would it end?

I don’t want to love you forever! I can’t!

The words wouldn’t come out of her mouth, but maybe her expression was enough. Nina stubbed out her cigarette and smiled. “I was only teasing you, kotik.”

“No you weren’t,” Hyacinth said dully.

“No, but we can pretend I was until you’re ready to make a decision.” Nina stood and extended her arm. “Come back to bed.”

“Fuck off,” Hyacinth said.

She walked to her C.O.’s office and demanded a transfer. She did not bother to put on a shirt. Her C.O. naturally assumed she had just been assaulted and someone had taken her shirt, and they ought to involve the police and perhaps a court-martial in this transfer request.

She had to explain to several officers that she was a brain-damaged person who did not always remember her clothes — and, yes, the part about the brain damage was in her file — and by that point Nina had arrived with her shirt. Which she did not want. Either of them.

She was eventually convinced to accept the shirt, and Nina departed with some of the officers to make up some plausible story that did not involve having sex with her roommate.

“All right, Sergeant Dickenson,” said her rather flustered C. O. “Why do you want a transfer?”

“Intolerable cruelty!” Hyacinth declared.

“…That is a reason for a divorce. Just a moment, I have a form.”

Hyacinth ticked the box that said “other” and wrote in, “irreconcilable differences.” In retrospect, she thought that was also a reason for divorce. But they shouldn’t put a blank box on the form if you weren’t allowed to write in whatever the hell you wanted.

Her C.O. accepted the form and said there would be a response in six to eight weeks. And Hyacinth said, “What?”

She had to go back to her tent with Nina. At the time, she had regretted not saying Nina assaulted her. Then they wouldn’t have made her go back and sleep in the same room. It felt like an assault, anyway.

Now, she was glad. Nina didn’t deserve that.

Nina probably also didn’t deserve to be screamed at, she just wanted to understand. But Hyacinth thought Nina had already taken quite enough from her — things she didn’t even know she was giving, like trust and commitment — and she wasn’t about to give any more. Not even understanding.

“No! You’re going to go over there and go to sleep and I’m going to go over here and read The Guns of Navarone for the hundredth time and that’s final!”

She lay there on her cot with her light on and her book open, not reading, listening to Nina replay “Monkberry Moon Delight,” only that, again and again and again.

Nina favoured “Monkberry Moon Delight” in times of emotional and physical distress, not unlike David and his damn album, but she liked to sing it. There was no singing, only an occasional stifled sob which Hyacinth told herself she didn’t hear. At the time, it had only seemed to underline the fact that this relationship was doomed from the start.

A good while after the music had stopped, and with bluish dawn leaking in the edges of the tent, Hyacinth got up and packed a canvas duffle bag with a few of her novels, some civilian money and little else. Military-issue items would mark her as a deserter. The uniform couldn’t be helped, she would ditch it as soon as she could buy or steal some normal clothes and blend in.

You could get away with a lot if you kept your head up and looked like you knew what you were doing. She melted her way through the barbed-wire fencing and headed for the nearest town.

When she was half a mile down the muddy dirt road, it started to rain, and she found out they weren’t kidding about the hypothermia risk from cold, wet clothing even in warm weather.

She didn’t go back for her greatcoat. Sometime after dawn, she found a cheap corduroy coat with a shearling collar hanging on a nail outside a farmhouse, and stole it. It helped a little. She made it to town without dying, anyway.

There, she dumped her sodden novels in the trash, put the coat in the duffle bag, and spent her money. It was enough for some clothes and a train ticket. When she needed more she could offer to make repairs — on objects or people, whichever was handy.

She went home.

Not to her family in South Hestia, away from the fighting. She hadn’t seen those people since her father died, and she had gleefully torched any remaining bridges with them at that time. She went home, to David’s townhouse in San Rosille.

(Technically it was Barnaby and Hyacinth’s townhouse in San Rosille, but they hadn’t done much to it since David died and his things were still all over the place. They only ate breakfast and slept there, occasionally nodding hello in passing.)

It occurred to her later that she could’ve gone to Marabou, David’s house in South Hestia, which to the best of her knowledge they also still owned. She owned it, but that was just on paper. Barnaby wasn’t any more likely to be there than in San Rosille, he was a state augur and he had to work. It would have been smarter, for her personal safety, and her history would’ve been very different indeed if she’d done that.

But she didn’t think of it at the time, not even with plenty of quiet, novel-less hours spent gazing out the windows of trains. She wanted to go home.

She arrived just after sunset, in faint purple twilight. The streetlamps hadn’t been lit yet, but there were lights on in the house, and she could hear the radio playing. She had smiled.

He was not going to be there. She had told herself and told herself… Even at the time! On the way there! Obviously, he was not going to be there. Renters. If there was anyone in the house it would be renters and that would suck because she’d have to find some other place to stay. That was obviously renters in her house which Barnaby had no right to rent by himself and she should’ve been pissed off already.

But she had smiled. And when she peeked in the wavy glass of the windowpane and saw a sweet little family gathered around the fireplace in the parlour with the mother doing embroidery in a hoop and the little boy in a sailor suit running a toy car back and forth on the rug, it was like getting kicked in the chest.

She banged on the door. “Where the hell is Barnaby Graham?”

“Excuse me?” said the set-piece of a father the fates had provided for her. He had a fussy little manicured moustache, a cable-knit sweater vest, and a pipe, of all things.

I suppose if I punch this person and get arrested I’ll have a place to sleep tonight, Hyacinth thought. But she prefaced it with, “Barnaby Graham! Your landlord who only has sole ownership of this place on paper because we never bothered to straighten that out! Do you have an address you send cheques to? I’m going to find him and sue him!”

“My dear woman, we own this house,” the faceless walking cloud of familial clichés said. “Please leave.” He gently closed the door between them.

He had no right to sell it! Legally, oh, yeah, sure. But he had no moral right to sell it! She should’ve been furious. She should’ve made a scene. She should’ve spent that night in a jail cell. She was mad about it even now.

But when that man with the moustache closed her own door in her face, she had only turned and walked away. To the end of the row of houses. There were three stuck together and David had the middle one. Used to have.

She turned into the alley, sat down on her duffle bag, and cried. She had already been crying. She supposed she had started crying when she saw that cute little family in her crazy house that had never required a cute little family before, there just hadn’t been tears until she sat down in the alley. And then she bawled like a baby.

It wasn’t about the house. The house didn’t want crying over. She had never been particularly happy in that house, and she had no affection for David’s things… or Barnaby, another of David’s things. Or even her own things.

It was what she expected to find in the house. He was supposed to be there, damn it! She knew he wasn’t, but he was, because her world was in pieces and she wanted to have him make her a gin and tonic and tell her she had done the right thing in tearing it apart. You couldn’t be expected to stay, Alice. You hate people. We both do. Now dry your eyes, and why don’t we go to a show?

She didn’t want Barnaby or the house, she wanted Barnaby in the house. She wanted to go home!

Home wasn’t a place, it was knowing where she belonged. Nina had taken that away from her. That was a problem that needed solving and every step she had taken since then had been towards solving that problem, and now she had arrived at the solution, she was there, and there was nothing for her at all. She had walked across a country on blistered feet to find out she didn’t belong anywhere.

Except maybe with Nina, but she had closed that way behind her. She was a deserter. She couldn’t go back.

Even if she didn’t get thrown in the stockade, what would she say?

Hi. I’m sorry I screamed at you and deserted the army to get away from you. Let me explain. Do you get how a bag of chocolate chip cookies wouldn’t be anywhere near as fun to eat if there were always more of them? No, huh? Oh, and here’s the police. We’ll have to pick this up later.

She couldn’t go back.

Eventually, she defined her new problem (“I need a place to sleep tonight,” so much easier than “I’ll never have a family like the one that’s living a hundred feet away from me in my house”) and started moving towards a new solution. She was like a shark, she had to keep moving to breathe. Any further problems that sprang up in her path could be devoured like fish to sustain her.

She hadn’t run out of them yet.

But sometimes… sometimes there were remoras that she needed to scrape off. Like Nina. Better to quicken her pace so that they never got attached in the first place. Less pain for everyone involved.

Only this angry person standing in front of her door at three o’clock in the morning didn’t understand that, and she didn’t know how to explain.

◈◈◈

“Ann… Do you get how a bag of chocolate chip cookies wouldn’t be as fun to eat if there were always more of them?”

“I’m not buying it’s the brain damage, Hyacinth, so just stop.”

Hyacinth sighed. “I don’t know how to say it.” She turned her head away. “You’re right about me, and it’s just as well you and Cerise find it out now. I run off on people. I don’t do friends. I do brief stops like a commuter train and I never turn around and go back. Even if I run somebody over. That’s the kind of person I am.

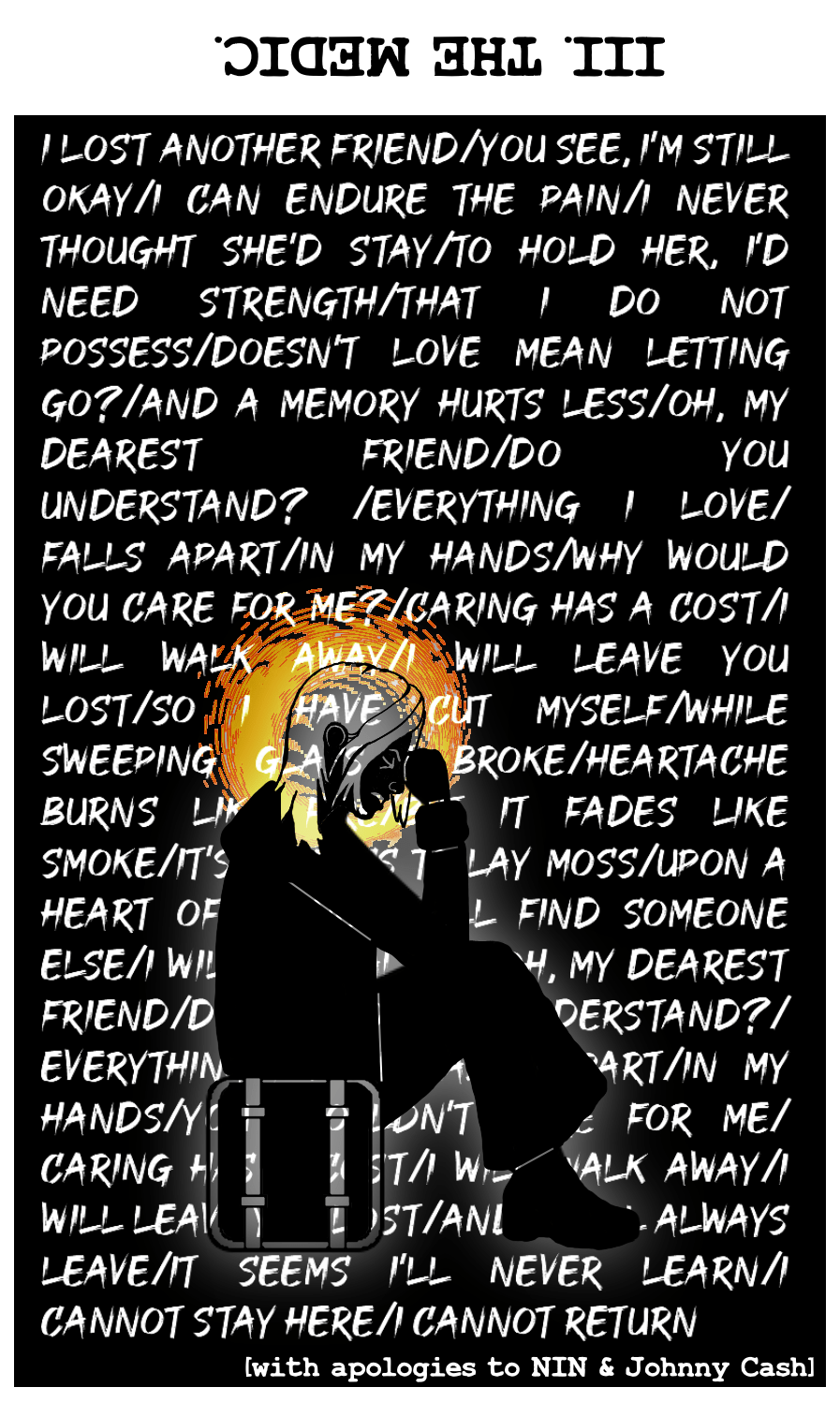

“You probably should break up with her for me. I don’t know how to do that. I left the only woman who ever loved me without even saying goodbye. The last thing I said to her was I was gonna go read The Guns of Navarone, and I yelled it at her because I was mad she wanted to stay with me forever.

“I don’t want to do that to Cerise. The only way I know how to keep that from happening is to leave before she likes me too much.”

“She didn’t actually want to marry you, either, Cin,” Ann said.

“I don’t like anyone to keep me, Ann. It doesn’t matter if it’s to have a family or just to insult people walking by an outdoor café.”

Ann lifted a hand. “Hyacinth…”

…Aren’t we your family?

Don’t, Ann. Maybe we’re not. And she doesn’t like me.

Or maybe she doesn’t want to say we are, Milo.

She put her hand down. “I’ll talk to Cerise, but I am not happy about this. You didn’t have to do this.”

“I’m sorry, Ann. But don’t tell her that. It’ll be better for her.”

“Perhaps.” Ann turned halfway and paused. “Where did you hide from her, anyway?”

“I saw her through the front window and ducked into Room 101.”

“It let you?”

“Apparently.” Hyacinth made a weak smile. “I can be quite a charming psychopath.”

“No, you’re not that,” Ann said. She went back to her room.

Are we… not mad at Cin anymore?

I’m not, Milo. I’m frustrated and disappointed.

Like when you want me to be brave about something and I’m not?

Yes. But I can’t push her like I push you.

…That must be nice for her.

Ann applied cold cream to her makeup and got ready for bed.

◈◈◈

Hyacinth heard the stairs come down, but she didn’t go to the door.

“Are you decent, Alice?” the voice said.

“No, Barnaby. Never.”

He opened the door and looked in. “It’s nothing I haven’t seen before.”

Hyacinth pressed both hands over her eyes. She did not sit up. He could’ve been some kind of auditory hallucination for all it mattered. He wasn’t going to tell her anything she didn’t already know, like a carnival fortune-teller. “Do we still hate everyone, Barnaby?”

He sat on the bed, which quite spoiled the effect. “I do. But I must admit I was never quite sure about you.”

“About hating me or about me hating everyone?”

“Yes.”

“Will you make me a gin and tonic?”

“You always made your own gin and tonics, Alice. I don’t know where you got the idea I would’ve been nicer to you because you showed up at the door wearing a stolen coat and crying.”

“You used to make them when David was dying.”

“That was that bird of his. He knew how to open the icebox. Ravens are clever.”

“I wish I’d been nicer to him,” Hyacinth said. She sat forward and rested her chin in her hand.

Barnaby had found something interesting to examine in the configuration of socks on Hyacinth’s dresser. He looked older in profile. Maybe she was used to having him coming right at her with his mouth open, yelling about some incomprehensible thing. It was distracting. This was almost like he was some kind of person, a tired one that had been badly used.

“He didn’t deserve it,” he said.

They didn’t hug. They didn’t do things like that. Mainly they expressed their affection by consuming liquor near each other. She put her hand on his hand and they stayed like that until he got annoyed with the socks and left the bed to rearrange them.

“She would’ve liked you,” Hyacinth said.

Barnaby turned and smiled. “Ah, but I would’ve hated her.”

Hyacinth thought, Then it’s just as well.

Barnaby thought, And it’s too bad.

She told him she paired up her socks because she wanted them that way and shooed him back to his room. After considering her narrow, empty bed with distaste, she got dressed and went downstairs to wait for Calliope to get up with Lucy. Lucy would need a bottle. Maybe something else would go wrong. You never knew!