Hyacinth advanced upon her, pointing a finger, “Now, don’t you start with that!”

“Put that thing away,” said the General. “You are not addressing a man or a child.” She nodded at Milo. “Or whatever he is.”

“Milo, here,” said Maggie, softly. She handed him a glass of water and led him to a chair. He gratefully sat and disengaged from the proceedings. Maggie sat next to him and watched with queasy interest. When her mom got into an argument, she took no prisoners.

The General was a hard woman, and civilian life had done little to soften her. She was round where Hyacinth was flat, but it was not a comfortable roundness. She did not invite hugging. She seemed to have developed hips and a chest for intimidation alone, like epaulettes and shoulder pads. She wore her brown hair quite severely short and did not bother to style or even comb it, keeping it neat by sheer force of will. She saved her full uniform for pension days and mostly wore dark green and dark blue dresses in stiff fabrics that squared off her edges.

She did still wear her greatcoat and was wearing it now. It had been somewhat altered in the service of medicine. The brass detailing was gone, the ribbons and medals that had once been pinned to the breast were now sewn on with thread, and the medals lacked metal, being reduced to mere ribbons or nothing at all. There were still more than enough to be impressive. Her replacement buttons were impeccably matched to the greenish blue shade of the fabric and perfectly sized.

“Ill-advised attempts at intimidation aside,” the General continued, “you can’t deny that he did what they want him for.” She smoothed the flyer flat on the kitchen table and pointed with a rounded nail.

…in connection with a possible terrorist attack in Canburry Square…

“He’s not a terrorist!” Hyacinth said.

“Isn’t he?”

“He held the walls during the siege! He was on your side!”

“But not always.”

And that was why Hyacinth had prefaced this argument with don’t you start with that!

“He was a kid!” she cried.

“No, you were a kid. And you managed not to foment a revolution at the tender age of thirteen. Nor I, at the age of five.”

“It’s not as if they managed it,” said Hyacinth.

“I do not believe that was my point.” The General enumerated the following on her fingers, “He conspired to overthrow the government, he performed a malicious deconstruction in Canburry Square — and might I add, he incited a citywide riot?”

“You know very well why he did that. You saw what those two did to Erik.”

“And if that is sufficient excuse, then I imagine it will come out in the trial.”

“The trial!” said Hyacinth. “Do you imagine a coloured man can get anything approaching a fair trial in this city — in this country — on this continent?”

“I imagine the legal system functions, yes,” said the General. “As one does.”

“You’re delusional,” said Hyacinth.

“And what is it exactly that you intend to do, if not subject him to the woes of a trial? Break him out and do what with him?”

“Bail him out,” said Hyacinth. “And bring him home so I don’t have to tell Erik his uncle’s in jail.” She threw up her hands and acknowledged the dead end. “Then I don’t know what.”

“It’s not as if they are in any condition to run,” said the General. “Not the both of them together.”

“I know that!” And Hyacinth was not about to split them up, as if Mordecai would agree to that even if she suggested it. “Couldn’t you fix it?” she said. “You can alter things, can’t you?”

“Altering government documents is treason,” said the General.

“Well!” said Hyacinth. She flung a gesture. If they couldn’t do a little light treason for a good friend, then what were they?

“Altering human minds is against the Florentine Conventions. And is a mortal sin in several religions.”

“You know, I’m not hearing you say you can’t do it.”

“You are delusional.”

“What I am is stupid,” said Hyacinth. “I don’t need your permission. I would appreciate your help, but I’m going to go down there and bail him out, no matter what you say. And what I do after that will just have to depend.”

“What help of mine do you need?” said the General.

“Well, if things start to go a bit pear-shaped, you can turn into a giant goddamned bird. Or is that against the Florentine Conventions?”

“Not that I am aware of,” she replied.

Brief silence.

“Well, are you coming or aren’t you?”

“I am coming…”

“Hosanna!” said Hyacinth, extending her arms.

“…because I believe you need to be kept on a short leash. And if it should be required that I turn into a giant goddamned bird, I will consider it.”

Hyacinth was already talking to Milo, “Can you watch Erik? Do you need to change?”

Milo nearly fell out of his chair. He held up five fingers and ran out of the room.

“I believe Milo would like either five minutes or five seconds,” Hyacinth said.

Well within five minutes, Ann appeared in the guise of a lacy orange parfait. “You are a horrible woman,” she told the General.

“You are not even a woman,” the General replied.

Ann opened her mouth and Hyacinth put a hand over it. “No, Ann. We don’t need a second round. Not right now. Please. For Erik.”

“Only for Erik,” Ann said, glaring.

◈◈◈

There was no bail.

Once they had navigated public transportation, located the nearest police station and dealt with the problem of names — Hyacinth wasn’t aware that Mordecai even had a last name, the General was able to supply it, and it turned out that he had given no name at all, they just had to say “red” — there was no bail. Also, this was perfectly legal and there was no recourse.

“Check back in twenty-four hours,” the beleaguered man at the front desk informed them. “Although, if he still won’t give them a name, I can promise you they’re not going to let him out, no matter what the judge says.”

“He has a sick child at home!” Hyacinth cried. She put both her hands on the desk to prevent herself from leaping over it to throttle the man. “What am I supposed to tell him?”

“Ma’am, that is really none of my business. Nor is the matter of bail. It’s no good trying to convince me.”

“Can we speak to someone we can convince?” Hyacinth said.

“No.”

“Can we talk to him? We’ll get him to tell you his name!”

“No.”

“Why not?”

The man riffled his papers. “They’re questioning him.”

“What about when they’re done questioning him?”

“Then he’s going into an anti-magic cell to wait for a judge.”

“And the judge won’t let him out unless he gives him his name.”

“Right.”

Hyacinth pushed back from the desk and turned away. “This is idiotic!” she declared.

“It seems reasonable enough to me,” the General said. “I don’t know why he’s suddenly decided the police don’t need to know who he is.”

Hyacinth wheeled on her, “Well, why do they?” she said.

“They’re the police,” the General said. She leaned over the desk. “Will you please let us know when the time for the hearing is set?”

“It’ll be a few hours. Do you want to leave your address?”

The General regarded Hyacinth. “No, thank you, I believe we will wait. I believe we will wait outside, in fact.” The blonde harridan was gearing up to scream. The General wrapped a fist around her upper arm and escorted her to a bench in front of the station. There were some lovely flower boxes, which were still in bloom. The leaves and the trees were bright with reds and yellows. It was actually sort of a nice day.

Hyacinth threw her off and scooted to the extreme opposite side. “Did you know about this?” she said.

“Whatever do you mean?”

“Did you know there wouldn’t be any bail?”

“No. I must say I have never needed to access the judicial system in quite this capacity before. I tend to keep better company.”

“You keep no company at all,” said Hyacinth.

The General nodded sagely.

Hyacinth bowed her head and clasped her hands between her knees. “What are we going to tell Erik?”

“Perhaps he won’t notice.”

“You are unpleasant,” Hyacinth accused.

“I never pretended otherwise.”

“He will notice,” Hyacinth said. “He’s noticing more things, and he remembers.”

The General frowned and considered with her hand to her cheek. “We could tell him he is at the store.”

“The whole time?”

“He won’t be awake the whole time.”

Hyacinth sighed. “I wonder what Ann’s told him.”

“Something ridiculous, I should imagine.”

They sat quietly for a time. The bench was slatted metal and utilitarian. The sun beat down on the thick material of their dresses. A clear, cold morning had given way to a summery afternoon.

The General undid the top two buttons of her coat as a concession, but refused to yield otherwise.

Neither one of them was wearing a hat. Hyacinth found hats uncomfortable. The General found hats unnecessary (except on pension days).

The police station was busy, with officers and civilians going out and going in. There was a little bell above the door that announced each arrival and departure. Horses went by. Bicycles went by. An occasional car went by. The bus route was on an adjacent street.

Hyacinth was stroking one arm of the bench and wondering if she could get away with stealing any part of it. Not now, obviously not now, but in the future if it should become necessary. She was also beginning to consider having that damn bell.

The General laid both hands across her thighs and boosted herself up. “I’m going to have a coffee and a magazine. Do you want anything?”

“My gods, you really do think this is going to be okay, don’t you?” Hyacinth said. “You think we’ll tell Erik he’s at the store and tomorrow they’ll set him a bail and he’ll come home.”

“Well, he wasn’t a very good terrorist,” the General said. “Or a very good rebel. Now, if we had a war in progress, I’d have him taken out and shot, but we can afford to be lenient these days.”

“You’re not in charge of this!”

“A pity, isn’t it?”

Hyacinth rested her elbows in her lap and her head in her hands. “Yeah.”

“We will be able to speak to him at the hearing, Hyacinth.”

“I suppose that will have to be enough.”

The bell went again. Hyacinth looked up, frowning murderously. She was going to fuse that thing solid…

Her mouth dropped open and she snatched at the General’s leg.

Two young men with gold repairwork in their faces were going into the station in the company of a police officer. The darker one, the one with slightly more damage, (the one she had patched with pieces of that ugly brooch) saw her and his eyes widened. Then the door closed.

“That’s them!” said Hyacinth.

“Them?”

“That’s those guys Mordecai hit with Julia!”

“I believe you should say ‘allegedly,’ under the circumstances.”

“That’s allegedly those guys Mordecai hit with Julia!”

The General folded her hands in her lap, frowning.

“We’re screwed,” said Hyacinth. She lifted both hands in surrender and began shaking her head. “Okay, we’re screwed. That’s it, we’re screwed.”

“Please be calm.”

“To what purpose should I be calm, sir?”

“If you get yourself arrested, we now know that you will have to wait at least twenty-four hours to get out.”

Hyacinth dropped back onto the bench and clutched her hands in her hair. “Okay, this is bad.”

“I don’t see how it is any worse than before. These men were not unknown to the police. They are simply here now.”

“It’s worse because I forgot about them!”

“Ah. I see how that would change your understanding of the situation, yes.”

“They’re going to say he did it.”

“Well, he did do it.”

“That will get them a trial. A real trial. And they’re going to find a whole bunch more people who’ll say he did it…”

“Well, he did do it.”

“…and he’ll have to be in jail the whole time and of course they’ll convict him, they’ll convict him of anything they’d like to charge him with. Malicious mischief. Inciting a riot. Destruction of property…”

“Domestic terrorism.”

“We have to get him out of there,” Hyacinth said. “We can’t wait for bail. There probably won’t even be any bail. Oh, gods! I wish I’d paid more attention when David got into making bombs!”

The General clapped a hand over her mouth and pushed her back against the bench. “Hyacinth,” she said, in moderate tones, “I believe you are saying — very loudly, I might add — that you would like to blow up the police station?”

“A very small part of it where there aren’t any people,” Hyacinth replied, much softer and somewhat chagrined. “Just as a distraction.”

“There is a saying about two wrongs and a right that I would like to reacquaint you with.”

Hyacinth pulled back from her and retreated to the far side of the bench. “Three rights make a left,” she muttered. She took the tie out of her fraying ponytail and put it back in more securely.

“Let’s just not be hasty. If you are bound and determined to go outside the law on this matter, a few days’ consideration and an application of strategy would greatly increase your chances of success.”

Hyacinth sat forward, “Are you saying you’ll help…”

The bell went again.

“…two-hundred pounds, and much taller,” the darker boy was saying, while gesturing. “I mean, you must realize, we were in the hospital when they did that sketch, and Edward could hardly talk.”

Pressed for confirmation, Edward replied in a dull voice, “It’s not him.”

“If you’d like to redo the sketch, I’m sure I’d do a much better job of it now.”

“Not much point,” the policewoman said. “The chances were never very good. Even this was a long shot. I am sorry, sir.”

“Oh, no, I completely understand. There are a lot of red magicians in the city, aren’t there?”

“A good few. I suppose we could do with less.”

“Ha, ha,” said the dark boy.

“It’s not him,” Edward muttered, looking away. He was already halfway down the street, it was just that his feet hadn’t managed to get him there yet.

“Have a good afternoon, gentlemen,” the policewoman said, and the bell went again.

“Ed…” said the dark boy, reaching a hand.

Edward pushed him off. “Just don’t. I did what you wanted, just don’t.” He addressed Hyacinth with cold eyes and a snarl, “You tell that man if I ever see him again I’ll kill him. I don’t need the police for that.” He walked away.

“Ed…” said the dark boy. He sighed and turned to follow.

“Wait!” said Hyacinth, rising. And… she had completely forgotten the name. It was just gone. “Sea Turtle!” she called.

The darker boy turned and looked down.

“You said it wasn’t him?”

“Yeah.”

“Why?”

“Don’t know.”

Yeah, you know, thought Hyacinth. Whether it was because he felt grateful to her or he actually felt bad about what he’d done, she’d never get it out of him, and it didn’t really matter.

“I-I may regret this later,” she said, “but right now, I’m just so damned relieved, I’d like to shake your hand.” She took one of his in both of hers. He allowed it, while still looking down and away. She was used to that sort of thing, guilty people were a little like Milo.

“How is…” He looked up and then away again. “I’m sorry, you never said the name.”

“The boy? His name is Erik.”

“He’s alive?”

Hyacinth nodded. “He has his difficulties, but he’s coming along.”

“That’s his father?”

“Not really, but close enough.”

He opened his mouth and he didn’t know what was going to come out. ‘I’m sorry,’ did not seem adequate for the situation. He was sorry, but he was also a lot of other things, confused being foremost, ashamed being paramount. “I wish them well.” He turned and made another attempt to extricate himself.

“Wait a minute, Sea Turtle,” Hyacinth said. “What do I call you if I see you again?”

“Sea Turtle is all right,” he admitted. “But if you ever need anything, my name is John Green-Tara. I live on Herald Street.”

“John Green-Tara?”

“Immigrant parents,” he replied automatically.

“Oh, I see.” Hyacinth recollected the woman in the green dress might’ve been a little dark too, but it could’ve been the torchlight. What could you tell from dark, anyway? People moved all over. Then you look at someone like Sanaam, he sure looked different, but he never stayed in one place long enough to be from anywhere. His wife and his child and his politics were Marselline.

While Hyacinth was musing on race relations, the General stepped up with a request, “John Green-Tara, I do not know if this will ease your conscience, or even indeed if it deserves to be eased, but we could use some paint.”

He nodded.

“Or metal,” Hyacinth added. “Metal is always good.”

“People are always bringing you metal, Hyacinth.” She turned back to the boy, “Bring us paint.”

He nodded, and if he had any military in his background, he might’ve saluted. In any case, he departed as one on a mission.

“I like what we have now,” Hyacinth told the General.

“What we have now is an obscenity,” the General replied.

They had gotten hold of a little paint. It was white paint, and what they had wouldn’t have covered the scrawl that the rioters had left, so Hyacinth had simply made an addition. The wall now read MAGICIANS in red, with an arrow pointing to the house, and ASSHOLES in white, with an arrow pointing to the street.

They went into the police station together (engaging that damn bell again) and attempted to negotiate Mordecai’s release. He did not make it easy on them. He still wouldn’t talk. He didn’t seem to believe that they wanted to let him go.

Hyacinth finally commandeered a memo slip from the front desk and wrote his name on it. M-O-R-D-E-C-A-I… “What was it, sir?”

“Eidel,” she replied. “No, Hyacinth, not that way.”

MORDECAI ID (scribbled out) EIDEL called, the slip eventually read, regarding YOUR SICK CHILD WOULD LIKE YOU TO COME HOME NOW! Hyacinth also checked the box that said URGENT.

She tore it off the pad and gave it to the man at the desk. “Look, will you give that to him and tell him to nod if that is his name? I want him out of here as much as you do.”

That got him out of there. He was not in what you would call real good shape when he was returned to them, but it got him out of there. Even the General could see how he might’ve been reluctant to believe that they were going to let him go.

They had mostly stayed away from his face, but a couple of good shots were enough to have laid open his cheek and run a large amount of red down the front of his shirt from his nose and mouth. They had done him enough damage otherwise that he was limping, and he would not unwrap his arms from around his middle so they could help him walk.

Honestly, the General thought, why would you hit someone in the face and then bring in people to identify them? That was a failure of basic logic. The police force in this city could do with a little military discipline.

“Mordecai, what the hell happened?” said Hyacinth, which may have been a little more humane.

“I fell down some stairs,” he muttered. He wiped his mouth on his sleeve, which improved neither.

“What stairs?” said Hyacinth.

He picked up his head and glared at her, “I fell down some stairs at the house.”

“Oh, right,” Hyacinth allowed.

They were not going to let him on a bus looking like that, not at one in the afternoon on a weekday. (At midnight on a Sigurd’s Day, he might’ve blended in.) They fed coins into a pay toilet and Hyacinth crammed herself in there with him while the General stood outside holding two purses and looking awkward. They flushed two helpings of reddened wet tissue and emerged looking somewhat improved.

“I don’t know how in the hell Milo used to change clothes in those things,” Hyacinth commented, aside.

The shirt was still a total loss, and the General, in her greatcoat, was the only one with clothing to spare. It would’ve fit two of him sideways and been adequate for three-quarters of him lengthwise.

“Can we tie it?” said Hyacinth, adjusting him. “Let’s tie it. Oh.” It didn’t look any better tied, but it did look better than a bloody white shirt.

“Just a moment,” the General said. She put her hand on the sleeve (also on Mordecai’s arm, which made him blink and look up). Amid subtle curls of white smoke, the sleeves and the hem lengthened and the slack in the body disappeared. It smelled like an iron with the setting a little too high for the fabric. “Out of respect for the uniform,” she explained.

“I knew you could alter things!” Hyacinth cried.

“I never said I couldn’t,” the General replied.

Mordecai peered narrowly at the ribbons on the breast. “You’ve got an Imperial Medal of Honour?” he asked. He might be forgiven a little absurdity after the morning he’d had.

“Just the one,” the General said, smiling.

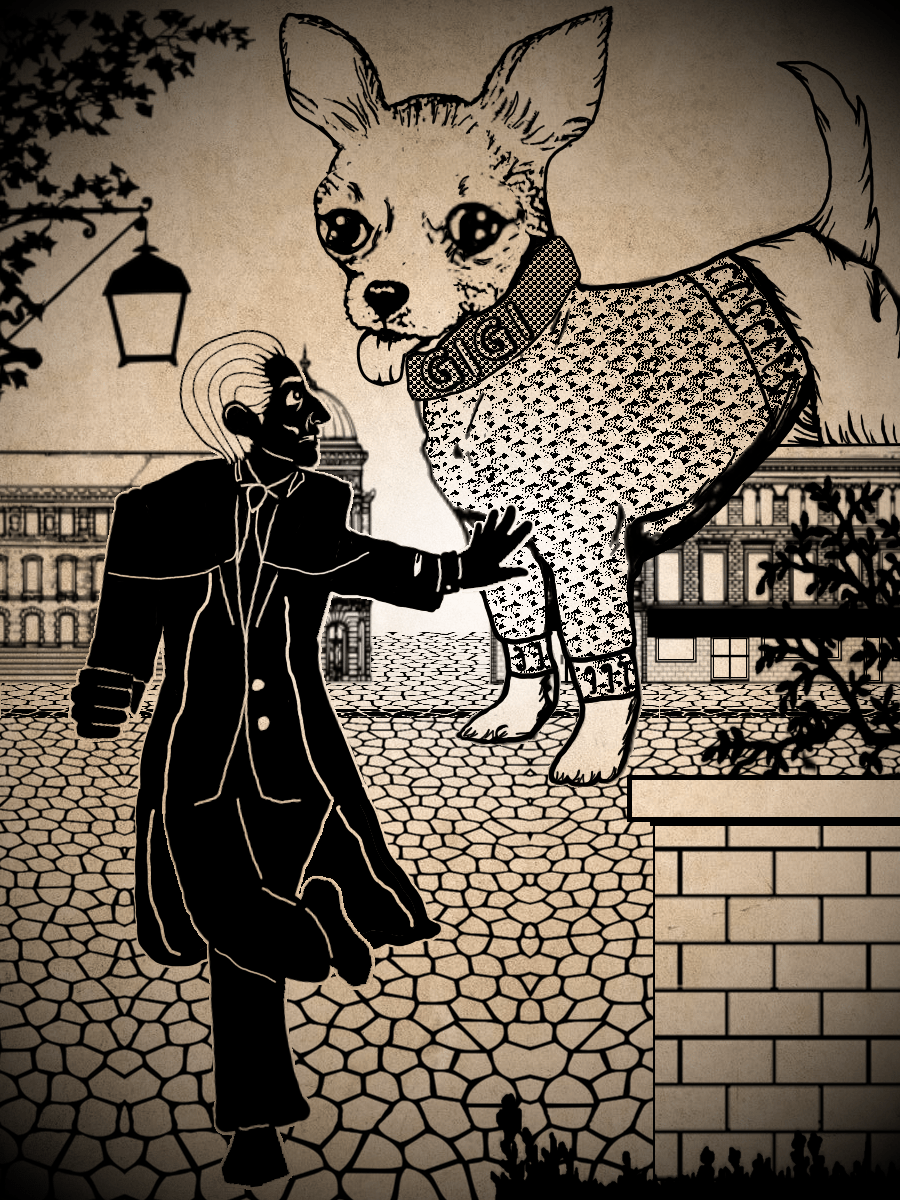

On the way to the bus stop, they came within three paces of an impeccably coiffured woman who was walking a small rat in a sweater on a leash. Except it was not a rat. It would have been all right if it were a rat. It was a dog. Mordecai would have known to cross to the other side of the street — if he were looking where they were going or trusted to make those sorts of decisions in his condition.

“Get that thing away from my Gigi!” the coiffured woman snarled, snatching up her Gigi and putting it directly next to her face.

Mordecai made a valiant effort, but managed to get only a half-step away before knocking into Hyacinth.

Gigi promptly bit its caretaker on the nose and, when dropped, took off running down the nearest alley, dragging its glitter-encrusted leash behind it.

“Ow! You little bitch!” the woman cried, before quickly amending, “Gigi! Mama is sorry!” and running off after it. In heels.

“No dogs,” Mordecai informed the two women beside him. It was written on the side of the damn house!

“Sorry,” Hyacinth managed. She was uncertain whether or not this was funny. It was certainly annoying.

“Walk faster, sometimes they come back,” Mordecai said.

“What could you possibly be afraid it is going to do to you?” Hyacinth said.

“I don’t know!” he snapped. “But haven’t I had enough done to me today?”

“Quite so,” the General said, quickening her pace.

The bus ride home was uneventful. There were no dogs allowed on the bus. Mordecai kept touching the staples Hyacinth had put in his cheek. (She’d used a penny.) Every time he did it, she’d pull his hand down.

Finally she tsked and said, “Listen, it’s swelling and he is going to notice it. We’ll just tell him it was stairs, like you said.”

“That’s not comforting,” he said.

“I wasn’t trying to be comforting, I was trying to get you to leave it alone. Now leave it alone!”

He was disheartened enough to leave it alone.