Mordecai had the violin tucked under his arm. He gestured at them with the bow like a stern schoolmaster. The expression and the three-piece grey suit also fit the part. The surroundings — Hyacinth’s front porch, with its puzzle-piece paint job and smashed-bottle window treatments — did not.

Altogether, it looked like one of those surreal cartoons that tried to piggyback off of Yellow Submarine in the late forties. Pepperland was very progressive and had people of all colours and patterns in it — not unlike Hyacinth’s house.

“This is a sacrifice on my part and I am not doing it unless you all hold up your end,” the red man declared. “The baby has no idea what we’re doing and is exempt.” He indicated Lucy with the bow. “But all the rest of you history buffs.”

Calliope held up the baby and danced her gently. Lucy beamed at her mother and twined a pudgy fist into her dangling dark hair, which Calliope was willing to allow — as long as there wasn’t too much pulling. “She’ll probably yell anyways, Em. Lucy likes fun. It’s too bad Ann has to go to Milo’s job and they don’t have bruises anymore, they like fun too…”

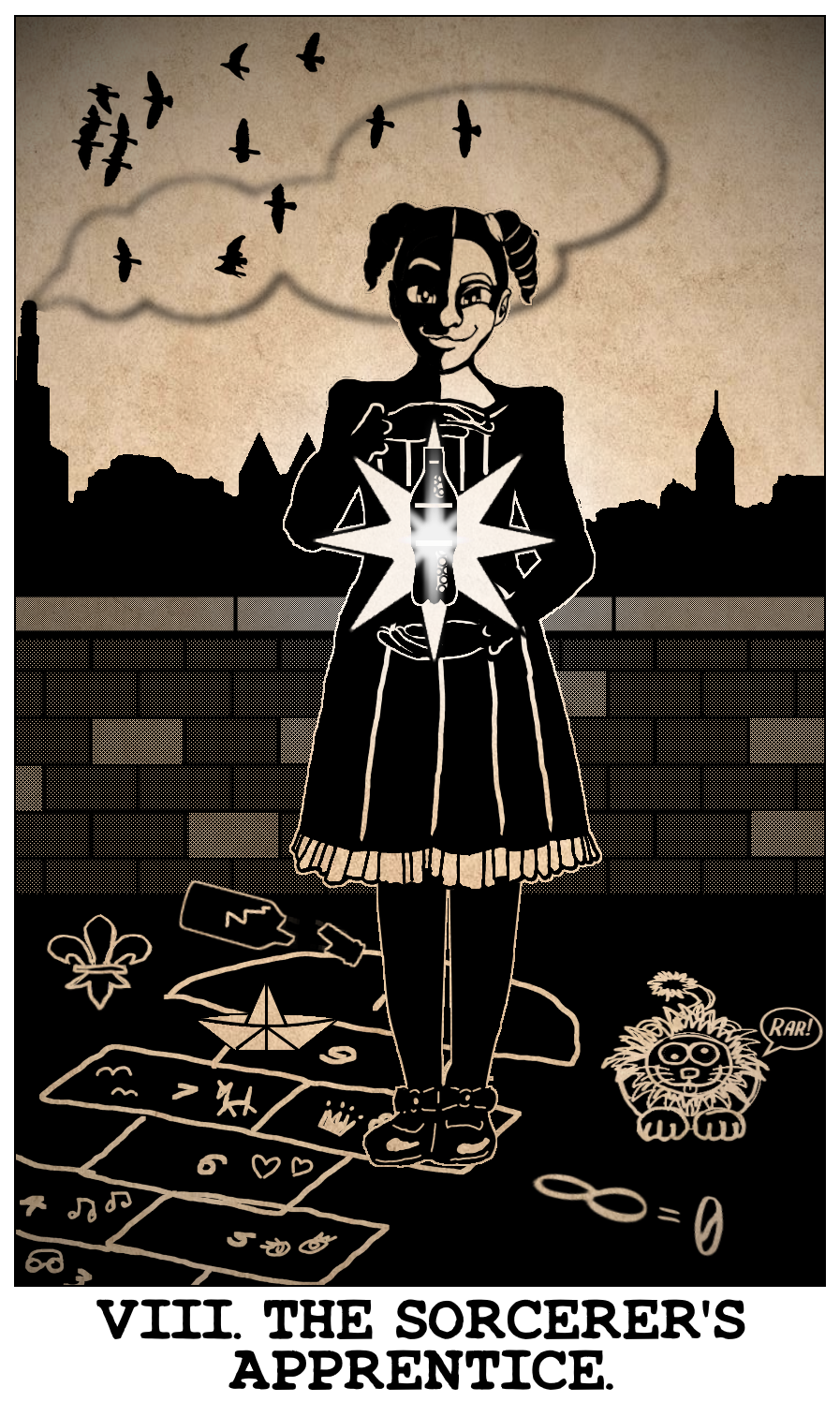

“Shh, Calliope, I’m supposed to be having a lesson,” Maggie said.

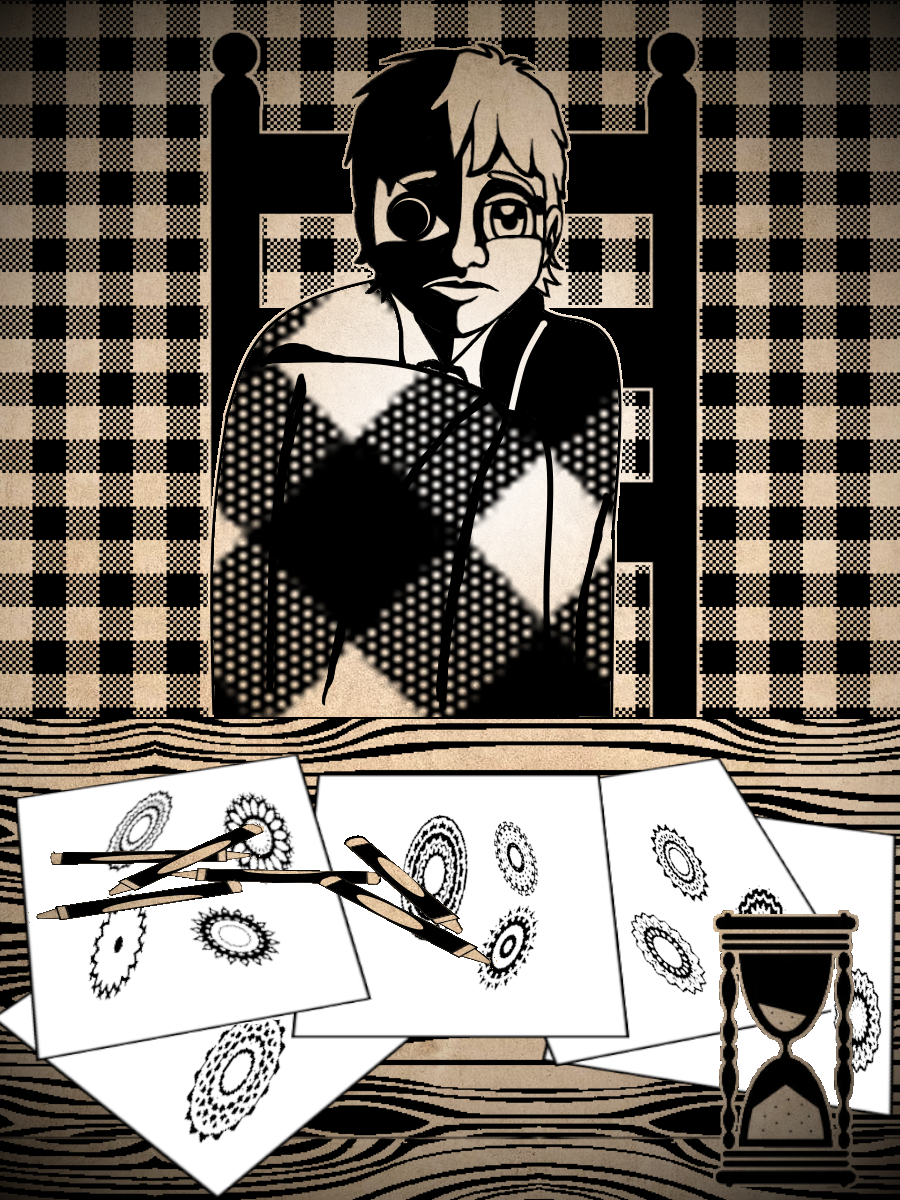

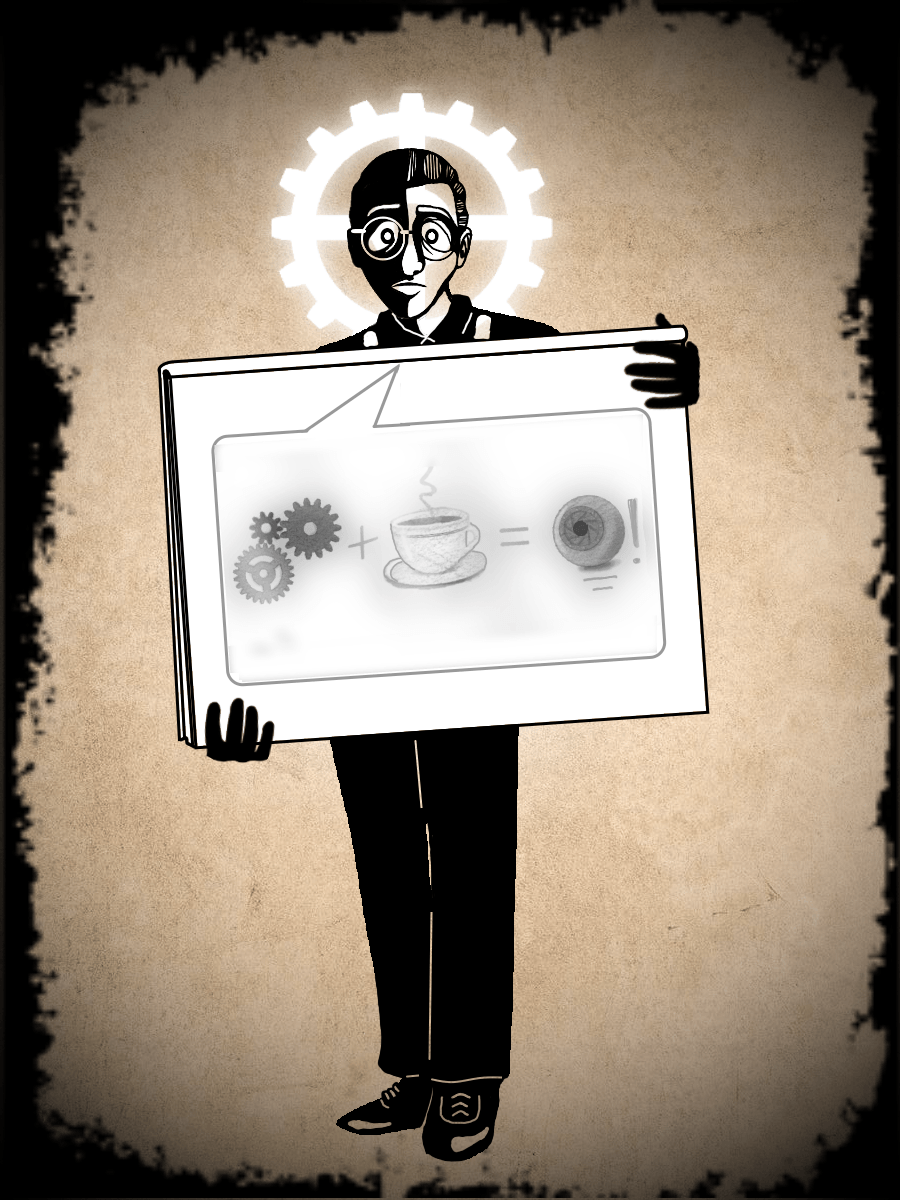

“‘Learning can be fun,’” Erik said tightly, tongue quite firmly in cheek. He rolled his metal eye back in the socket but he couldn’t quite get it to do the full 360°. He was practising in the downstairs bathroom mirror; he thought it made him look extra sarcastic, when he got it right.

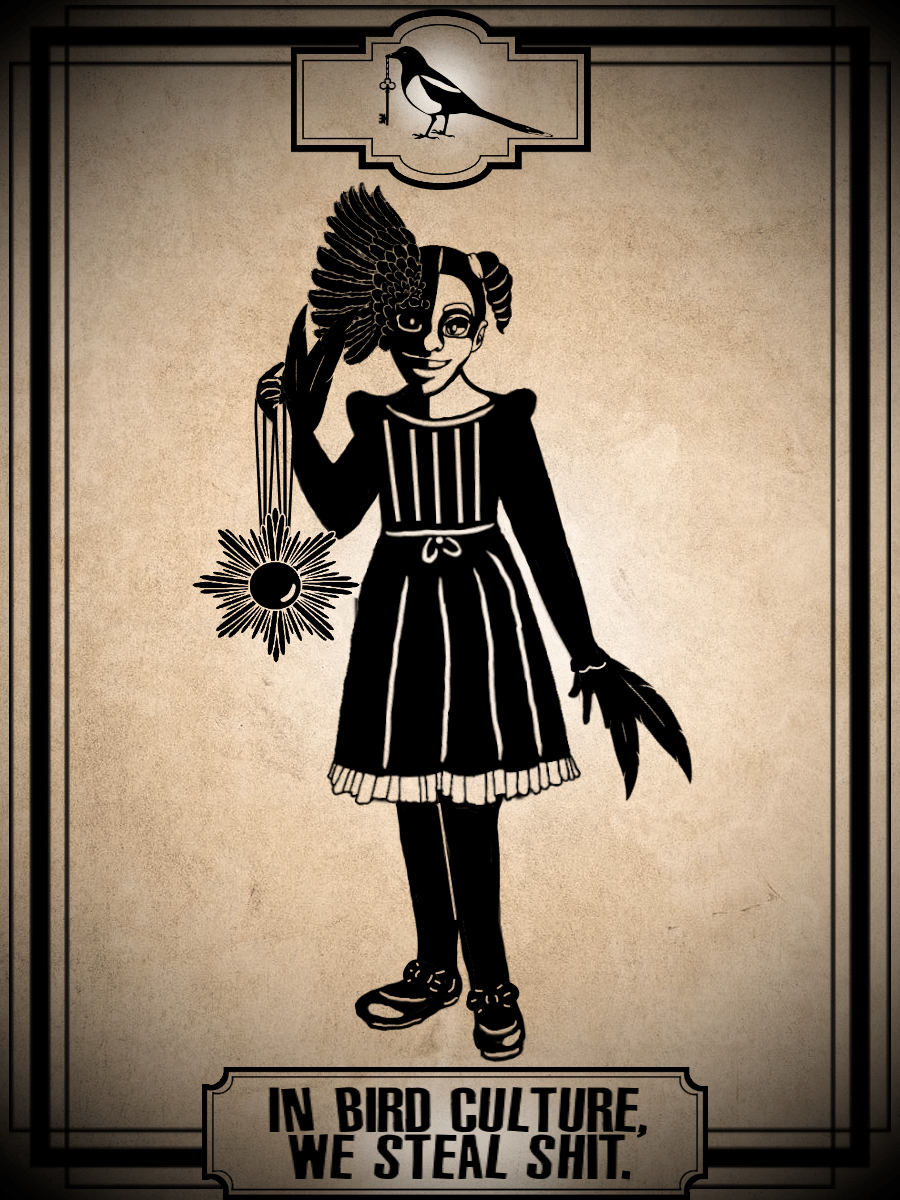

“Yeah, but my mom barely thinks your uncle knows anything anyway, so let’s not push it,” Maggie said. She straightened her dress, and brushed back her twisted pigtails, trying to look neat, responsible, and education-ready.

“…I’ll try to remember it for them so you don’t have to play it again,” Calliope said.

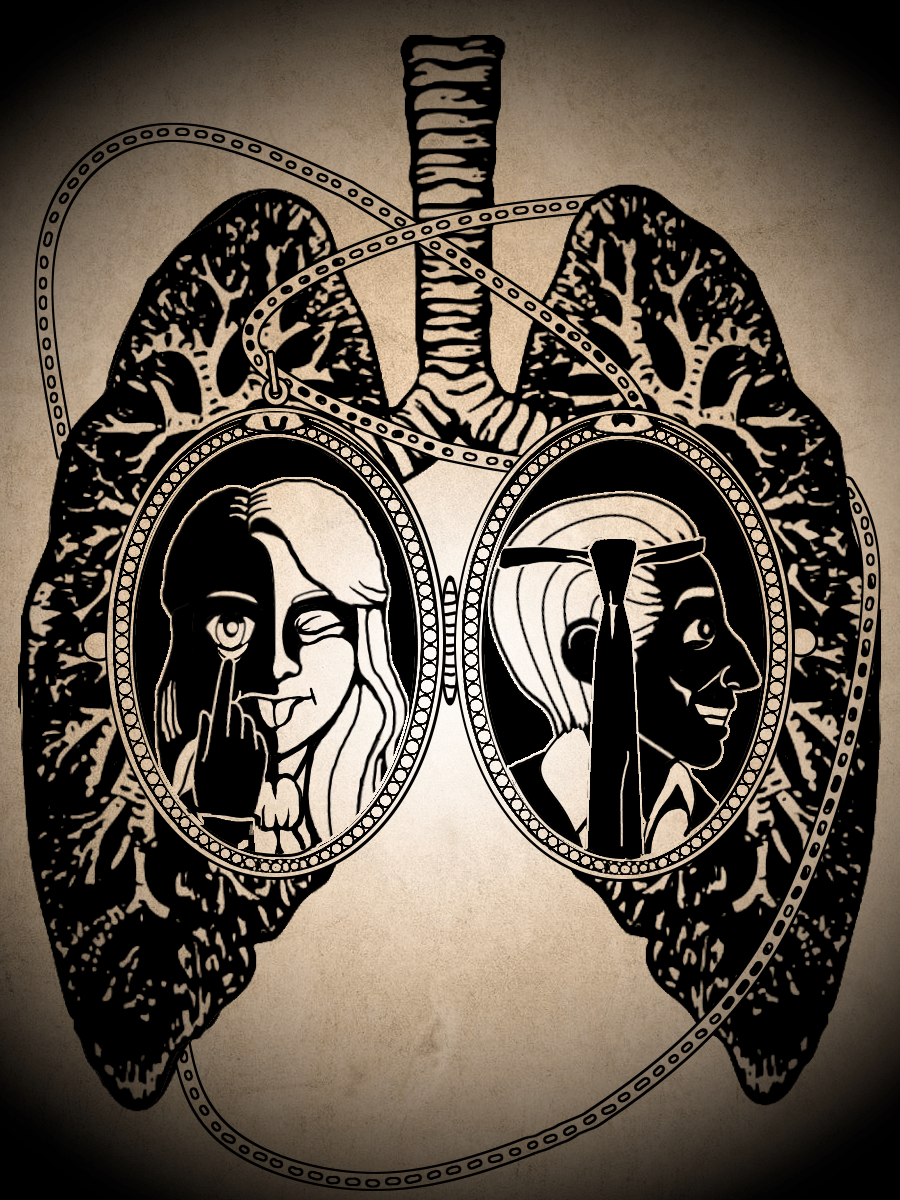

“I’m just here to watch you make a fool of yourself,” said Hyacinth. She was still wearing her leather apron and her goggles were holding back her crispy blonde hair. She only intended to stay long enough to find out some new information to tease him about, then it was back to the decoys in the basement.

“You first,” Mordecai replied. “Remember now, we are not saying ‘fish.’ It’s a substitution.” He grinned. “For concert venues and polite society. And I know all of you know what I mean without my saying it because you live in Strawberryfield and I have no illusions. So say it like you mean it.”

Calliope spoke aside to Hyacinth, “Are we actually supposed to say ‘fuck?’”

“I think it’s like when your polite old auntie switches halfway and says ‘fudge,’” Hyacinth replied.

“Oh, ffffish,” Calliope said.

Mordecai lifted the hand holding the bow like he was conducting an orchestra. He paused and it wilted somewhat. “Hyacinth, you must’ve been alive and kicking when this got popular in Marsellia. Haven’t you done it before?”

She shook her ragged head. “I think it’s a generational thing. I juuust missed you. David and Barnaby and all their friends always wanted to be young and cool, but you guys were the wrong kind of young and cool. You were poor people. And I was too little to like it on my own, you all seemed old and lame.”

He sniffed. “Well, the newspeople thought we were extremely cool. So did most of the country, I might add.”

“My mom thinks you’re traitors,” Maggie said.

“Your mother was an infant, she has no context…”

“She was five,” Maggie said. She was fast with numbers, she had to be.

“…and you weren’t here at all, so I am trying to give you some!” he plowed on. He lifted the bow again, “Gimme an ‘F!’”

“F!” said the assembled audience.

Mordecai sighed. He tucked the bow next to the violin and waved his empty hand. “No, no, no. Look, we were mad about things. We were young, and a lot of us lost fathers in a war, and it looked like we were going to have another war, and we were sick of it. We wanted them to put the money into peace. But they wouldn’t unless we made them. And we were sick of talking about why we were mad too. We did that a lot.

“The best thing was having a whole bunch of us together and the ability to express that we were mad. You have to be mad first, then you can be happy you get to almost say a bad word about it with a lot of other mad people. Okay? I know you’ve all had reasons to be really mad. So let me hear it from you people.” He clenched his fist and raised it. “Gimme an ‘F!’”

“F!”

That still wasn’t great, but it always took a couple letters to loosen up.

“Gimme an ‘I!’”

“I!”

“Gimme an ‘S!’”

“S!”

Now Mordecai was starting to get into it, although it was a bit odd to have the audience up on the stage with him. He leaned into it and cupped a hand to his mouth, subbing for the microphone… which never worked very well anyway. “Gimme an ‘H!’”

“H!”

“What’s that spell?” he demanded.

My parents gave me away! Hyacinth thought.

That awful Mrs. Danvers wouldn’t let me go back for my canvases! Calliope thought.

“FISH!”

“What’s that spell?”

That lady at the hospital didn’t think I belonged to my mom! Maggie thought.

The police punched my uncle in the face! Erik thought.

“FISH!”

Mordecai was bent nearly double by the third iteration and attracting the attention of people walking by on the street — although they just walked faster. “What’s that spell?”

“FIIISH!” the tiny assemblage shrieked with ragged voices. Lucy finished it off with a happy squeal. Noises! Hooray!

Mordecai picked up the violin and began to play. Angie’s voice, somewhat brassy but always flawlessly on key, faded in rapidly and followed along.

“Step right up, young women and men, Marsellia-chan needs your help again! She’s got herself in another jam, way up yonder in Gundaland! So take off your hat, pick up a gun, let’s have ourselves a whole lot of fun! And it’s one, two, three, what are we fighting for? Don’t ask me, I don’t understand! Next stop is Gundaland! And it’s five, six, seven, hurry up and don’t be late! Ain’t no time to say pourquoi, allons à la trépas!”

Other verses extolled the virtue of wars for making money, for military glory, and the status boost you might get among your friends if one of your children died.

Hyacinth, Calliope and Erik applauded. Maggie lifted a finger and spoke gravely, “I believe I detected a kazoo in that, Uncle Mordecai.”

Erik’s smile melted away and he regarded her with horror. Maggie, it’s creepy when you sound like your mom. Quit it.

She just grinned at him.

“It is sarcastic,” Mordecai said. He set the violin matter-of-factly back in its case. “Sarcastic, politically-relevant kazoos are permissible. And very rare, so you’re going to have to go through a lot more history if you want…” He was closing the lid, but Erik had put his hand on it and stopped him.

The green boy looked up with an ecstatic smile. “No… do…” He dropped his head, shook it as if he were dismissing an inadequate clue on a game show, and then sang, “‘Toréador, en garde! Toréador! Toréa…’” He saw Mordecai’s expression and trailed away. “…oh.”

Mordecai managed a weak smile. He shook his head and closed the case. “It’s not your fault, dear one. They always tell you just enough to be upsetting. I don’t play that anymore, that’s all.”

“What is it and why don’t you?” That was Hyacinth. Hyacinth gave less than two farts in a hurricane about being upsetting.

Mordecai sighed.

“Carmen,” Erik put in. Then he shook his head again. It was too complicated. He didn’t even know words for a lot of that stuff, nevermind trying to find them so he could say them at a reasonable speed. The music trick was no help when he had no idea what to say.

What do you call it when you didn’t like something even when you did like it?

Mordecai put a hand on Erik’s shoulder. “I’ll tell her, dear one. You don’t have to ask them to tell you, I know they aren’t nice about it.” It also wasn’t very nice of them to dump a whole lot of upsetting information on a little kid who had a real hard time talking when he was upset, in his opinion.

“It isn’t Carmen,” he said, “it’s Carmen Jones, but we sang it both ways at first because Bizet was our guy. Carmen Jones was in theatres when we started the revolution. It got here later than everywhere else; there was some mixup with the copyright. I learned ‘The Toréador Song’ from there because that was my weekday job. But it was called ‘Stan’ Up an Fight,’ about a boxer who won’t give up until the bell rings, because Oscar Hammerstein rewrote it.

“It was in Music Vox,” he added, for Calliope’s benefit. “We adopted some of it. That would’ve been enough to make me not want to play it anymore, but when we were holding the wall during the siege, Diane got it out of me how I used to play it and it got adopted again. Everyone preferred Bizet to Hammerstein that time, it seemed more appropriate.”

He frowned thunderously. “We didn’t like the Third Coalition Anthem. They didn’t even bother to write us real music — they cribbed it off a cartoon. It was like they didn’t care.”

“So you cribbed some more off an old movie, which they cribbed off an opera,” Hyacinth said with a smirk.

He scowled at her. “At least we got to pick!”

Calliope politely raised her hand, as if in school. “Was that the Diane you wanted to yell at and shake sometimes?”

“Yes!” he snapped. “But I…” He caught himself and shut his eyes briefly to work his way out of coping-with-Hyacinth mode. He tried a smile. “I’m not going to say I never did, but I usually didn’t. It was a stressful time. And she bit me.”

He held up his hand, although you couldn’t see the scar. Erik knew it was there, he had felt it and asked about it.

“She apologized for getting the whole wall to sing Carmen,” Mordecai said, with all fairness, “but she always maintained it was my fault she bit me. And she was the Prime Minister for a while.”

Maggie stood up and waved both her hands like she had left her history book in the back of the bus and it was driving off without her. “Wait a minute, wait a minute! The Diane you know from the war is Diane Desdoux?”

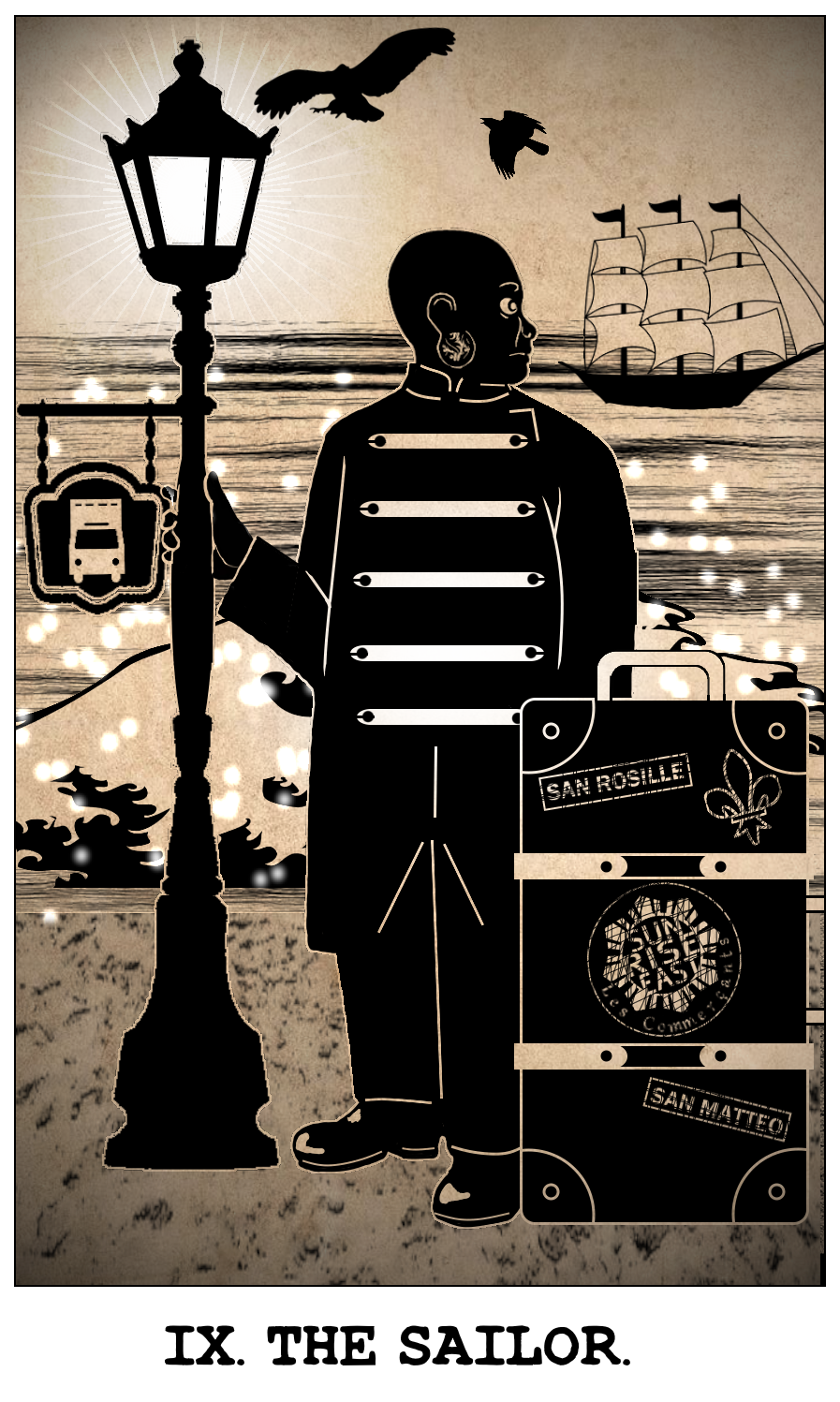

“Maggie, you must know by now that she stayed in San Rosille and held the wall during the siege,” Mordecai said. “I know your mother doesn’t care about me helping out, but she must’ve mentioned the Prime Minister once or twice. She’s on the Empire Quarters.”

Some of those were still in circulation. A hundred and fifty years an Empire, so here’s some cute money with a retrospective of our Emperors, Prime Ministers, and territories. The territories are on the disme, please try not to pay too much attention to the fact that we’ve lost all of them but two. Collect them all! Including the smiling and somewhat embarrassed (Mordecai thought) image of our first coloured PM! And it’s a woman! What a blow for equality!

“It’s a big wall and there are a lot of people named Diane!” Maggie cried. “Also, you barely talk about this stuff! For gods’ sakes, why didn’t you ever tell my mom?” She snatched his arm and yanked him towards the stairs. “Let’s go find her right now so I can see the look on her face!”

Mordecai took her small brown hand by the wrist, shook it to disentangle the fingers and removed it with an acid frown. “Diane is not a valuable object I collected, she was a nice person I happened to know who only wanted to help and didn’t deserve what happened to her. I am not going to get on a bus just so you can use her to annoy your mother, Magnificent.”

“Well, she’s dead, isn’t she?” Maggie said. “What’s the harm?”

Erik socked her in the arm.

She rubbed it reflexively, though it didn’t hurt much. “What? It happened in 1371! Are you still sad?” she demanded of Mordecai.

1371, thought Hyacinth. She remembered reading about it in the paper. They got the whole Desdoux family and burned down the houses. The dissident movement broke up in one night, and they surrendered the next day.

“Oh, my gods, Seth has a southern accent because he’s a rich snob with an estate in South Hestia like me!” she cried. “He’s living under a bridge with an assumed name so they don’t shoot him!”

She swatted Mordecai on the shoulder and he cringed. “Why didn’t you tell me your dead friends were famous? I trapped our first coloured PM’s only living relative in my basement for a week. We could’ve been talking about shrimp forks and fox hunts the whole time. Je me sens idiot!”

Mordecai lowered his head and hissed at her, “Please review the thing you just said about people wanting to kill him and lower your voice, you fool. Nobody needs to know about his family and I hope everyone who just heard you shoot your mouth off will respect that.”

There was silence for a moment.

“You don’t really have an estate,” Maggie said.

“I do and I don’t,” said Hyacinth. “David left me it, but Barnaby had the paperwork and I’ll never find it. I haven’t been back since my father died. I don’t want it anyway.”

“Not even for vacations?” Maggie said. “Why don’t you sell it and rewire the house with the money if you don’t want it? What is wrong with you?”

Hyacinth opened her mouth, but Calliope stepped in between all four of them, holding Lucy against her shoulder. There’s a lady with a baby! Stop shooting! “You guys, that’s enough dead people stuff. Everyone’s got someone or something that’s gone and they’re sad about, and we don’t need to hear about it to do history. Stop being so specific.”

“I am appalled it needed saying and grateful you said it, dear,” Mordecai said. Erik frowned and nudged him.

“Oh, I know you wanted to, dear one. It’s why I didn’t mention anything about no hitting.”

Erik smiled.

“If dead people are off limits, I don’t know what the heck you’re going to teach me,” Maggie said. “Your life is wall-to-wall bodies. You have been in two wars. I have to produce a paper on this.” She pointed a finger at him, “You are being very irresponsible with me!”

“The Cut-Flag Revolt was not a war,” Mordecai said. He shook his head. “It was a mistake.”

“My mom makes mistakes all the time! In wars! And people die! She doesn’t hide them, she teaches me about them!”

“She doesn’t admit them,” Mordecai said acidly.

“My mom doesn’t like you and she doesn’t think you’re capable of learning,” Maggie said. “You don’t know her, and it’s on purpose.” She narrowed her eyes. “When we screw up, we analyze. What do you do?”

“I either pitch it out, scrape it off or paint over it,” Calliope said contemplatively.

Hyacinth lifted a hand and volunteered, “I walk away like I have no idea who did that and it wasn’t my fault. It works pretty well.” Hence her reluctance to reclaim her estate.

“No, it doesn’t,” Mordecai said. “Nobody else in this house burns noodles and leaves them for me to clean up, I know that’s you.”

“Prove it,” Hyacinth said.

Erik raised his own hand, “I feel bad.”

“That is appropriate and so do I,” Mordecai replied.

Maggie folded her arms. “Well, Calliope and me and my mom are the only people who do anything about fixing it.”

“I am constantly fixing things in this house!” said Mordecai.

“So am I!” said Hyacinth.

“Other people’s stuff, not your own,” Calliope said. “But you clean up after each other, so it works out.”

“Ha!” Maggie accused.

“Nuh-uh!” said Hyacinth.

Mordecai took a few paces away and leaned on the porch railing, gazing into the yard.

“Why don’t you teach us, Maggie?” Hyacinth said. She sat down on the uneven planks and crossed her legs at the ankle. “Since you seem determined to take me to school. Go on.”

“No,” Mordecai said. He gently brushed Erik aside. “I said I would do this. You asked me so you wouldn’t have to go stand in line all day to watch your mother set a government worker on fire, but I agreed to it if I got to tease you first and we’ve done that.”

He drew a breath, and instead of sighing, he spoke, “The Cut-Flag Revolt began in the winter of 1343. It was a Frig’s Day and the weather was nice. If it had been snowing, we might’ve put it off for the spring. We’d already had the flags for some time by then, but the uniforms came after — we wore black with a red handkerchief and a white rosette. Because nobody had money for anything fancy and we didn’t want to shoot each other by accident. That was after the shooting started.

“When we marched uptown to the Chambres of Parliament, we only had the rosettes. I think Gen… This girl I knew brought them. She worked in a dress shop, part-time. Or they might’ve been wedding favours. Anyway, they were in two big bags and we took them with us and handed them out on the way.

“We walked up from Strawberryfield. We had a lot of signs about things we were mad about, and we had our Declaration of Intent, which we’d managed to edit down to two pages printed on both sides, but we made lots of copies and handed those out too.”

Now he allowed the sigh.

“Diane Desdoux, who would later be assassinated ahead of the Marselline surrender in 1371, was working in a law office downtown at the time. She saw us, but she was much too responsible to take a rosette and go protest. Later, she told me she regretted it. I believed her, but she was old for it and I understood.

“I was old for it too — I was twenty-four and I’d already been married and divorced, and I had two jobs. Most of the others were still in school, and I worked nights, so we had afternoons off and lots of time to stay up talking about changing the world.”

Maggie raised her hand and interjected, “Four Square University, which had been operating in San Rosille for seventy-five years, moved its main campus to Ansalem in 1345, and closed the extension in San Rosille in 1353, due to low enrolment.”

“I’m sure you’re capable of connecting the dots, Magnificent,” Mordecai said. “They also raised the drinking age in public houses and bars in 1344, by a special Act of Parliament.”

“Was that your fault?” said Hyacinth. “You’ve been annoying me since before I knew you. David wouldn’t even buy me a fake ID, he said I should practice lying or go to an arcade.”

“Milo is twenty-four in May,” Calliope said, frowning. “Milo should not be in charge of a revolution.”

“Oh, gods, no,” said Hyacinth.

“What about Ann?” Erik said. Ann was way better at being in charge of things, so Milo usually got changed and let her.

Calliope nodded. “Oh, she could if she had to, but she wouldn’t like to.”

“It was very much like that,” Mordecai said. “Except we didn’t think we were going to have one of those revolutions with barricades and people dying in the streets. We thought we’d just talk to them about it and they’d behave rationally. We thought we were being responsible, a voice of reason. Of course, by the time we got uptown, there were a couple thousand people following us, and Château LeRoux wouldn’t let us in.”

He frowned.

“We did not start it. I cannot prove that, but neither can they prove we started it. The gun laws were very similar back then, although the farms and rural areas were closer. Private citizens required a permit to carry within city limits, and the police have to go back to the station house and sign one out if they want one, it’s still like that… but Imperial Guards are armed, and there happen to be Imperial Guards in and around the Chambres of Parliament.

“I think somebody thought they saw something. There were a lot of people and we had angry signs and we were getting louder the longer they made us stand out there in the courtyard. We invited the city to come with us and one of them could’ve had a rifle or something, but I suspect it was magic they saw. Anti-magic was… basically impossible back then, and countermagic can’t be automated. Someone saw magic or thought they saw magic and they got scared.

“I didn’t realize… I don’t think anyone realized we were going to have a violent revolution until the shooting started.”

He turned towards Maggie and folded his arms, “When your mother teaches you about the Cut-Flag Revolt and all those traitors to the Empire like me, does she mention anything about a load of Imperial Guards firing into a crowd of unarmed civilians? They were lined up on the roof. It was very difficult to hear with all the screaming and running around, but I believe I discerned a repeated command to fire. It was politically-relevant, but not at all sarcastic.”

“She said you shot a clerk,” Maggie replied dully.

“A clerk was shot, through a window. I cannot guarantee you that someone we brought with us did not do that, but there were twelve of us when we started our march up from Strawberryfield and a couple dozen more waiting around the bar on South Hollister and we did not have guns. We wouldn’t have known what to do with them if we did have them. We had to learn.

“There were also guards on the ground. I think it is more likely one of them turned around.

“I am sorry about the clerk,” he allowed. “I’m certain he was just doing his job, but he survived. Three people outside did not, and more were injured.

“White rosettes with blood on them became fashionable for a little while,” he added, with a shrug. “People would buy you drinks.

“So we broke up and ran. There were not many arrests. I think the police were as surprised as we were. I think the guards were surprised — they didn’t think, they just did what they were told

“I met a couple people who got arrested, later. They joined up with us. They said they just got put on a twenty-four-hour hold and let go — they didn’t have guns and nobody could prove anything. Some of us hid in houses and stores, some of us just went home. Pa… A boy I knew said he panicked and tried to hail a taxi, then he realized how stupid that was, ducked into an alley and threw up in a trash can.

“But later that night, much later, we came back to that seedy bar on South Hollister where I used to play ’cello for a cover band.”

“It was called Marie Roget’s and they were operating unlicensed gambling too, ” Maggie said.

Mordecai nodded. “In the back. There was a hidden room. We thought we’d be safe. I brought that subversive little book on urban warfare — which I no longer want, Maggie,” he told her. “And some of the others brought guns. Which, fortunately, that subversive little book had directions for operating.

“We went door-to-door and claimed territory like a street gang. We turned up some of our friends who were hiding, and a lot of others joined us. People don’t like being shot at by their government. We evicted the ones who didn’t want any part of us, as kindly as possible. We took their furniture for barricades — and we took their money, we needed the money — but we left their photos and personal things alone.

“We made more signs — we wanted everyone to know why we were doing it. The papers and the newsreel people had a field day. We even had our own embedded reporters. They published our Declaration of Intent. We were thrilled. We thought they were helping. Like they cared.

“Because of the signs and the newsreels, we had kids all over Marsellia taking to the streets to support us. And, I think, some in the ILV. They made signs, too, but they learned from our mistake and they didn’t go unarmed.

“We didn’t have the capacity to coordinate with them, we just read about them in the papers like they read about us. We were glad, though. We thought we’d really accomplish something. Maybe we could go worldwide like Hennessy’s and have a war to end all the wars.

“We were stupid like that.

“They tried to arrest us and we wouldn’t let them, so they fought us. It was dirty and awful. We were not soldiers and there were no treaties to protect us. We were criminals. Terrorists. They didn’t take prisoners — when they caught us, they shot us. To be fair, we did manage to liberate many of the police stations and take their guns, so it wasn’t like they had anyplace to put us, not in the city.

“We did eventually get into Château LeRoux. The government had been operating out of South Hestia for months by then, but we got into the building. We did some light vandalism and threw papers around… We were mad, I did mention that. I carved my initials into a banister leading up to some offices on the second floor. Diane told me they were still there, but she always thought some woman named ‘Mae’ did it. The ladies’ toilet was up there too.

“Since there was nobody there who mattered, we read off our Declaration of Intent on the floor of the Chambre Grande and elected our own government. They wanted me to be Prime Minister but I declined. Diane always thought that was absolutely hilarious and she accused me of making it up to amuse her. I took a lesser office of Representative of the Magical Community and Associated Interests, which we thought we needed and made up.

“There may still be newsreel footage out there of us kids playing at fixing everyone’s problems. We passed some tax laws. It didn’t take us long to get bored of it. We couldn’t enforce anything and people were shooting at us. We painted some slogans on the façade and left Château LeRoux alone.

“We thought, we honestly thought, if we could just claim the whole city we’d only have to defend the existing walls and it would be easier.” He twitched a bitter smile and shook his head. “We thought holding the wall would be easy. Then we could start doing policy like we wanted in the first place.

“We tried to collect taxes and help anyone who needed it but, you know, people were shooting at us. We sure as hell couldn’t repair the roads and invest in public transportation. We did try giving people free bicycles, but the roads…”

“Oh, my gods, you were dumb,” Hyacinth said. “I mean, David and all his friends always said you were being silly, in a cute way, but I never suspected you were dumb. Not you.”

He shrugged. “I admit it. We were young, and we didn’t want it to happen that way. Once the newspeople showed up, we had an audience and people following us. We felt responsible for them. So we stood up and fought like hell.

“Most of us — the core group of us, the band and the people who used to come to the bar and listen — were hearing the bell by summer. But we kept going because of all the people watching us. We thought maybe even if we couldn’t do it, they could. Or all of us together. But we were getting killed out there, every day, and the people following us were too.

“There was a raid in Valle del Mar… That was a little town north of South Hestia. The people there managed to take over the whole place and start doing some of our policies… there were a few little towns like that. We were proud of them. But Valle del Mar was near where the government was operating, so I guess they were more worried about that. They killed everyone wearing black and they burned the place to the ground.

“We read about it in the papers, that was on the 30th of August.

“We surrendered… We didn’t surrender. We weren’t soldiers, we didn’t get to do that. We gave up on September second. We didn’t turn ourselves in or anything, we just told the newspeople it was over and to go home. We made a decision there would be no speeches. We didn’t want there to be any more fighting… Not like your mother, Maggie. We waited until the second because we thought it might be a little harder to remember than the first.”

“You missed my fourteenth birthday by one day, so I never forgot it,” Hyacinth said.

Mordecai shrugged. “We hoped most people would forget it, but at the time all we wanted was for it to stop. We had to keep telling them. They wanted us to give them more story. It was like they were demanding it. They were nice to us, they were our friends, some of them died covering us, they were entitled. But there were few enough of us left that we decided what we wanted to say and we stuck to it and they had to report it. They didn’t get any dissenters, not in San Rosille.

“Some kids in other places said they’d keep going without us, they gave some speeches and the newspeople covered them, but by fall’s end they had all stopped. So it really was our fault it went on as long as it did.

“We did our best to disappear… Most of us managed it. The people who were watching saw uniforms and signs, not individuals, and there were just too many of us. You couldn’t tell who’d been leading it and who was just going along. Every once in a while I think I recognize someone, but I don’t bring it up and neither do they. Those of us that survived have lives now, we don’t want to ruin it for each other. I don’t talk about it, and I try not to use names when I do.

“Everyone wanted to forget. We let them, and they let us. We were ashamed for standing up and getting people killed by being dumb, and they were ashamed for killing a generation of their own kids who were just being dumb. That’s why the history books are somewhat lacking and you have to hear it from a person who was there and who’s willing to talk, Magnificent.”

“You don’t really know who started it,” Maggie said, frowning.

“No, but does it matter?”

“Well, you…” Maggie waved a vague gesture. “You factor it in…”

“Ah,” Mordecai nodded. “You’re trying to figure out who the good guys were. You probably won’t believe me now, but as you grow up you’re going to realize sometimes there aren’t good guys, or bad guys. Most people are just trying to do the right thing — but that looks different depending on where you’re standing and sometimes you can’t see it at all.”

“Be the first one on your street to have your child sent home incomplete!” Erik burst out suddenly. He clenched his hands at his sides and spoke with a furious, twisted expression, “People aiming guns into a bunch of other people who are singing and waving signs around know they are not doing the right thing! They could see it from the roof where they were and they did it… anyway!”

Mordecai startled and cringed. Oh, gods, I forgot about that person who gets random updates from the gods and who is eight years old and whom I love…

He was just trying to hurt Maggie by giving her more information than she required! And, in retrospect, that was also stupid and evil on its face.

“Erik, they…”

“They had orders,” Maggie said. But she didn’t look terribly convinced either.

“Don’t ask me I don’t understand! Next stop is Gundaland! They pulled out that man’s fingernails and they shot him in the head!”

Mordecai wheeled around and glared at the empty air above them. “Okay, who the fuh…” He glanced at Lucy and Calliope, whom he had also semi-forgotten. “Who the fish is floating around out here making me explain the concept of torture to an eight-year-old? I left that out on purpose! What the hell is the matter with all you invisible people?”

Erik frowned. “Hester Carthage says she’s… sorry, but it’s harder to… throw them out when they’re not in the… house. Five, six, seven, hurry up and don’t be late. Maggie and me saw it in comics already. The bad guys do it to get you to talk. The bad guys.”

“What about when Puma Man flies a guy up in the air and drops him a whole bunch of times while asking him questions?” Maggie said.

“It’s okay if you know they’re bad!” Erik cried.

“Well, now I know I need to start vetting your comics,” Mordecai said weakly. He knelt down and put hands on Erik’s shoulders. “Dear one, the only people who do things like that are bad or stupid. It doesn’t work like in the comics… Or movies. Or pulp novels. Or serials. Or cartoons…” He blinked as if stung. “My gods, no wonder people think it works.”

He shook his head. “Listen, when you’re hurting someone or they’re scared you might hurt them, they don’t tell you the truth, they tell you whatever you want to hear. Some of us were… Some of them did that to some of us trying to find out where the rest of us were. And… and it didn’t help anything. We only found out about it because a couple of us escaped before they got shot. We told the papers. Not that that helped, either, but…

“But I’m getting away from it because I don’t want to talk about it,” he said, all in one rapid breath. He nodded once to himself, and spoke firmly to Erik, “Nobody ever did that to me, and I never did that to anyone. We didn’t do that. We knew it wouldn’t work. They… They got desperate and they tried it.”

“You weren’t the bad guys,” Erik muttered. “That’s… worse than… pointing a… gun at a… lady and making her pack a… suitcase while she’s… crying.”

Mordecai winced.

The wallpaper had been bright green. Bright-green wallpaper of a particular shade called Kew Green, which he’d learned to identify and boil for the arsenic content during the siege. The weeping woman had claimed to be pregnant. Sometimes he tried to tell himself he’d done her a favour, because of the wallpaper. Her hands were shaking and she kept dropping things. He’d gotten it into his head somehow that she was doing it to annoy him because she didn’t want to go and he’d finally screamed at her, Leave the stockings! You can buy more stockings! Just get out of the damn house!

“Do you know why I did that?” he said.

Erik nodded. People who didn’t want to be in the revolution had to go so they wouldn’t get hurt. His uncle scared the hell out of that lady and kicked her out of her home to be nice.

“Do you know why they tortured that man you saw?”

“I… don’t… like… that… part!”

“Okay!” Mordecai said quickly. He drew Erik near and held him. “I’m sorry. I don’t mean to make them tell you more things and I didn’t mean for them to tell you what they already did. It’s just… Everyone had reasons. We thought — they thought — they were good reasons. But it wasn’t good and it shouldn’t have happened. I might not’ve been a bad guy, but I wasn’t a hero. You know that?”

“…No,” Erik spat.

Mordecai set him back and tried to look him in the eye — which was difficult for both of them. “Hey. Hey…”

He finally touched Erik’s cheek and made him turn. “Listen. I don’t want you to be like me when you grow up. You can play violin and fight monsters, okay, but don’t get so caught up trying to fight monsters that you start doing damage to real people. You don’t have to decide whether what I did was bad or good, but I don’t want you to do things like that. Because it would hurt you. I know that because it hurt me. Will you promise me?”

Erik shook his head and turned away again.

Mordecai sighed. “Maybe that’s a little much to ask right now. Will you try to remember that’s what I want for you? To be better than me?”

Erik nodded.

“Okay.” Mordecai stood and turned away. He drew a deep breath and wilted as he let it out. “Oh, I shouldn’t teach people things. This was a terrible idea.”

“I learned stuff,” Calliope said gravely.

“My mom says when teachers get lazy and don’t pay attention to what they’re doing, they do ‘collateral education,’” Maggie said. “Like collateral damage. They teach bad lessons you have to unlearn later.” She glanced at Hyacinth. “Like ‘it’s okay to hit your kids.’”

Hyacinth narrowed her eyes and considered Maggie with arms folded. “It’s never okay, but very rarely…”

Mordecai raised both hands and stated categorically, “It is not okay to overthrow the government! Nobody learn that! If you learned that, stop, turn around, go back and learn something else!”

Hyacinth considered that too. “I would also say that very rarely…”

“I learned Marsellia used to have a Nation-Tan,” Calliope said.

“Pardon?” said Mordecai.

“It’s in the song,” Calliope said. “I was gonna mention it, but Erik wanted to talk about Carmen Jones.”

“What is a ‘Nation-Tan,’ please, Calliope?”

“A cute little girl who acts precocious and represents you. They say ‘tan’ now instead of ‘chan’ because it’s cuter. Wakoku-tan likes warm hugs and pickled fish. She has a paper fan with the flag on it. And Xin-tan has a little hat and a chow-chow puppy. Chozin-tan has a grumpy face because she got colonized and she’s still mad about it. Don’t you guys read comics from Wakoku? They’re fun. Everyone’s got huge eyes and they look like sad bugs with the bodies of twelve-year-olds.”

“They were printed backwards and Erik and me got annoyed,” Maggie said.

Erik nodded.

“Some of the newer ones are mirrored,” Calliope mused. “Anyway, what was Marsellia-chan like, Em?”

Mordecai laughed. “I knew we got her from Wakoku, but I didn’t know they were cranking out more of them. I thought we were special!”

He framed a small space with his hands, approximating the size of the drawing, as he remembered it. “A comic artist in Wakoku invented her right around the time they sent us another batch of cherry trees for our hundredth anniversary as an empire, and we adopted her. When I was a kid they were still drawing her with a bow and arrows like the original art.

“They reprint that every once in a while, I’ll point it out to you next time I see it, Calliope. She was standing on her tiptoes and hugging the Wakokuhito PM to thank him. Wakoku is ancient compared to us, even if you count when we were a kingdom, so of course they drew us tiny.

“We still have her, we’re just calling her Li’l Marsellia now. She’s a little blonde girl with petticoats and a great big gun. She can’t pronounce her Rs or Ls. That means when you see her in political cartoons she’s usually introducing herself as ‘Widdle Ma’sewwia.’”

“Is it any wonder intelligent people never bother with the editorials?” Hyacinth said.

“There’s… cartoons in the… editorials?” Erik said, blinking. He was missing out!

“Not good ones,” Maggie assured him. “Just a load of old Nation-Tans with…”

Calliope stood abruptly and waved Lucy’s little hand. “Oh, look, there’s Milo! He figured out how to get home! Say ‘Hi, Milo,’ Lucy. ‘Hi!’”

Milo looked up, saw everyone on the porch, paused and took a reflexive step backwards. Oh, gods, Ann, what have I done now?

Milo, I’m sure…

My toaster with three slots blew up and rendered the entire house uninhabitable!

Milo, your toaster with three slots is in pieces and it doesn’t even have a power source yet, it can’t possibly be…

My headphones, then.

You have barely started drawing your headphones, Milo.

My coffee-roasting experiment!

…Okay, that is not impossible and in retrospect we probably shouldn’t have left it going and hid it under the stairs, but I don’t think it’s likely…

…Calliope is happy.

Ann wasn’t sure that necessarily precluded the coffee experiment blowing up, but mentioning it would be counterproductive. Yes, she is.

Milo cautiously set the plywood gate aside and approached the people who might be mad at him for doing something wrong. Calliope ran down the stairs bearing a giggling Lucy (Maybe the Lu-ambulator broke?) and with no shoes on (Oh, no, Calliope, the yard will hurt you…).

They both smiled at him. “Hi, Milo. Hug?”

Milo got a hug. Then he didn’t care so much about the mud and the trash in the yard.

“Do you like old music? Em played us a song from the Cut-Flag Revolt. He hates everything about it and he won’t do it again, but I bet me and Erik can sing it!”

Hyacinth smirked and folded her arms. “So, my condemned building beats out a cardboard box behind a pub for two days running.”

“Is it really condemned?” Maggie asked excitedly. “Don’t tell my mom!”

Mordecai did a slow fade back inside and left the door half-open so no one would notice it closing. It was time to get started on lunch. The lesson was over.

A few moments later, Erik followed him, frowning.

The learning continued, nevertheless.