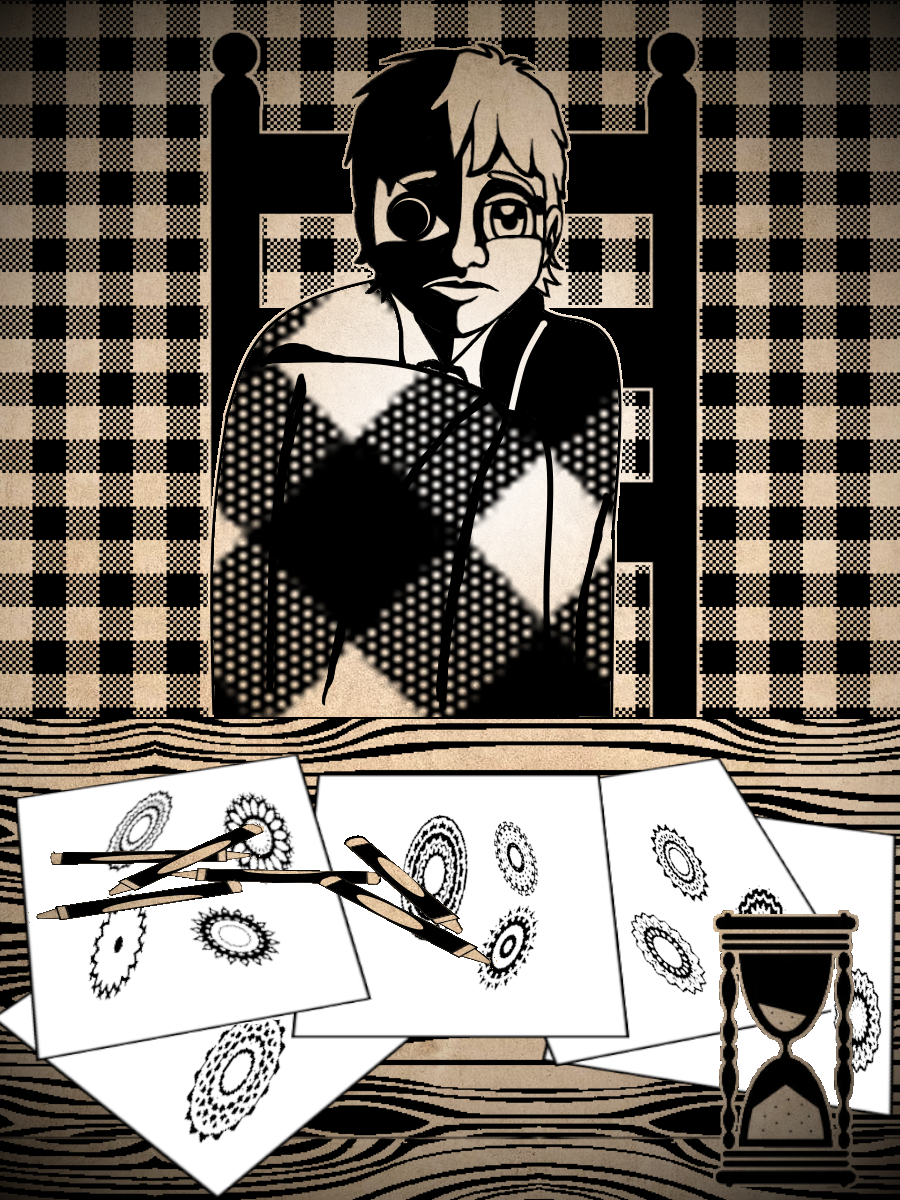

Bird lessons had to be postponed for a few days. Magnificent had been practising on her own time, and it was harder to gain the weight back as a child.

Practising or playing, but playing was a kind of practice. The General had consumed many books on the subject and was a student of nature documentaries, both film and radio, and she was quite sure. It may feel fun for the lion cub to stalk its mother’s tail, but it is learning to kill and that is serious business.

She had also been quite sure that her daughter knew how to play. Attempts at observing what her daughter did when told to go play or given free time for any activity had not been encouraging, however.

The General had spent a lot of time in bird form herself recently, creeping around the house and hiding in closets or under furniture, concealing herself with optical magic whenever possible.

Magnificent appeared incapable of selecting an amusing activity and focusing on it.

Most mortifying of all, Erik appeared to know how to play and kept trying to help her. And for some reason Magnificent refused to take advantage of this educational opportunity.

Excuse me, Magnificent, I have tried to teach you that we can learn things even from people who are foolish or frustrating! (It was a good thing she didn’t have a human tongue in her mouth or she might’ve burst out and said it.) Why do you think I’m always so patient with Mr. Rose?

She had at last decided that her daughter didn’t understand the lesson.

It’s because I don’t know how to teach it, she thought, observing Magnificent abandon a crayon-related activity at the kitchen table from the shadowed cabinet beneath the kitchen sink.

Damn it, if the Captain were home…!

If the Captain were home he’d think she was teasing him. And if she managed to get it across that she was serious, he’d be disappointed in her. You did what to our daughter, sir?

Damn it, why doesn’t my child default to playing? Erik does that! Children are supposed to work that way! Even the street children make toys!

Is it possible I have screwed this up so much it can’t be fixed?

…and I never would’ve noticed it at all. That damn idiot fake-soldier downstairs had to tell me.

She wanted to drag Mordecai upstairs by his one functioning arm, point at him as an object lesson and say, This is what I mean by learning things from people who are foolish or frustrating, Maggie! This jackass figured out I was hurting you and this time neither one of us saw it.

But it wasn’t his fault, and she damn sure didn’t want to make her daughter’s emotional development his responsibility. He might teach her it was all right to cry, or something utterly useless like that.

So! Bird lessons! Because she was bound and determined to teach her child that it was all right to play. Being a bird was much more fun than being a human, and there wouldn’t be all that awkward… talking.

She applied a “show me” to herself and her daughter, and told Magnificent they were going to practice doing magic in bird form. That was a reasonable thing to practice; it was harder to do magic as a bird, without a human voice or human hands or a human level of alma.

She changed first. Because of the “show me,” the blinding white flash was accompanied by a neat spiral of red, white and green light, which corresponded to the complicated magical function of breaking a human body into a bird body and storing the unneeded mass in slipspace. By necessity, this was accomplished in an instant, but the traces of the spell remained in the air like Yule lights on a cylindrical tree, until she waved them away with a wing.

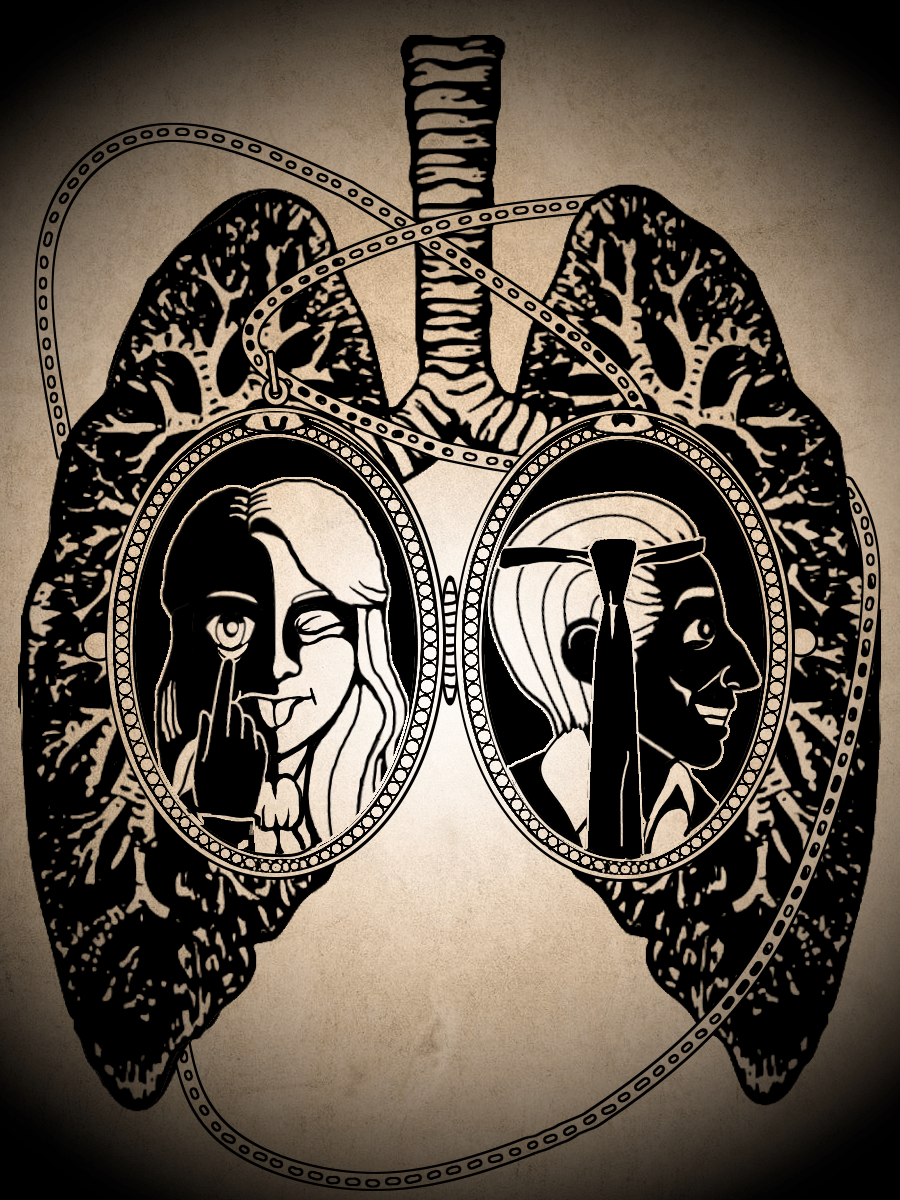

The General felt most graceful in bird form, even if the difficulty of magic while wearing this body made it hard to be at ease. She was aware that she was fat and rather toad-like. Her weight was a matter of national security and she was proud of it. Her face was a matter of heritage and she put up with it. But as far as she could tell, she made quite a handsome bird, only a bit larger than average altogether.

Magnificent, she thought, was an improvement on the standard model D’Iver woman. She didn’t care much if her daughter remained objectively cute, just that Magnificent would retain enough self-confidence as she grew that if anyone ever tried to make her feel ugly, she would tell that person to go commit an anatomically-impossible act in the rudest possible way without feeling even a twinge of hurt.

The General had long since given up trying to feel beautiful or desirable. She knew the Captain wanted her, that would do.

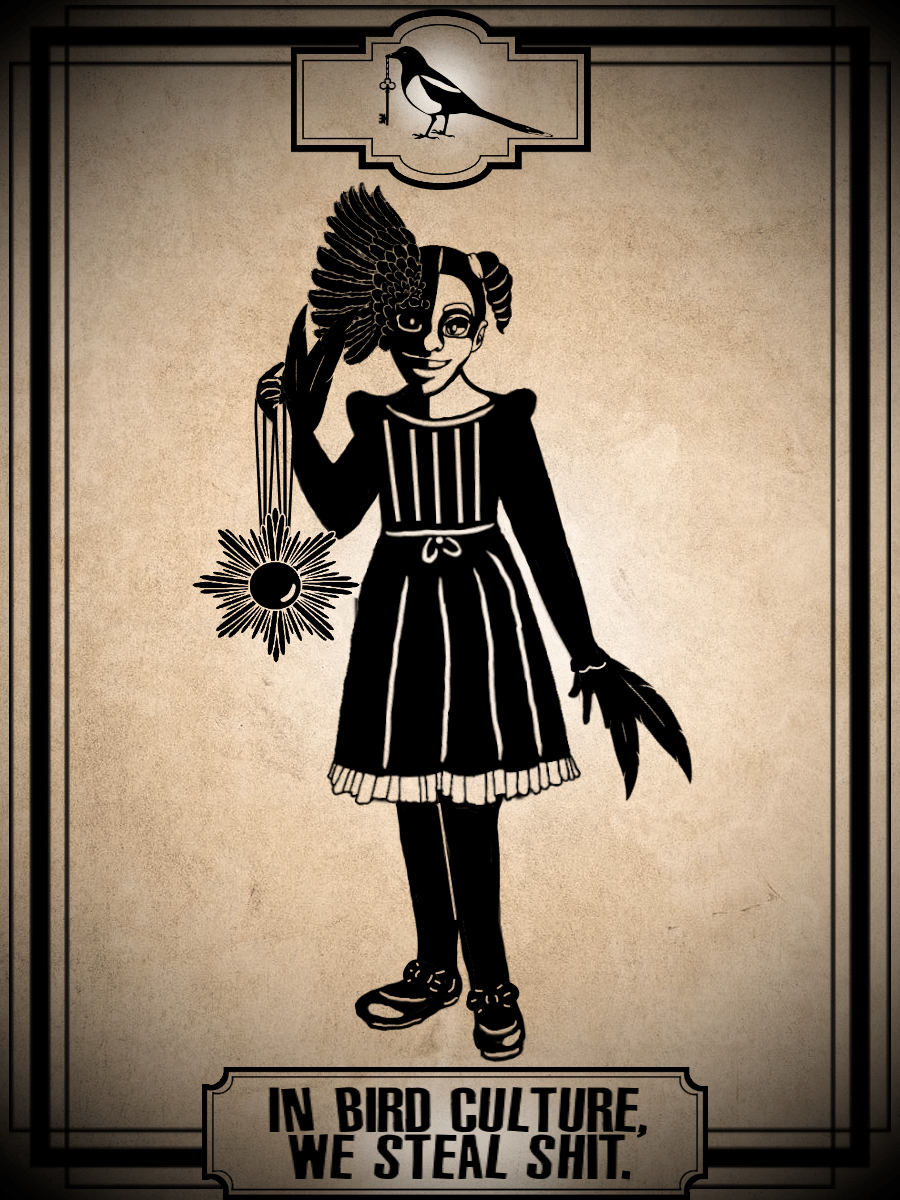

The large golden eagle turned her back to protect her vision. When she turned around again, the black and white magpie was trying to dismiss the visible threads of the spell by crossing her wings in front of her and cutting them aside, as she would do with human hands.

The General waved her wing again and the lights faded.

“No!” squeaked the magpie, sounding as irritated as possible. Her bird voice was like a cheap toy telephone, and much harder to operate.

The golden eagle shook her head and gave a single chirp. She couldn’t speak at all as a bird, everything had to be implied. Not important, Mag-Pirate.

If pressed on the matter, she would admit to learning more than the odd bit of magic from Mr. Rose.

She took off. Takeoffs were most difficult for her — she was accustomed to giving herself a little boost with magic and “show me” also rendered it visible, a white thread bunching and gathering beneath her wings before it faded. It was a momentary atmospheric effect, not like being an entirely different species with most of your body mass stored in a parallel dimension and accessible on demand.

Maggie did not require a boost, but she attempted it anyway. This was standard operating procedure for bird lessons, during which her teacher could not speak to her. They were doing Follow the Leader — the golden eagle did something, then the magpie tried to do it.

Which means I shall be required to have fun first, the General thought. It was hard to show determination in her expression, but she flew straight and sure.

Unfortunately, Magnificent wasn’t fond of hunting and killing. That might not have been her fault. She wasn’t built for it — not like a raptor, at any rate.

Or there might have been something in the nature of Maggie that preferred thievery and cleverness over hunting and killing and that was why she had turned into a magpie in the first place.

Or it could’ve been that damn nickname.

Because of the war, the first time she ultimately had to confront the fact that her daughter was another person with her own needs and not just a complicated houseplant was when the Captain had dropped them both on that stupid island.

Magnificent was used to that stupid island. She had spent around five years alternating between the stupid island and the stupid boat and she was accustomed to stupidity. Not stupid herself, no, just used to coping with it and manipulating it to her own benefit. With no discipline, because what point was there to discipline when you could have whatever you wanted with a little cleverness and zero effort on your own part?

She hadn’t gotten bored with the lack of stimulation like her father yet — it probably helped that she had the boat and occasional encounters with the war — but she was still little. Her father had been six years older when he got frustrated enough to drag a pushcart onto the peaked thatch roof of his house.

The General was not used to the stupid island. She had been used to the stupid military, which was an entirely different species of stupid that at least operated by written rules. It had been like falling into an alternate dimension where nobody understood that of course you were supposed to wear shoes on the beach even if you got sand in them. What did sand have to do with anything? Mere sand was no master of the human spirit!

The Marselline Consulate, where she optimistically registered her new address with the Pension Office, had a bar and a slate pub sign out front with happy hour specials on it. It was an obscenity.

She had sized up her unruly daughter and her ridiculous surroundings and decided to organize them. Stubbornness and intimidation worked well enough on the Marselline Consulate — at least she got them to stop using the pub sign and wear suit jackets to work — but at five years old, Maggie was already quite stubborn and intimidating herself.

The General had conceived, from a bottomless well of personal stupidity that never seemed to run dry, that once she had battled her daughter’s will to a standstill, Magnificent D’Iver would be broken like a wild horse and eager to be moulded into the most formidable D’Iver woman Marsellia’s enemies had ever seen.

The golden eagle closed its eyes in pained humiliation. Maggie, I am going to have to ask you to forgive me for never being as smart as I think I am. Over and over again.

Magnificent’s hair, which her grandparents had allowed to express itself naturally with minimal styling, had struck the General as a liability. Moreover, it was representative of everything wrong with island culture and what they had done to her daughter in her absence.

Glorious D’Iver gave Magnificent an ultimatum — cut it off now or let me neaten it. After a knock-down drag-out fight, during which the five-year-old came in hot and the thirty-three-year-old coolly maintained her position and waited for her opponent to exhaust herself, Magnificent chose neatening.

In subsequent hairstyling battles, during which Magnificent continued to fight and cry out, the General used that as a bludgeon — Stop struggling! This is what you asked me to do! If you want to have your hair this length, you must take care of it. If you would consent to wearing it short, you wouldn’t need to put up with this nonsense.

Little toad.

The golden eagle shook the memory away. Not now.

Maggie was stubborn. Despite the fact that her mother was using a fine-toothed comb on hair entirely unsuited for it, yanking out tangles by combing from the top down, breaking strands by brushing it dry, and causing her constant pain by pulling the braid too tight, she did not consent to wearing her hair short. She would scream and hit and hide in impossible places all over the island, even devising her own primitive booby traps, but she wouldn’t have her hair cut short.

It had been her grandmother and namesake, Ameenah Sadiq, who finally put a stop to the torment. The woman had been a head taller than the General, with her own reasonably short hair bundled in a multicoloured scarf that added a good twelve inches, and there had still been a tremor in her voice when she brought the matter up: Brigadier General D’Iver, I know you are my son’s wife, but he is not here to deal with you and I am not going to let you hurt my granddaughter any more.

Hurt her? How have I hurt her, you stupid woman?

And the bottom had fallen out of her world, maybe even worse than at Valvienne. She had comported herself with dignity at Valvienne. On San Matteo, she had made a damn fool of herself ripping out her daughter’s poor hair until a third party intervened and told her to stop.

She had kept hold of enough of the training her own mother had drilled into her to say humbly, Please show me what I am doing wrong, Madame Sadiq. And, after it turned out to be damn near everything, Thank you, and, I’m sorry, Magnificent. I should have listened to you.

That was the first time she apologized for the hair. Every once in a while she renewed it — so that Maggie would be sure to remember it, but also so she would be sure to remember it.

A fat lot of good that did, Brigadier General D’Iver, she thought. Why is it that when my daughter is doing her level best to tell me I’m doing something wrong, my first instinct is to punish her for it?

She supposed she knew why.

I mustn’t think of these things now. I’m supposed to be having fun.

It was easier as a bird. She swooped sideways and applied her momentum to a loop-de-loop as the magpie followed her.

But she’s not having fun, she’s not doing it to enjoy herself. She’s waiting for me to teach her something because she doesn’t know having fun is worth learning.

She knew what she needed to do, what she had planned, but she still had to wrestle her sense of dignity to the floor and pin it for the count of ten. This is neither pointless nor stupid, it is a lesson! If I can’t really have fun, I am at least going to pretend for my daughter’s sake! Acting isn’t hard. For gods’ sakes, Miss Rose can do it!

…But I know I am going to fail. Eventually, if not now.

And I accept that. Yes, I do.

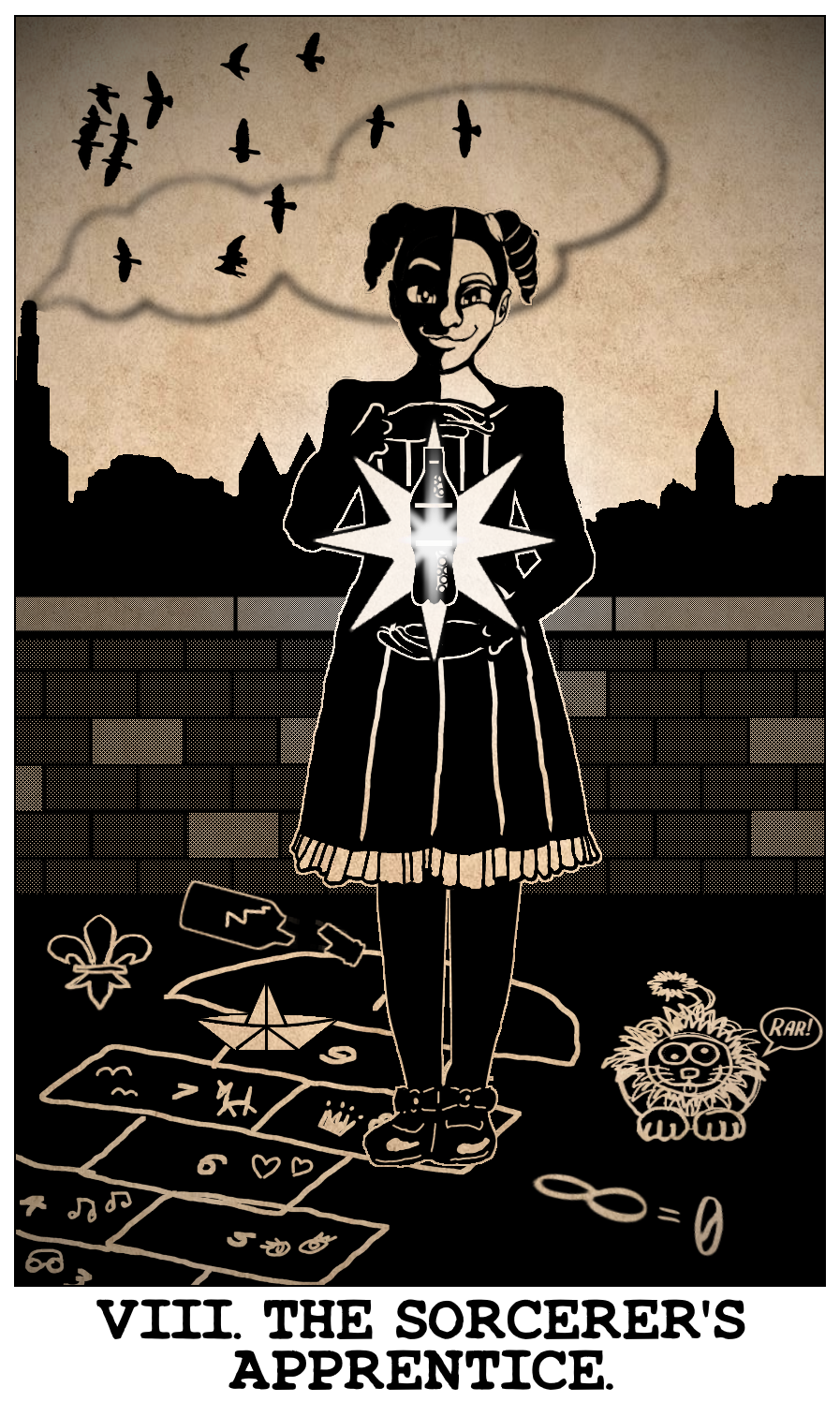

The golden eagle gave a cry. She tucked in her wings and executed several more loops through the nearest cloud bank, excising a good-sized chunk of the water vapour which she further defined with mathematics.

The refractory nature of water vapour lends itself to optical magic, Magnificent! This is essentially how I met your father!

She gave another cry, and the segment of cloud was shot through with a hundred threads of light, which were quite enough to turn it into a detailed double-decker bus with an ad for Rinswell Soap Flakes on the back of it — from all angles.

The magpie gave a confused squawk. It wasn’t a very difficult spell, not even for a bird, and she could see it. She flew around the bus once, then staked out her own section of cloud and, with another squawk, produced another, somewhat less-detailed bus. It was greyish and misty at the edges, the windows were flat white, and there was no ad on the back.

Apparently she wasn’t satisfied with it because she produced another bus, this one with sharper edges and a white poster with plain black printing that said: I FORGET WHAT A PIN-MIN AD LOOKS LIKE! on the back.

If the golden eagle could have groaned, she would have. I could have explained this when I had a tongue in my head, but nooo, I thought I could get it across! What a smart mother you have, Maggie!

The golden eagle did a barrel roll through another cloud bank, producing fluffy rainbow-coloured letters in her wake like a cartoon contrail: DO SOMETHING FUN! …followed by several purple stars and a flower like Magnificent had painted on the wall back at the house.

The magpie did her best to hover and observe this at a distance, then she flew past closely and went around the back like she had the bus: !OD GNIHTEMOS NUF

The magpie produced a flat yellow smiley face with its red tongue sticking out and its eyes pointing in opposite directions followed by a vague white question mark.

The question mark stung, but it hurt less than WHY? written across the sky in ten-foot-tall letters would have. The General supposed that would’ve been her reaction at Maggie’s age, if she hadn’t been too afraid of the novel situation. I’m the teacher, she’s just making sure, she told herself. She dove and produced a glowing green exclamation point that blinked off and on like a bar sign in fey lights.

Fear of novel situations was a product of what she had dubbed “collateral education,” and something she had put much effort into training out of herself. It appeared she had sidestepped that pitfall with Magnificent, if only narrowly. Maggie tended to slow down when she encountered a new thing she truly did not understand, but rarely did she engage in an unwarranted retreat or require rescuing.

…Maggie gave up and cried out for help most often in emotionally difficult situations, and in retrospect that should have been another red flag. She hoped her daughter was only missing information on that score and wouldn’t have too much to unlearn. Maybe she had internalized something like, “I can’t handle emotional stuff” at most. Not anything like, “I’m stupid,” “I’ll never be good enough,” or “my teacher will scream at me and drag me around by the hair if I get it wrong.”

She had put Maggie’s hair in a single tight braid at first because that was how her mother had braided her hair. Neatness was paramount, but it also made a convenient handle and an object lesson on why she would need to have it short when she began her military career. General Splendid D’Iver had not always pulled her hair to hurt, sometimes it was just a quick snap like a choke-chain on a dog, but young Glorious D’Iver knew it could be made to hurt, so she sharpened up quickly when her mother tugged her hair.

That was obviously a stupid and lazy way to train your child, and Glorious had resolved never to do it.

Hence, her horrified reaction when she found out she had been doing it anyway.

She did not want to teach her daughter to be afraid of her. There was a fine line between fear and respect and she treated it like a tightrope, one which she would rather die than fall off of. There was no net underneath, only a child who would see her as a weak, flawed human being and a hindrance instead of a help.

Quite by accident, she produced an image of a shaggy grey wolfhound with a duck in its mouth. She drew up short and then cut aside. If she could have blushed, she would have been.

I should have planned a limited menu of “fun” images. I am terrible at improvisation.

…That is not true. That is something she said when I was too slow or I came up with something she didn’t like or I objected to something she did. I am quite good at improvisation!

Just not in this specific case.

Magnificent did not appear to have assigned the dog any significance and she began decorating it with pink frosting and an Iliodarian hat.

“No dogs,” the General thought. When she saw that on the outside of Hyacinth’s house, she nodded and thought, Fine. That was before she got inside and noticed the hole in the roof. She had reordered her priorities at that point.

“Gentle When Stroked, Fierce When Provoked,” the General thought. That had been over the door to the kennels. It was a motto attached to the breed, nothing to do with the D’Ivers. If the D’Iver family had its origins in nobility (and they proudly did not), their motto would’ve included no gentleness, only explosions and screaming. Or perhaps, more subtly, a shield with two glaring eyes and a warning: Watch It.

The dogs were also a lesson. Several lessons. Painful lessons.

Wolfhounds are loyal to people, not territory. This makes them flighty and temperamental. You are not a dog, Glorious. Be better than a dog.

She did not object to being better than a dog as such, but her mother’s method of teaching had resulted in considerable collateral education.

“Collateral education” seemed more appropriate than “child abuse.” “Abuse” sounded petty, motivated by anger and without purpose. She was certain her mother had been trying to teach her the best way she knew how.

Most of the time.

She had been… Had she been Maggie’s age when her mother gave her that first litter of dogs? Older than eight, because that was when her mother had come home from the war to find a wild child adept at bamboozling her tutors and making up her own lesson plans. She might have been younger than Maggie’s age.

In her personal opinion that was too young to be saddled with troops. That was more of an age to explain: The dog has died. That means we can’t have it anymore. It doesn’t matter how much we loved it and how much it hurts. It is gone forever. That is not fair, but that is how it is. From this, we understand that life is fragile and has great value. It is not a toy.

Magnificent seemed to have picked up that lesson in part from Erik’s injury, fortunately. A real lesson derived from real life, and not a goddamned fake situation that taught fake things. Fake things like, “everything that goes wrong is your fault because you’re the one making the decisions.”

Stupid, stupid, useless and ultimately paralyzing lesson.

These are your dogs, Glorious. A litter of six. She had not said “men.” She had not said “troops.” It was implicit, but she allowed her daughter to put that together on her own, in hindsight. Then, after a few weeks, when a girl who was fond of animals had plenty of time to get attached, she had said, I am going to kill one of your dogs, Glorious. Choose.

With a few more decades of experience and confidence under her belt, she would’ve spat in her mother’s face. Then kill all of them. I don’t want friends that you’re going to kill. I reject what you’re trying to do, you bitch.

But she’d been too little. There had been a knock-down drag-out fight, during which she came in hot and her mother held her ground until she’d exhausted herself, and in the end she gave her mother Scarlet, because Scarlet had bitten her once and wasn’t as nice as the others. (She had already named all of them. She named them the first day.) Her mother broke Scarlet’s neck and took her away and then she had five dogs.

A few weeks later she gave her mother King, and then she had four dogs.

She hung onto Lucky until the bitter end, because Lucky had been little and sick, and needed hand feeding with a bottle and she loved him the most.

She knew damn well her mother had been after Lucky from the start — she had even known it at the time. If she’d agreed to cull the weakest member from the pack she might’ve had five dogs and no more fake lesson, but she was stubborn, and too little and dumb to realize the good guys don’t always win because they’re right.

She had pictured running off into the woods with her remaining dogs, and becoming some kind of legendary wolf-woman — protecting the weak and living by her wits, with a lot of puppies. But in the end, she let her mother winnow her first army down to one sick dog who loved her very much, and one day when she came down to the kennels to play with him, he was dead.

I am certain she poisoned him.

She took a sudden, screaming hundred-foot dive trying to shut up the thoughts in her head, but even the wind wouldn’t blow them out of her brain.

Of course she poisoned him. It was a fake lesson, false from beginning to end. If the dog wasn’t considerate enough to die on his own and hammer home the point, she had to kill him to prove herself. She was stupid that way.

Just before roof level, she redirected sharply upwards and cheated physics just enough to power herself above the clouds and look down at her wide-ranging attempt at “fun.” Three double-decker buses, rainbow letters, stars, flowers, a goofy smiling face, a dog in a hat, a strawberry shortcake, a sailboat, a storybook moon with a sleepy eye and a nightcap, a giant squid, an ice cream sundae, a milkshake, and a ladies’ hat with an entire stuffed albatross perched on it.

Her eyes were damp. It was the wind. Eagles didn’t cry.

What is the matter with me? I’m up here building ice cream sundaes out of clouds with my brilliant daughter on a beautiful sunny afternoon! Why am I thinking about a bunch of dead dogs? Why can’t I have fun?

…Because it’s a high-stakes novel situation and I can’t accept that I’m going to fail. So I’m filing through everything else I’ve messed up looking for mistakes I don’t want to repeat.

Because I don’t want to ruin my daughter and I don’t even know if this is the way to help her.

And I don’t know if I can.

A load of collateral education and a lack of fun didn’t ruin me, now, did it? she thought, distantly observing as Maggie put the finishing touches on a frog with a banjo.

No, she wasn’t ruined. She was quite proud of herself most of the time. Smug, almost. But she was also relentlessly self-critical, insecure, anxious, near useless at teaching emotional regulation, and no damn fun.

Observable reality suggests I am extremely fun and perhaps even a bit madcap, she scolded herself. This is rather spectacular for a first try, Glorious.

Ah, but never good enough, she thought, winging downwards with the intent of adding a lily pad to Magnificent’s frog. Always trying to correct myself first, before somebody yanks on my hair or another dog dies…

She had adapted. She had lost a few more dogs, but never a whole litter again, and many more men. She knew she would never be good enough, so she compensated for her shortcomings as best she could — including her tendency to overanalyze. She attacked life like an enemy regiment; life seemed adversarial enough to deserve it. Defeat was a much better teacher than victory, if not any kinder than Splendid D’Iver. She had done her best to weaponize her certainty that she was bound to fail, to turn that constant, nagging insecurity on its head.

You are going to fail, she would tell Maggie, much like her mother had told her, and as she could not stop telling herself. If not this time, then another. And it is going to hurt.

But she didn’t leave it there. She was better than a dog, and also better than her mother.

We are smart people, Magnificent. We don’t throw away a perfectly good lesson just because it hurts or we don’t like it. We figure out how to use it, even if we find out we’ve been using it wrong. We improve.

Failure, Magnificent, is only the beginning.

Today, Brigadier General Glorious D’Iver has failed to have fun. So she will learn. And tomorrow she will try again.

◈◈◈

Mordecai had departed the kitchen to hang a damp dishtowel over the back stairs. He returned still clutching the dishtowel, and he trod in the wash bucket where Hyacinth was scrubbing a jelly-glass.

“Hey!” she said. “Get your damn dirty shoe out of my dishes!”

“Hyacinth,” he said, shoe in her dishes. “I have… I have heard things about drug-fuelled flashbacks. But I do not have any personal experiences to compare and I lead a strange life. For instance, Lucy’s highchair looks like an enormous pink spider and several outside parties have confirmed this… So I wonder if you might come outside and, ah, take a moment to confirm the sky?”

Hyacinth accompanied him outside, dripping, and had a look at the sky. “‘Do something fun,’” she read aloud.

Mordecai nodded enthusiastically. “Ah! Yes. Yes, that will do, Hyacinth. Thank you very much. There are three double-decker buses up there, aren’t there?”

“That I notice,” said Hyacinth. “…And we’ve just added a snowman!”

Erik joined them on the back stairs and looked up. “It’s a lesson,” he said. “The General thinks Maggie doesn’t know how to have fun. She doesn’t know Maggie wasn’t having any fun because she thought her mom didn’t love her anymore. But I think this fixes it anyway.”

“They’re painting the sky!” Calliope cried, observing from the kitchen window. “I’m going up on the roof so I can see all of it! Come on, Lu!” She tapped the Lu-ambulator and asked it to follow her before running out.

“We might as well,” Hyacinth said.

“I’ll get a… blanket!” Erik said.

With Lucy beside them in her crouching spider highchair, they lay on the peaked roof and identified the clouds for a good hour. Meanwhile, in the city, many others took DO SOMETHING FUN! as a divine edict and did their best, in terror for their lives, while the police and the government tried to figure out if celestial vandalism required investigation or an arrest.