Maggie was awake. So she knew, on a base level, that her mother was also awake. It didn’t even startle her when a voice spoke up from the larger bed above her, “There are pigeons in the house, Magnificent.”

The brown girl in the thin white nightdress sighed and threw down her blankets. She sat up with limp arms in her lap and a long-suffering expression.

There were, of course, no pigeons in the house. This was a joke, on par with the endless bags of barbecue potato chips that her mother pulled out when she wanted to murder some seagulls. Brigadier General Glorious D’Iver thought an excuse for some senseless violence was the funniest thing in the world. Her daughter Magnificent just thought it was boring as hell.

“There are pigeons in the house” was code for, “Some foolish people have broken into the house, and we are going to use them like pigeons.” But that no longer needed saying. Hadn’t for years.

There was a sound of clinking glass in the kitchen which stood out to both D’Ivers in the still of the night like the rattle of a telegraph key: We’ve come in the back door and we’re in the kitchen, STOP. We suspect nothing, STOP. You might as well eat us, it’s not like you can call the police, STOP.

“Are you sure it’s not Milo eating cake?” Maggie said, without much hope.

“That is a wilful lack of deduction, Magnificent,” the General said. “The cake is in the basement, with the rest of the leftovers. Mr. Rose is aware of its location, and the location of all the necessary utensils in the kitchen. He would quietly select some and depart. The noises continue.”

“Yeah,” Maggie allowed.

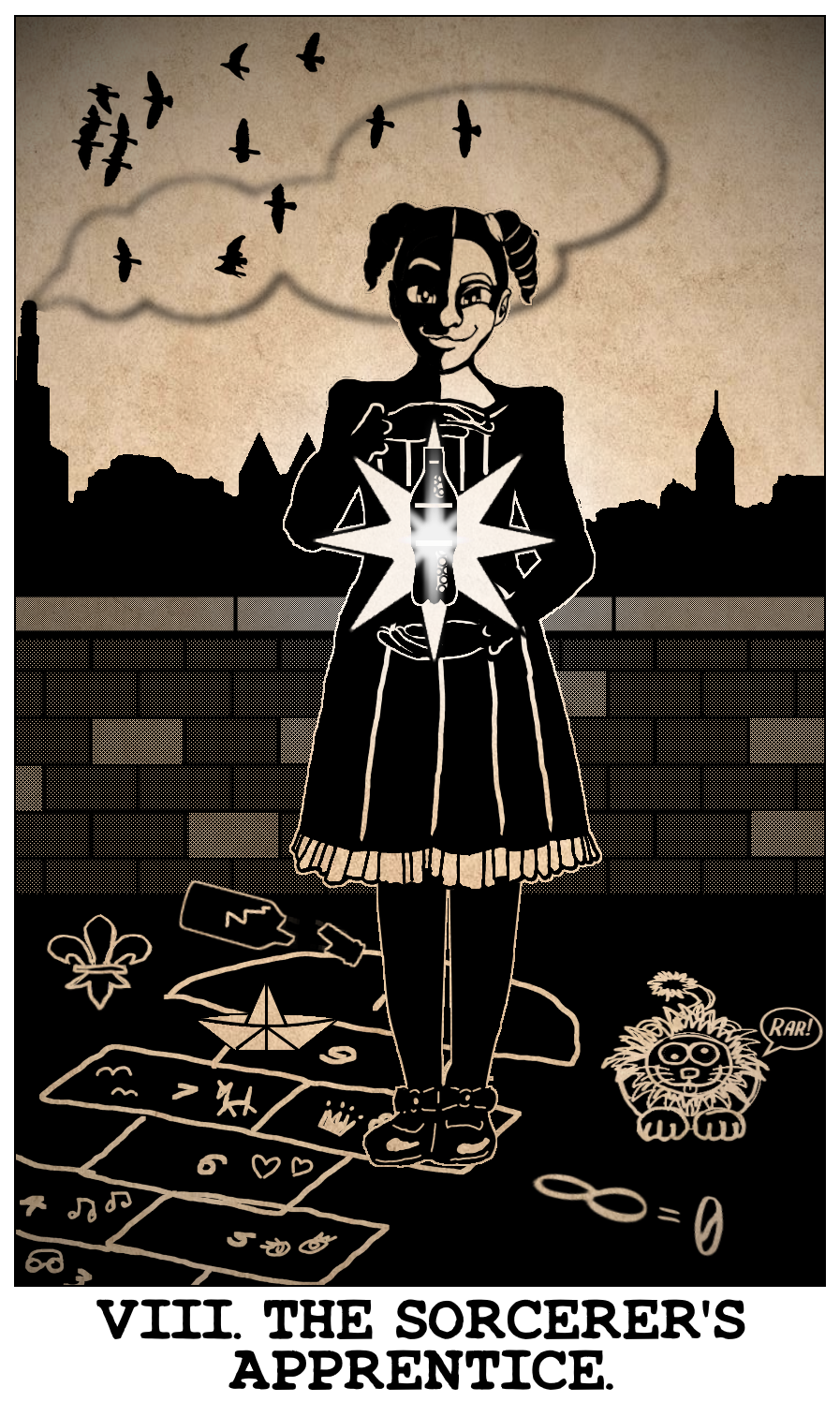

The General leaned on a casual elbow and offered an educational incentive with a smile, “What if we practice your fireballs?”

“Not inside, Ma,” Maggie said.

“‘Mom,’ ‘Mother’ or ‘Sir,’ Magnificent,” the General said tightly. “A sheep says ‘Ma.’” She slid out of the bed and stood. Her nightgown was but slightly wrinkled and her dark hair too short to be even a little dishevelled, battle-ready at three o’clock in the morning. She looked like a sculpture in white lard, glistening in the moonlight. “I will intervene to prevent you from damaging the house, if necessary. It will not be, if you remember to mind your control.”

Maggie sighed again. “Oh, all right.”

◈◈◈

Maggie tiptoed down the cold tile stairs in her bare feet. The General went over the banister and descended like a horror movie special effect, the lower hem of her nightgown flapping softly around her ankles. She mouthed words at her daughter when they met up at the bottom of the sweeping staircase: How many?

Maggie held up her index finger, frowning. She felt kinda sorry for the guy. He was going to get set on fire about a dozen different ways before they let him go.

The General nodded.

The lights were on in the kitchen; they were automatic. This had apparently not dissuaded the idiot in the kitchen from collecting Hyacinth’s money jar, and then searching for whatever other items of value might be in a magicians’ pantry.

Maggie and the General split up to cover both doorways — Maggie cut through the dining room, which still had the table and chairs set up from dinner, and the General edged past the darkened tree in the front room.

In the kitchen, a blonde woman in stained canvas trousers and a worn blue blazer was standing at the counter and eating a leftover crescent roll with butter from the ceramic crock. The ragged tin knife was on the counter surrounded by crumbs. She turned and smiled bashfully with crooked teeth, revealing one arm in a sling. “Oh, hey, you guys. Sorry. I’ll get out of your hair…”

“Corporal Santee,” the General said.

“Sir!” She saluted with her crescent roll.

A dollop of oyster stuffing fell from the ceiling.

Maggie extinguished her fireball.

◈◈◈

The General’s “office” was just down the “street” from Comms. The office, as well as Comms and every other room in the place, was a hole with sandbag walls and a dirt ceiling held up with planks and magic. The street was a trench, albeit a nice one about three miles from the front. Just enough of a buffer to get some real work done, like relaying orders, plotting tactics and minding the wounded.

The “hospital” was a few doors down. A slope had been dug out next to it for the ambulance — which would be driven at high speeds by true heroes to evacuate the badly injured to greener pastures with less bombing and shooting.

It was eerily quiet for daylight hours. Only the distant sound of abandoned ordnance in No Man’s Land detonating in the heat reminded one that there was still a war on. Technically.

A fat black cable wound its way in through the doorway like a python. It powered some rudimentary lighting, a balky electric fan, a radio and a telegraph. The radio was tuned to a nearby station, blaring a soap opera in Alemanian. No newsflashes yet. It was imperative that she beat the newsflashes. A lot of the soldiers carried radios too.

She could hear a few of them singing the Third Coalition Anthem, such as it was. “…We all stand together!” They broke off in laughter. They were suspicious, but in a good-humoured way.

She had to be so very careful with this. This was her last battle, at least for a time, and she was fighting for the wellbeing of the men and women beneath her. They mustn’t do anything rash.

She mustn’t do anything rash.

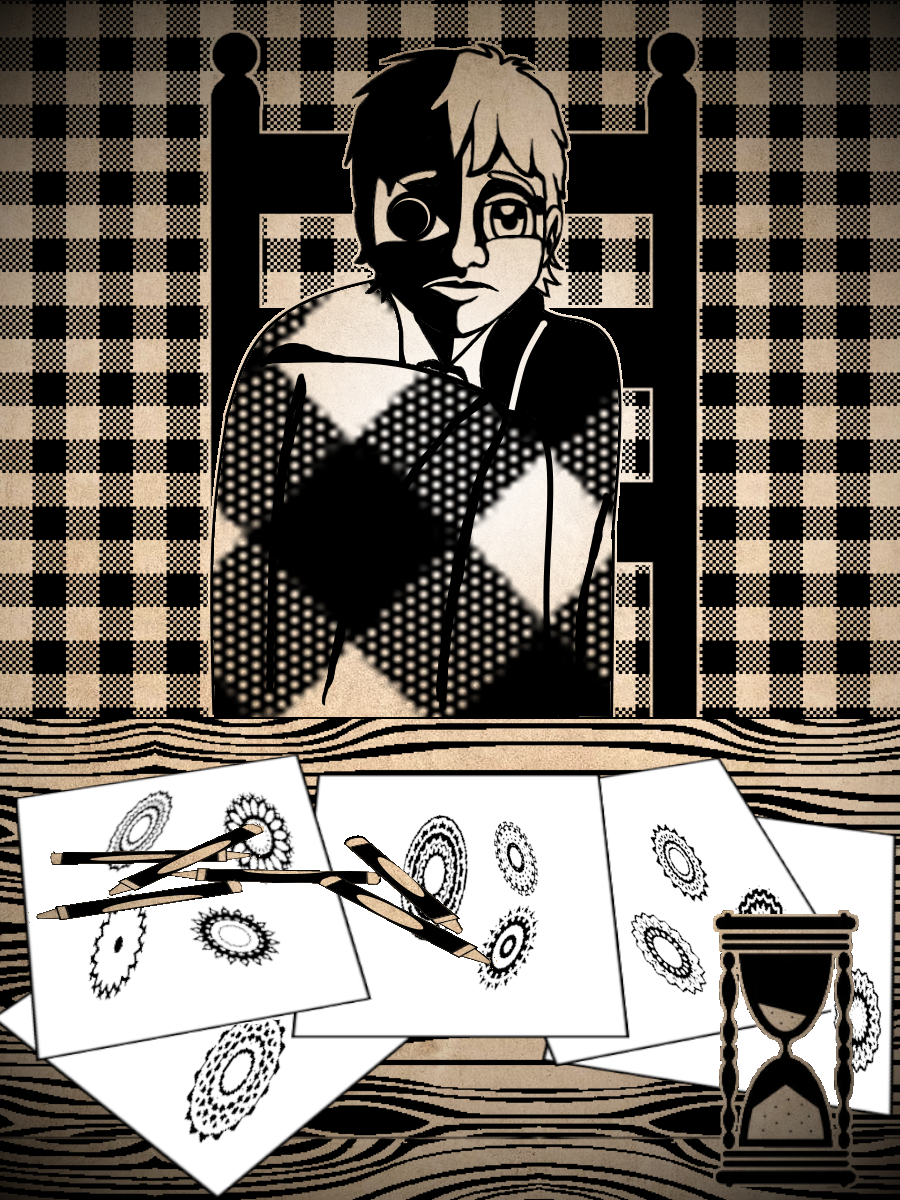

She snapped the pencil in her hand. These damn pencils seemed ridiculously fragile. She pulled out a drawer and deposited the remains in the graveyard with the others. A fresh, pre-sharpened pencil came out of the box on the desk blotter. She paused and erased, then continued to write.

Ink was for crossword puzzles and other frivolities. Tactics and matters of life and death required the ability to erase — that was a luxury she had in her office, when she spoke words they became etched in stone.

Nevertheless, she intended to take the time to produce a clean copy of this. One for the history books, where hopefully she would not be held up as a laughingstock and a model of incompetence.

The Marselline Surrender at the end of the Great Undertaking, or whatever we’re going to call it now that we’ve lost, 1359-1371, was irrevocably bollocksed up by Brigadier General Glorious D’Iver at Valvienne on July 19th. There were riots and many men died. Her mother (General Splendid D’Iver, 1303-1367) would have been dreadfully disappointed.

She snapped another pencil and snarled at it.

(They didn’t put that part in the history books, with the speech — of which she did at last produce a clean copy, for posterity. The part with the broken pencils and the emotional war in her own head. History tended to produce its own clean copies, if the moment was sufficiently iconic.)

A man wearing a white coat and a grey helmet with a single artificial tree branch sticking out of it knocked on the wooden support of her door frame. Such helmets were kept in haphazard piles around doorways for walking down the “street” in relative safety. He hadn’t even bothered to fasten it. “General D’Iver? It says ‘Do Not Disturb…’” In glowing yellow letters that flashed on and off like a fey light. She had applied them herself.

She straightened and stood. “You are allowed, Dr. Rostami. I asked you to disturb me. How is she?”

He bowed to her and automatically removed the helmet. He might just as well have written “I am only a volunteer” in the air as she had done “Do Not Disturb.”

“She is adjusting.” he said. “The fever is down. It seems her body will accept the mergers…” He shook his head. “But she is still unconscious. I’m sorry.”

“It is about what I expected, Dr. Rostami,” the General said stiffly. “I am more than convinced of your competence. There are circumstances beyond your control.” She allowed herself a sigh and turned back towards the desk. “It is a shame. She was a good witch.”

“She may pull through, sir!” the doctor said, fumbling his borrowed helmet.

“She may,” said the General. “But there will be no more witches.”

“Is it true, then?” he said, behind her. “Is it another coalition? Are we pulling out?”

She drew herself up. “I will be going forward to make a speech. You may listen at Comms.” She put a hand on his shoulder and spoke more gently, “We have time. In any case, we have time. There is no danger to the wounded.”

He nodded, replacing his helmet with new urgency and a nervous lack of coordination.

She did up the strap for him. “Buckle your safety belt, Dr. Rostami. I am a Brigadier General and I have more to worry about than your head.”

“I apologize, General D’Iver.”

She waved him off. In her mind she was already erasing lines and scratching new ones.

An urgent voice broke into the droning radio, utterly derailing her train of thought, but it was only the score of a football match. She knew enough of the language to tell that.

It was a shame. That was true. It was a crying shame. Corporal Corinne Santee was a damn good witch!

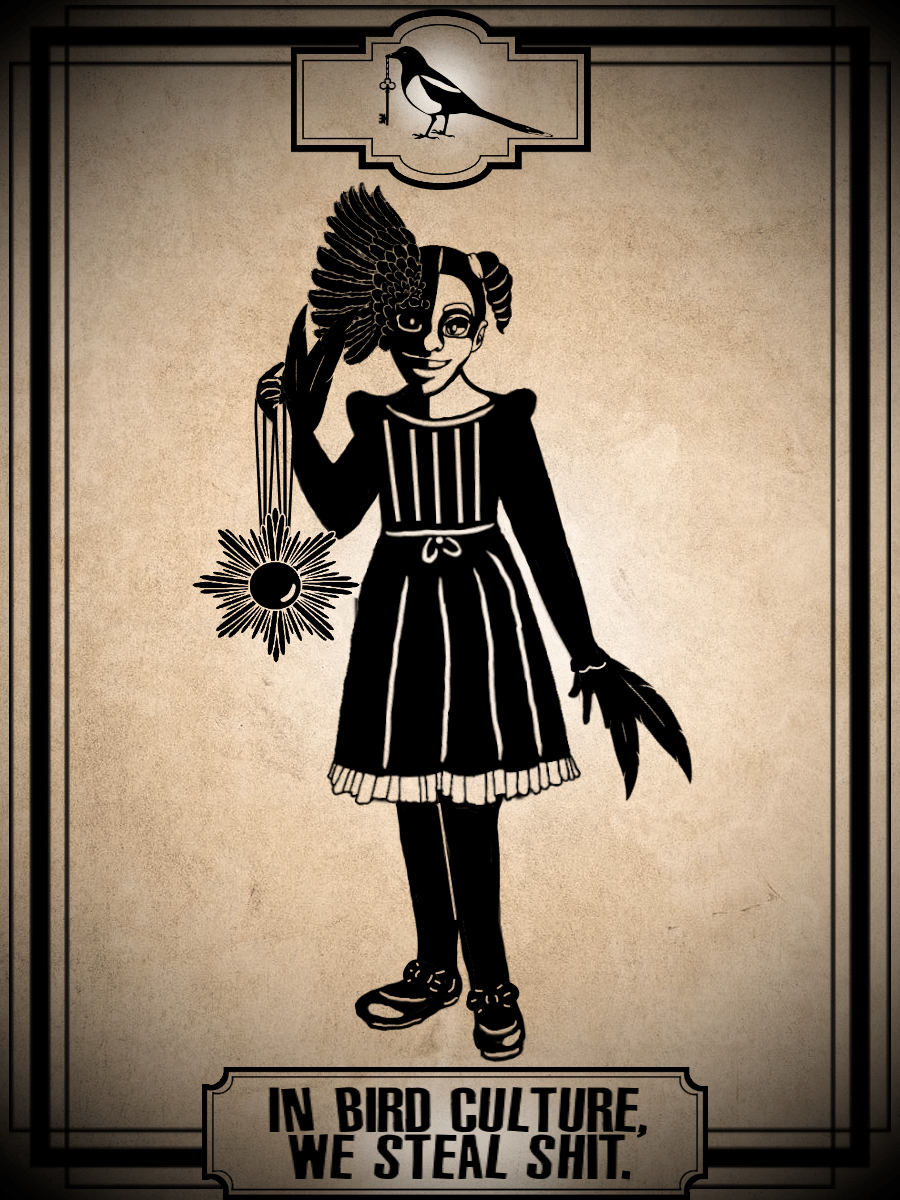

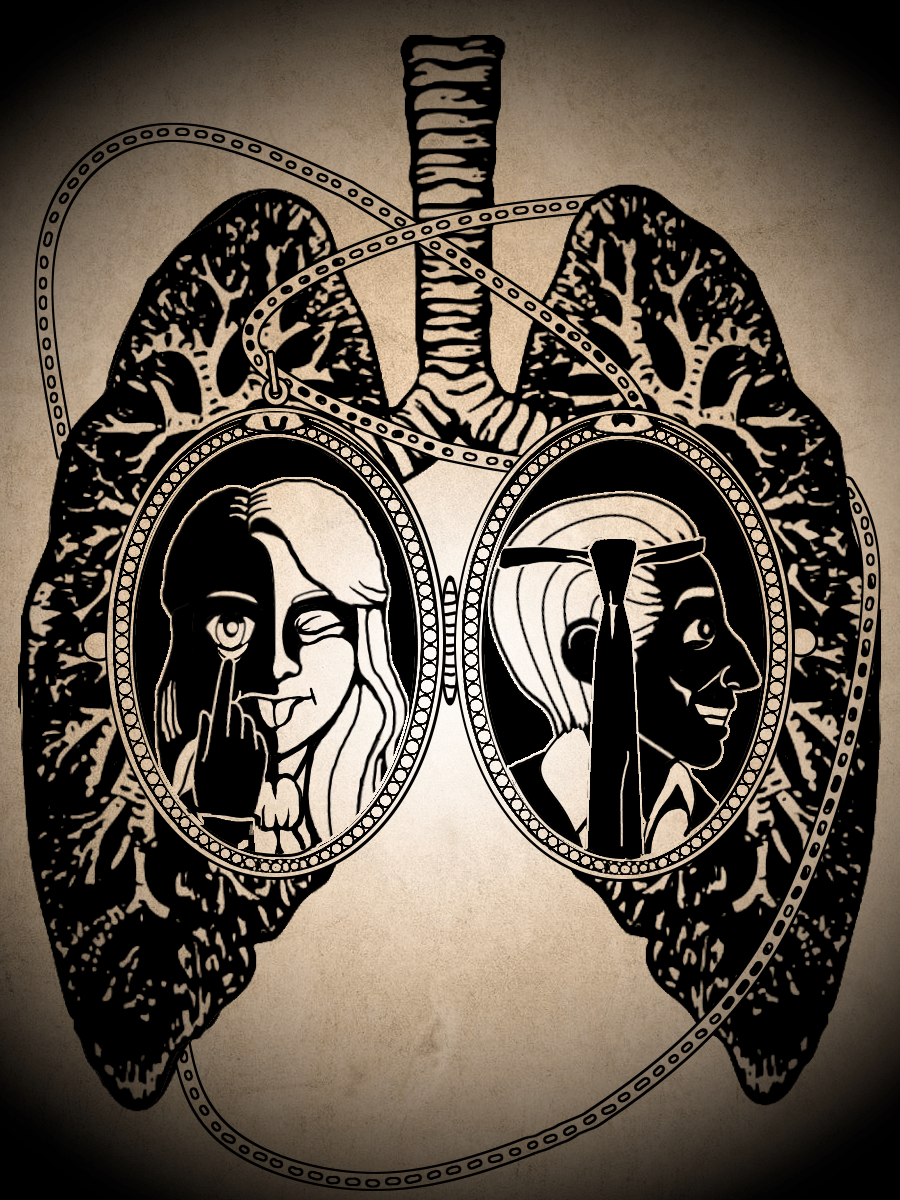

The need for witches was idiosyncratic and specific only to women of her family — the others of whom were either deceased or too young to be turning into birds and going to war, so at this point just her.

It was very hard to do magic as a bird, lacking hands for complex gestures and a voice for trigger phrases. Everything had to be constructed from scratch, and even that was more difficult. The diminished alma in a bird body might have had something to do with it, she was researching that in her spare time.

With limited access to magic, her bird form was comparatively fragile. She was also rather conspicuous; people aimed at her. In fact, entirely new forms of magic had been developed to take General Glorious D’Iver and her kin out of the sky.

Embarrassing as it was, she required protection. Whenever possible, she flew with a guard of four people — one behind and below, one on each side and one in front. Ideally they would be women with small, light bodies, and on the smallest, most manoeuvrable aircraft available: broomsticks. Hence, witches.

Soldiers had excellent, if obvious, senses of humour.

Corporal Santee was a damn good witch, both a maverick and a virtuoso with a broom, and when she was along, she always rode point. The front position required the greatest measure of alertness and control. It was also the most exposed.

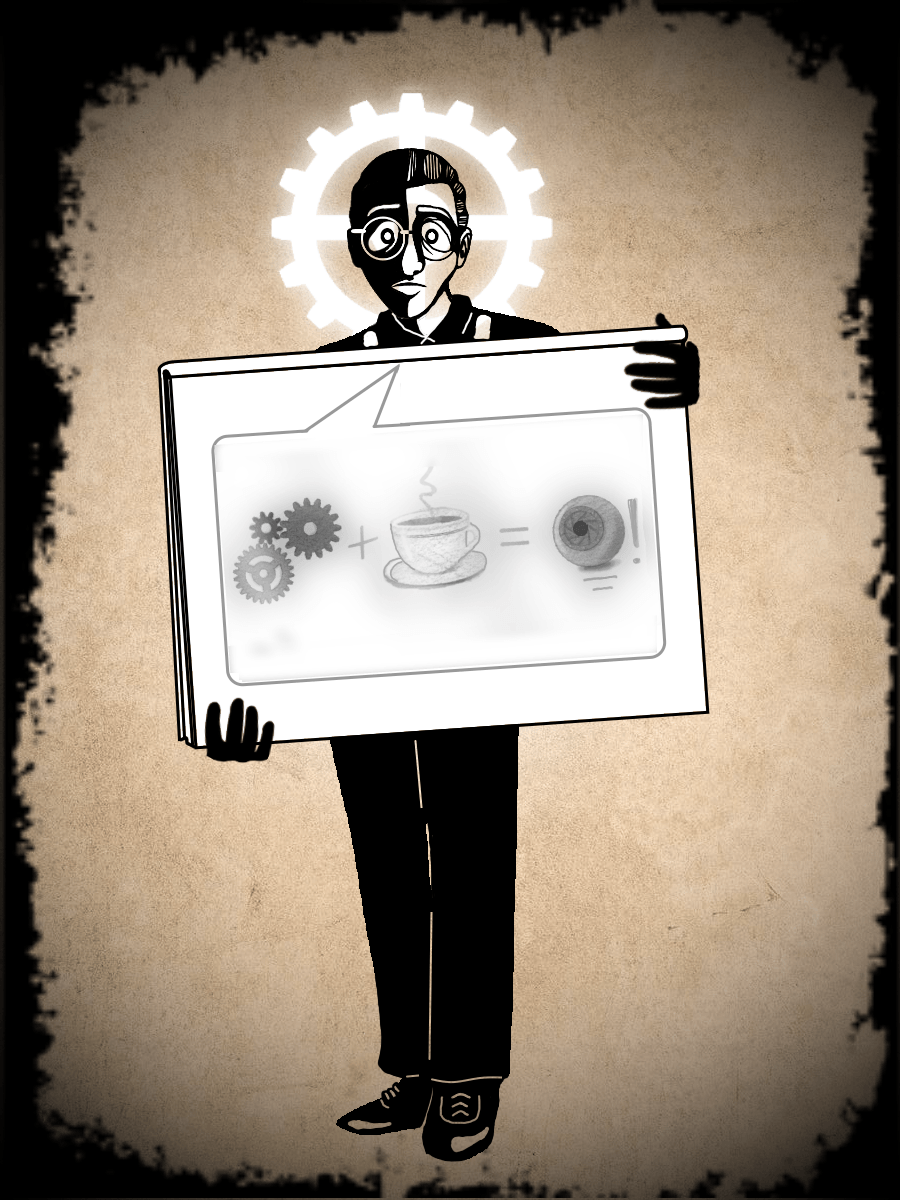

Buzz bombs were one of those new types of magic that had been developed to mess with ladies who could turn into birds and lately flyers of all kinds. Small clockwork devices with insectile manoeuvrability, they found purchase on some solid object, even each other, and performed a central deconstruction. An explosion which required no gunpowder and produced its own shrapnel resulted — usually of flesh and bone.

Despite the ease of shield spells to human hands, she had lost several good witches in that way. Shield spells curved visibility like a fisheye lens, and buzz bombs were just so tiny. If you threw up a hand and caught three of them, you might miss a fourth and fifth because of the blast and the distortion. It was not possible to see everything, even with five sets of eyes. If not a buzz bomb then a bullet or a nocker or a shell.

She might not have died. She could do shield spells, just not as quickly as her coven of witches. She might have seen it and caught it herself.

But Corporal Santee didn’t give her the chance. She flew in upside down with no hand on the stick — her left already holding off a nocker the size of a football, as her right came up and caught, literally caught, the round metal buzz bomb that might not have killed the General.

General D’Iver saw with eagle’s eyes what might’ve been a manic grin, or just a grimace, before she got her shield up to protect the rest of her witches from the blast.

Corinne fell, not quite whole. The deconstruction had centred on her palm rather than her torso, but it had been enough to take off her arm above the elbow. By the time they returned and found her, one of the medics had already tended her and overwritten the wound with stone. Private Forsberg brought her back to the hospital tandem on her broom, at great personal risk, and Dr. Rostami patched her up the rest of the way.

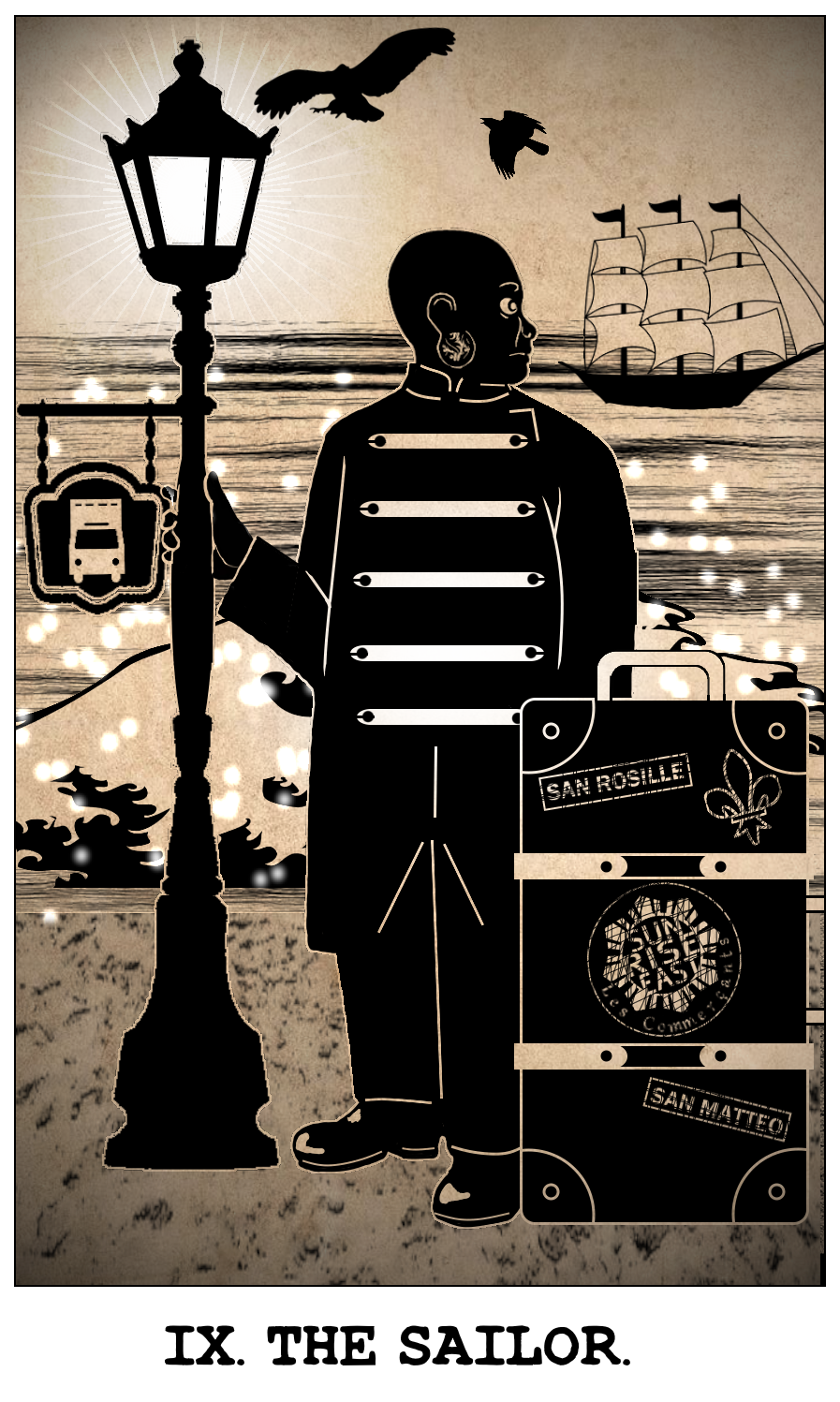

She had remained unconscious for three days now. If she could be expected to survive the trip, she would be loaded onto an ambulance and evacuated to Piastana, neutral territory. Any recuperation would take place there, before she was shipped back home to San Rosille — still the capital of Marsellia, as the General recalled the treaty, just under new management.

This time she broke only the point of the pencil. She threw it in the drawer with the others. She didn’t have time for sharpening.

It was a waste. A waste of pencils and a waste of lives and a waste of people. It wasn’t even a real defeat. They weren’t being driven out. Some men a thousand miles away signed a piece of paper and now they were abandoning a strategically valuable position where they had been gaining territory!

Furthermore, they were abandoning their sovereignty as a country — as an Empire! — and she had to find some way to explain and justify this decision that she had been in no way involved in and would never have made herself.

It was a waste of hope. Both the aggregate variety which she had come to rely upon to move mountains, and the individual sort which led people like Dr. Rostami (and even the incompetent Mr. Dreyfuss) to volunteer and follow them to strange countries and get shot at, because they sincerely believed that they could help others and make a difference.

I will need to make a remittance of their hope, she thought. I have none of my own to spare, but we shall see how much credit they are willing to give me.

Half an hour later, still ahead of the scheduled surrender and the newsflashes, she approached Comms in full dress, including feathered hat, with her clean copy and her pencilled notes in hand. “I am going forward. Are they ready for me?”

Comms already knew, and doubtless the radio operators at the front suspected — though they might have assumed a new coalition or even a victory instead of what she was about to announce.

The atmosphere was bad. They were pale and subdued. “Nearly, sir,” a young man said. “They’re able to broadcast. They can’t find a mic stand, you’re going to need a mic stand.”

She did not require a mic stand. Nevertheless, she accepted the case with the folded object inside. “Thank you.”

A young woman listening to a radio with a headset covered the microphone and burst into tears.

The General approached and put a hand on her back. “It’s not the end, Private Sieger. Pain is required of us, but not the end of us. We must carry on. We owe it to the others, and to ourselves.”

She sobbed and nodded. “Yes, sir.”

The General raised her voice and addressed the room at large, “It has been my honour to serve with all of you. As always, I must ask you to push a little harder and give a little more. Know that you have my gratitude, and my respect.”

Soft voices answered, “Sir.” “Sir.” “Sir.”

She nodded to them.

With the preliminary ceasefire still holding, she flew off alone. The sky was clear and faded denim blue. The sun beat down on her back like a drum. The churned and muddy fields below, pristine with waving yellow grass only a season ago, looked wounded.

She landed well clear of the trench, so that the flash and noise of her transformation wouldn’t set off any nervous triggers, and announced herself before climbing down.

There were two very nervous radio operators, a man and a woman, who were apparently tasked with getting the contents of her speech out to the area. She handed them the mic stand in its case. “Where do you want me?”

Ashamed, they led her to some piled up crates with wiring snaking around them and a single microphone resting on the splintered planks. A few soldiers had gathered around, but they were all on one level, helmeted with heads not even cresting the lip of the trench. Even with the crates, neither would hers.

“No,” she said. “I know this is short notice, but I need them to see me… As many of them as possible.”

The woman was setting up the mic stand without much hope. The man shook his head. “I’m sorry, General D’Iver. It would probably be better from Comms…”

“No, Lieutenant, not in this case.”

“Sir!”

“How far will these wires stretch?”

“There’s about ten feet of play in ‘em, sir,” the woman said.

“That will do. Thank you, Sergeant.” She stepped onto the boxes. The woman moved urgently to shorten the mic stand for her. “No, I can do that myself.”

Brigadier General Glorious D’Iver took hold of the microphone, and stand, and ascended vertically — ten feet straight up — to the sound of muted applause and cheering from the tired soldiers around her. She anchored the microphone at an appropriate height and spoke into it, “Are we broadcasting?”

They left that part out of the history books too. And the fact that her two unfortunate radio operators crashed into each other trying to ascertain whether they were, and at enough volume. While she waited for them to straighten themselves out, a young private standing several feet below called up at her: “General D’Iver! Who are we allied with now?”

She covered the microphone and leaned down to address him, “I regret to inform you that we appear to have allied ourselves with Prokovia.”

They didn’t put that part in the history books either. Nor anything about the unfortunate young man, who paled and sat down in the mud.

She wanted to apologize, she shouldn’t have put it that way, but then her radio operators gave her a thumbs up and it was time to apologize to all of them.

“Can you hear me?” she inquired of the microphone.

There was some applause and some cheering. A few heads popped up out of trenches nearby, like mole people. They trusted her, perhaps too much. Some of them hadn’t even bothered with helmets. They knew she wouldn’t make an obvious target of herself like this if there were any danger.

“It is my duty to address you this afternoon,” she said. “Doubtless, most of you already suspect that something has happened. We are currently operating under a provisional ceasefire…”

There were more cheers and applause. She spoke over them, raising her voice, “But errors are likely at times like these, so I would appreciate your continued caution.”

A few mole people disappeared and reappeared with helmets.

She waited for quiet before beginning again, “At four o’clock this afternoon, we will conditionally surrender to the nation of Prokovia. A treaty has already been signed. The terms are provisional, but Marsellia’s surrender itself is not. The war is over. We have lost. We are going home.

“Please!” she said, over the resulting dismay. “I have been informed that what we have achieved in this manner is ‘Peace with Dignity,’ and that our lives will continue much as they always have.” She lowered her voice, perhaps an octave, and her head as well, as if she were readying a charge. “I find this highly unlikely.

“We fight for change!” she declared. This was usually where the schoolchildren who chose to recite it for a history lesson picked it up. That first part where she had to explain three different times that they had surrendered, for the benefit of radio static and incredulous minds, was bad for morale.

“We fight for the betterment of all! Not only for ourselves and our homelands, but our children, and their children yet unborn. We climb mountains knowing we may die on the slopes, never seeing the summit, but knowing, too, that those who come after us may use our bodies as purchase to reach heights undreamt of!

“We fight for change! Though change be fickle and violent, and liable to cast us into valleys of despair as we reach for the stars! We will return from battle to find our homes changed, our people changed, ourselves changed. Much of what is lost can never be regained, and our hearts ache for friends and family and familiar places, for innocence.

“This is the price we pay for a chance, for merely a chance, to grow beyond what we already are. To achieve great things we risk all, and lose much, every time. And sometimes it seems we lose everything. As we sit among the ashes we question our devotion to change, the audacity of desire, our self-worth, our sacrifice, and the sacrifices of others.

“But we must be brave. We must look to the future, though it seem bleak and intolerable. The battle is not over, it has merely changed.

“Swords may be beaten — beaten, I say! — into plowshares, but the mettle of a man remains as strong. So, too, after turning its nose to the dust for a time, a plowshare may be reforged into a sword!

“In obedience to our negotiated ‘peace,’” the quote marks were implied, “I must send you into this next phase alone, without weapons or support, without the daily issue of commands to which you have become accustomed. Thus, I bid you to heed me now, and remember: I must once again ask you all to push a little harder, and give a little more. I ask you to pick yourselves up again, even if I cannot be there to catch you when you fall.

“You must rebuild. Take up new weapons, those which are appropriate to the venue. Your dedication will serve you well, whether to education or employment, or family life. Construct new regiments and systems of support — do not neglect to include civilians, even mothers and children may serve in this capacity. Marshall your faith, your hope, and your trust. Seek aid when you require it, without shame, for these are strange and difficult times. Above all else, do not give up! Push forward, dig in, and survive!

“I would remind you, we have had many ‘peaces’ such as this, and they are apt to end quite suddenly. ‘Dignity’ is no balm to a brave heart that yearns to beat freely. Today, I have only ashes for you. It is your duty to accept them, no matter how cold and bitter. It is your duty as it is mine. But this is not the end! It is our nature to rise again in flames! That can only be delayed, it cannot be denied! The day will come when I require your steel again — keep it strong!”

“We’re with you!” cried the female radio operator beneath her. She gasped and covered her mouth with both hands. The mic didn’t pick it up, but the people around her did. They cheered, and the cheering spread outward from there, leaping from trench to trench where soldiers stood on boxes, or climbed ladders, or even sat on each other’s shoulders to see. It was a roar, nearly a snarl, the sound of raw determination.

“This is not the end!” a voice cried from a distant trench. They began to chant, “This is not the end! This is not the end!” A beat like the baking summer sun. The mic picked it up and carried it to distant places, even more when the speech was rebroadcast, minus the sight of red faces with open mouths and fisted hands.

“My soldiers,” the General continued after a pause. “My people. I do not dismiss you. In the truest sense, I never shall. You will receive new orders within the hour.” This part was truncated from the subsequent broadcasts, the part about the orders was increasingly inaccurate and it was easier to cut off the speech after the cheering, but it remained in the history books.

She descended amidst shouts and applause.

The male radio operator removed a truly ridiculous set of outsized headphones and dropped them in the mud. “Sir!” he said. “General D’Iver… Let’s keep going!”

“I’m sorry?” she replied.

He cast his eyes sheepishly aside and waved a vague gesture. In the distance, people were still chanting This is not the end! “Let’s… Let’s just… keep going,” he said. He lifted his eyes but not his head. She was quite a bit shorter than him. “We can do this! We’ll fight the Emperor if he won’t come with us!”

The woman beside him slipped her headphones down to her neck and nodded gravely.

The General had been wary of this sort of thing. She had also wondered, if only for a moment… But this was a matter of loyalty, not of possibility.

“Not today, Lieutenant. Sergeant.” She nodded to them both. “Today I can only give you what has been given to me. It may not be to your liking, but good steel must be tempered. This is our duty. Rest your swords.”

“Sir!” They saluted her.

In the following days, her troops in Valvienne and the surrounding area calmly broke ranks and turned in their weapons without issue. Many, with vague hints of menace, demanded that the guns and blades be kept in good working order, others avowed that they didn’t care what happened to the old ones, but the new ones would need to be even better. There were no rash actions or unnecessary casualties, as there were on other battlefields where the commanding officers emphasized “Peace with Dignity.”

When she returned to Comms, they were all standing at attention for her and she had to direct them back to the radios. There was much detail and information that needed to be distributed, and reactions to manage. She asked how it was going so far.

“They are ready for the coming fight, sir!” Private Sieger informed her.

“Kevin is a bit worried you’re going to leave him behind, sir,” Corporal Kelly added with a smirk. “Because he’s not a soldier.”

“Oh, ‘Kevin,’” said the General. The quote marks were implied. She snorted and tossed her head. “Remind Mr. Dreyfuss that I am not in the habit of leaving any of my men behind and that he was assigned to us. If that fails to quiet him, I suggest you drape a rag over his cage so he thinks it is night.”

“Sir,” they replied, with stifled laughter.

Dr. Rostami was waiting for her in her office — also at attention, such as he was able with only rudimentary training.

“Doctor, I will inform you as to the details of the evacuation as soon as possible. I must ask you to be…”

“She woke up, sir!” he replied, beaming.

“Corporal Santee?” she said.

He nodded. “She asked after you. I let her know you were still alive, but you were busy at the moment.”

“May I…?” she said.

“No, not yet. She is tired.” He frowned and stepped forward, reaching out. “Her injury… Head injuries are unpredictable, General D’Iver. You may need to manage your expectations…”

She stepped back from him and put up her hand. “I have always done so, Dr. Rostami.”

“Did we really surrender?” he asked her.

“Collectively,” she said. “I would advise against it on an individual basis.”

He smiled weakly. “I missed your speech. I am sorry.”

“Here.” She handed him her pencilled notes. She had left the clean copy at Comms. “That is the gist of it, but I suppose it will be broadcast again at some point.”

He wrote her when he returned to his family in Farsia, telling her he had the pages laminated and intended to pass them down to his children. She didn’t mind that. It would have been embarrassing to see her erasures and chicken scratch turn up in a museum somewhere. That seemed unlikely to happen within her lifetime.

When she was at last alone again, she sat down at her desk and muffled her crying against the sleeve of her greatcoat. Not for long. Someone would be in asking more of her shortly. They had to continue the fight.

◈◈◈

“I didn’t want to mess up your dinner, you know?” said Corinne Santee, several years and several hundreds of miles removed from the surrender at Valvienne. She gingerly rested her stone arm on the table. Sometimes it broke things. The table-top creaked but held. “It’s not you, sir. I just… I’m not…” She looked away. “I know how I am. Sometimes.”

“You would not have ‘messed up’ my dinner, Corporal Santee,” said General D’Iver, icily. “I am terribly disappointed that you think so little of me, and of my associates. You have left it so late that I am incapable of introducing you. I do not appreciate it when decisions are made for me.”

“I’m sorry, sir,” Corinne said.

“Are you hungry, sir?” Maggie asked gently.

Corinne shrugged and scratched her nose with an articulated marble finger. “I dunno. I don’t have to. I don’t want to bug you.”

The General swatted both hands on the table and stood, “You are not bugging us, Corporal Santee! We have plenty of leftovers and it is a holiday tradition to serve them in the small hours of the morning.”

“I kinda broke into your house,” Corinne said.

“We are quite used to that,” said the General. “Would you prefer a cold sandwich with everything on it or something warmed up? I warn you, the bread may be stale.”

Corinne smiled at her. “I’m used to that. A sandwich is good. Your tree is nice. Is it still Yule?”

“Not according to the calendar, but we will hold it over a few hours more for you, Corporal Santee,” the General said. She turned on the tree lights on her way to the basement to bring up the food. Corinne applauded softly with appreciation.

You will have to stand for all of them, Corporal Santee, the General thought with a sigh. Though that is in excess of the duty you have already performed. You live near me, and you are too proud to care for yourself, so you will have to put up with me caring for you. I do not abandon my men.

The plowshare and the broken sword — along with the newly forged blade that was still being sharpened — made sandwiches and ate them in the dining room of Hyacinth’s house, where they did not throw broken things away.