There was a girl in the kitchen. She was dressed all in white. Her hair was white. Her skin was white. Her eyes were white. She had a great big white bow in her hair, and white boots with heels and buttons.

There were also colours and lines and hash marks and spots and shadows. Red, green and blue, and black. Sometimes white or pink or yellow, but not nearly as often as those others. He didn’t know if his eye had more trouble with red and green and blue and black, or if it just liked them better, like it liked the lines in the wallpaper.

The girl casually touched the handle of the pot on the stove, turning it so that it was over the counter instead of sticking out. She liked doing that. She would touch pot handles even if they weren’t sticking out, like maybe that was lucky or something.

She wandered over to the pantry and had a look in there. The pantry didn’t have a door, nothing in the kitchen had doors, so she didn’t have to move anything to look in.

She sighed. No marshmallows.

He knew she was looking at the cereal. She liked to do that too.

He tipped his head forward and took out his eye. No more girl. No more colours or lines or shadows either.

He put his eye back in. For a moment, it was all lines and colours and shadows. Then his eye wandered off to look at the wallpaper and he couldn’t look at the girl, but he heard her. Her voice cut back in as soon as the eye clicked into place.

…good cereal with the marshmallows. It’s always cornflakes. She peeked over at him and said, I’m going to do something about the cornflakes, Erik. She departed the room through the wall.

He had seen people go through the wall. Regular people. Because sometimes his eye didn’t see doors, it just thought there was more wall because there was mostly wall. But he knew there wasn’t a door there.

He also knew there wasn’t a girl there. But she wasn’t like the colours and lines and shadows. The colours and things had been there from the start, and they had been a lot worse.

Hyacinth had talked to him about that, and pieces of things disappearing and regular people walking through walls, even the weird shapes that crawled like bugs or grew like hair. That was all normal. He was adjusting to his eye and the eye was adjusting to him. All of that stuff was getting better.

Hyacinth didn’t say anything about people. The people had started to come later, flickering in and out, their shapes and voices, and they were getting worse. They stayed solid most of the time now, and he could see them walk into the room and leave it instead of just vanishing. Sometimes they still disappeared, but he thought maybe that was because they could and they wanted to.

They were the people he had seen in the basement when he was still really sick. He hadn’t minded about that then. Well, he hadn’t minded it any more than being sick and hurting and not understanding things.

Remembering it now, though, he didn’t like it.

Nobody else could see or hear the people and that was like he was crazy. He didn’t think he was crazy — he was pretty sure there really were people, even if they weren’t like real people or really there — but that didn’t make him like it.

There had been a lot of them in the basement. They talked a lot and they weren’t very gentle with him. They had been interested in him, and some of them tried to be nice (the fat woman and the man who limped), but they weren’t really like friends. It was like he was a kitten or something and they wanted to pet him. Or a new toy.

The limping man liked to hang around the kitchen too, but he left the pot handles alone. He liked the wooden spoon. That one particular wooden spoon. It had a big chip out of the middle but they still used it. It was good for dishing out spaghetti.

He would stand there with his hands folded and stare at it and smile. Sometimes he’d sigh, like he was appreciating a painting. Everything gets used in this house, he’d say.

He’d also said, to Erik, Don’t worry. You’re not crazy, you’re just broken. But like it was a compliment.

Erik was pretty sure he wasn’t crazy, but he wasn’t going to take the word of an invisible man who could spend hours staring at a spoon on the matter.

He was going to have to ask Hyacinth. She knew about the eye and she could talk. Milo knew more about the eye, but he couldn’t.

Uncle Mordecai was entirely out of the question. He knew a lot, but he didn’t handle things very well, especially if it was something about Erik being hurt, or something that might hurt Erik. Uncle, sometimes I see people that aren’t there and they talk to me, and sometimes they’re mad I can see them, might send him to bed for a week.

Hyacinth came back up from the basement. Milo was working on a toaster down there, as well as the radio. He was trying to make the radio go without metal, but he had no hope of doing that with a toaster. A toaster needed to get hot.

Given the metal, Hyacinth’s occasional assistance made things easier. Given the metal, it was also only a matter of time before the toaster got used up and Milo needed to make another one, but Ann liked toast and Milo liked making toasters.

She stirred the noodles in the pot. She did not notice the pot handle had been adjusted.

“Auntie Hyacinth?” Erik said.

“Yeah, hon?”

“I can see the people from the basement. With my eye.”

She turned to look at him and rested both her hands on the edge of the counter behind her. “You what now?”

“The people in the pictures in the basement. In… in that place with the glass and candle.” He made the shape of the shrine with his hands. “I see them. I saw them when I was really sick in the basement. Now I see them again, but only if I have my eye.”

“You’re seeing the Invisibles?”

“Yes.”

“With your metal eye?”

“Yes.”

“Seeing them? They don’t just talk to you like usual?” Although that was weird as hell, it was usual, for Erik.

“They talk sometimes. When it’s just talking, I don’t need the eye. But if I see them and they’re talking and I take out my eye, then I can’t hear them or see them.”

“Milo, what the hell did you do?” Hyacinth muttered.

As if he could tell her: Oh, yeah, I added a god spring. Just figured it out. I thought Erik would like to be able to see who he’s talking to. What? Is there a problem?

“Is it like the weird colours and the sounds, Erik?” she asked him. “Is it going away?”

“No. I’m seeing them better.”

It was not entirely impossible that Erik was crazy. In some way. Erik had brain damage. It was getting better, but it could get worse. A seizure, or a stroke, something brought on by the damage itself that caused more.

Or something the eye had done to him, because she’d trusted Milo with it and let him build the damn thing from scratch with no oversight or supervision.

…Erik was wearing it in his face and it was hooked up to his brain. Oh, gods! She sort of wanted to have him take it out right now, and maybe never put it back in. They could get a normal one from a store.

But he didn’t seem worse. He was improving with words and memory and even reading and writing (though that came painfully slow). His speech was a little slow, too, especially if it was a big word he wanted or he was excited or upset, but he was faster than he had been and you could understand him. He remembered everyone in the house, and what to call them. He didn’t get lost doing simple tasks, or even complicated ones.

He wasn’t seeing things very well and he couldn’t always track motion or focus, but that was because his metal eye was screwing with the whole system. When he had it out, his real eye recovered quickly and behaved like normal. She had checked him on that this morning. He still couldn’t quite follow her finger with it in, but he had no trouble with it out.

And the gods did talk to him. They told him things he had no way of knowing otherwise.

But the gods talked to a lot of people — maybe not like they talked to Erik, but they could be spoken with. The gods made deals with people. They slipped into coloured bodies and walked around and then anyone could talk to them. Talking to the gods was ordinary, practically.

Seeing the gods was unheard of. At least she’d never heard of it.

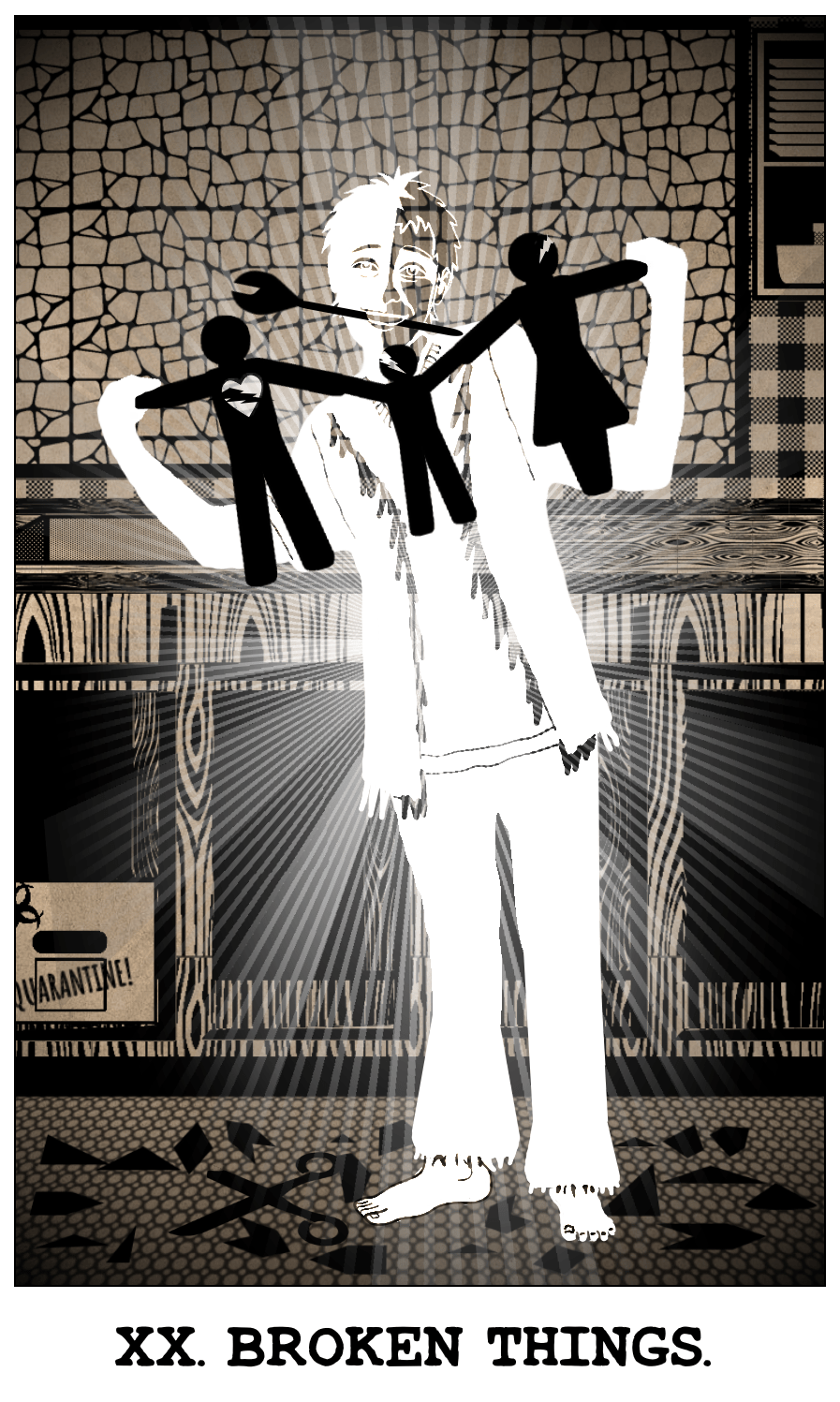

There were pictures, icons for shrines and individual worship and prayer. But they were copied from each other or drawn from descriptions given by the gods themselves. Cousin Violet said she was a little girl who was all white and she had a big bow in her hair, but nobody had confirmed this by sight.

To the people who called them, the gods were formless — balls of energy and intent. Voices, personalities, but not bodies. When they walked on the earth, they looked like whoever they were wearing.

Presumably they could get around without wearing people and they were constantly meddling in things, but you couldn’t see them doing it.

It was not impossible that Erik was crazy, but it was not impossible that he was seeing the Invisibles either.

“Erik?” she said. “When you see them, what sorts of things do they do?”

“The girl who’s all white likes to move things, but only a little. She turns the pot handles in. One time there was a pencil on the floor and she moved it a little and later Maggie ran through the kitchen and I think she would’ve fallen if it didn’t get moved.”

“That’s Cousin Violet,” Hyacinth said, nodding. That jibed with everything she knew about Cousin Violet. “She’ll change small things and sometimes make big things happen. Nice things if she’s feeling nice. Bad things if she isn’t.”

“Cousin Violet,” Erik said. He nodded too. He thought he’d heard the name, or he used to know the name. Maybe he knew it for a little while and then he forgot it, that happened to a lot of the things he’d learned when he was still pretty sick. “She likes to look at the cereal and talk about it too.”

“Cousin Violet likes cereal,” Hyacinth agreed. She had certainly asked for it when she was running Erik’s mouth for him.

“The man who limps doesn’t move things, but he likes to look at things. He likes the spoon we use for the spaghetti, and the broken mug and the plates with cracks. When Ann broke the pink plate and threw it out, he cried.”

“That’s Lame Anthony,” Hyacinth said. “He likes broken things.” She had heard him out of Erik a few times too. Mainly that he was sorry about all the others, but there were just too many and he couldn’t keep them away.

“He said I’m broken,” Erik said, looking down.

“Well, that means he likes you,” Hyacinth said. She sat down next to him at the table and she took hold of his hand. “Hey, you know I’m broken, too, don’t you?”

She didn’t ask him if he remembered. Erik was properly sick of people asking him if he remembered.

“You’re not, though,” he said.

“Sure I am. I’ve got a steel plate holding me together. Here, you can feel it.” She leaned down and she touched the left side of her head.

Erik obligingly felt there. There was a raised patch with straight edges and sharp corners. David had mended her neatly.

“I got hurt in the head when I was just a kid. I was a little older than you. I guess I told you about it a couple times, but maybe not very much. I don’t really like talking about it. It kinda sucked.”

She had told him more than a couple of times, she was sure of it, usually when he was crying. Either in pain or just frustrated and confused. She was also pretty sure he wouldn’t remember it. He had been in a lot worse shape than this.

“Can you tell me what you know about it?” she asked. “I know the gods are always telling you stuff. I’ll fill in the blanks.” Again, this was better than asking if he remembered.

“You had a schedule,” Erik said. “Because it’s easier when there are times for things.”

Hyacinth nodded. Technically, she had a chart. It had been Barnaby doing it for her so naturally it was a chart. She had been able to read all right. The chart was… well, maybe not enough, but it helped and Barnaby didn’t have to be in the house for it.

Barnaby was only in the house about fifty-percent of the time back then. Technically, he had been married with his own house. For a little while.

When he remembered to check up on her, (which he did, occasionally) if she’d been doing the chart she got a chocolate. She had found that a little bit patronizing, but she had liked the chocolates. They were imported.

“Hazelnut crèmes,” Erik said.

Hyacinth nodded again. Someone she could not see had just whispered into Erik’s ear, or brain, or wherever he got whispers, about the chocolates. “Erik, did you see who told you that?”

“No. I just know it.”

“Do you know what it means?”

“Sort of. It was for being good. There were stars on the paper so he’d know.”

“My schedule was on a chart. I’d put a star when I did something. It was Barnaby, so he knew if I really did the things or if I was just putting stars. I think he would’ve known without stars, but I had to put marks so I’d know what I’d done.”

“You forgot stuff?” Erik asked.

“Yeah. Lots of the time. Clothes especially. I didn’t like clothes.”

“The buttons?” Erik said. He’d had a lot of trouble with buttons. Lining them up right and getting through all of them. He was still a bit suspicious of them.

“Well, sometimes, but just having them on.” She glanced up at the ceiling. “I kind of forgot I needed clothes and I wouldn’t believe people when they told me I did. I got mad about it.”

She still didn’t really think she needed clothes, just that it was something everyone agreed upon at some point and they were unwilling to change now.

“I was mad a lot,” she said. “About not understanding things and everything being hard. You were really sweet to people, Erik. I was a hellion.”

“I was mad a lot too,” Erik said. “I said a lot of mean things.”

“Not like I did,” Hyacinth told him. “Maybe you wanted to, but you didn’t have words. I didn’t lose my words. I lost my filter.”

“Your filter?”

“Yeah. You know how sometimes you just say what the gods tell you and you don’t really mean to and people get upset?”

Erik nodded with a pained expression.

“Okay, imagine like that, but only your own thoughts in your own head. And all the time. If I thought it, I’d say it. If I wanted to do it, I did it too. Even if I knew I shouldn’t.”

“You said some things to some ladies,” Erik said.

Hyacinth winced. Another god-whisper, and this one wasn’t something innocuous like the chocolates. “I really hope you don’t know too much about that, Erik. I’m sorry if you do. I couldn’t help it then, but it’s really embarrassing now.”

“Just your mom and dad were really mad,” Erik said. Now he winced. “They made you go away?”

“I went to live with David,” she said quickly.

They had wanted to send her to, well, not David. An actual asylum instead of just an incredibly lifelike simulation of one. The kind where they don’t ever let you out.

“He… Well, he didn’t really know how to take care of me, either, but he put up with me. And he came up with a few good things, but I think that was probably by accident. What I needed most was time to heal, and not everyone screaming at me all the time.”

Screaming still, just not at her. Well, not about her.

Not about her being a bad person.

Not about being the type of bad person who needs to be put in an asylum, not that type of bad person, just a horrible, ungrateful little girl. She could handle that. Besides, David called everyone horrible.

“But they were your mom and dad,” Erik said. He couldn’t get past that. He didn’t really have parents like that, but he knew they were supposed to take care of you. Not yell at you and then send you away forever, especially when you were hurt.

“I was pretty awful to them,” Hyacinth said.

She shook her head. If Erik had been that awful, or even worse than that awful, she wouldn’t have sent him away. She didn’t want him to think that they’d only taken care of him because he’d been nice.

“No, but it wasn’t that,” she said. “They didn’t really get that I was hurt. They wanted me to be normal right now, and I wasn’t. And they didn’t like that. You have a lot better uncle than I had a mom and dad. I had a pretty crummy mom and dad. I was lucky I ended up with someone better.”

David, better than her mom and dad. Horrifying, but undeniably true.

“Do you think my uncle wanted me to go away?”

“I am certain that he never did. And don’t you ask him that, because he’ll run off. He wouldn’t like knowing you even imagined he’d send you away.”

“I didn’t imagine it, I just got scared of it,” Erik said. He turned his head away.

“I had rotten parents,” Hyacinth said. “You have an excellent uncle.”

He was maybe not too sound in the whole mental health department himself but, damn it, at least he was trying. He didn’t scream at Erik or threaten or punish. He wasn’t like David and Barnaby, who just didn’t care about her being bizarre. He cared and he helped. He would randomly quit doing it and hide, but that was better than anything she’d had.

…All right, so maybe he’s not worse than David, but I could still do with him being a little less stupid.

“I’m sorry you found out about my parents, Erik,” she said. “I just wanted you to feel better about being hurt. I was hurt too. I’m still a little weird, but I do all right, don’t I?” She smiled.

“You’re really great at everything,” Erik said sincerely.

“Oh, honey, I’m not!” she replied with a laugh. She shook her head. “No. Thank you for saying it. Thank you for thinking it. But I’m broken like everything else in this house. That’s why we have Anthony in the shrine. Lame Anthony knows that you don’t throw broken things away, and so do I, and so does your uncle. Maybe something like a plate, okay, but not people.”

“So it’s okay if I see gods?”

“Erik, it’s okay if you don’t see gods and you’re completely off your rocker! Either way, we will figure out some way to cope with it.”

“I don’t think I am crazy, though,” Erik said, frowning.

“Honey, I don’t think you are either. I think it might be a little bit easier if you were crazy. Gods are more dangerous than crazy.”

Erik nodded. “Sometimes they’re mad at me when they think I can see them. I don’t know what to do about it. I don’t talk to them because I’m scared if someone sees, but sometimes they see me looking.”

Hyacinth frowned. “What sorts of things do they do when they’re mad?”

“Usually they just go. I don’t know if that’s mad or scared. But sometimes they talk to me. They say ‘Do you see me?’ but like they don’t like it. I don’t ever say yes.”

“Definitely don’t say yes,” Hyacinth agreed. “Especially if they’re not happy about it. Do they ever act like they’re going to hurt you?”

He shook his head.

Of course, that doesn’t mean that they won’t, thought Hyacinth.

“You used to see them without the eye?” she asked him. “In the basement?” If the problem was the eye, Erik could do without it (or they could get a normal one from a store), but she didn’t think that was it.

“All the time,” Erik said. “I stopped talking to them because it was hard and I was tired and they kind of went away.”

“You ignored them and they went away?”

“No, not really away. They like to talk to me. Sometimes I just know things but sometimes I hear them. When I stopped talking to them, it stopped being so many and all the time.”

“They notice you noticing them and then they pay more attention and there’s more of them?”

Erik nodded. “Yeah.” That was it exactly.

“And you only just started seeing them again so you’re noticing them a lot more now?”

“Yeah, I think I am.” He hadn’t thought about it that way, but yes. He stared more because they had come back, and he was worried about it.

“Do you think you can get the hang of ignoring them again?”

“I can try to,” Erik said.

Hyacinth nodded. “Let’s do that. Maybe it doesn’t matter if you see them as long as they don’t see you seeing them.”

“I think Anthony and Violet know I can see them,” Erik said. “They talk to me and they say my name.”

“Well, Violet knows everything, I don’t think we’ll fool her,” Hyacinth said. “And I’m certain Anthony won’t hurt you. Are there any others you see a lot?”

“The fat woman with the apron and the little black man. Sometimes he goes into the oven. Then he’s orange.”

“Hester Carthage and Iron John,” Hyacinth said. Two more faces from the shrine. “Do they know you can see them?”

“They know I could. I think they’re not sure now.”

“I don’t think they’d hurt you, either, but don’t let on you can see them. I think the fewer Invisibles who know about you seeing them, the better. Do you ever see a short black woman with pale blue hair?” That was Auntie Enora. She was in the shrine too. “Not black like Iron John. Not short like Iron John either. Normal-sized-person short. Black like Sanaam.”

“Sanaam?” said Erik.

“Maggie’s father.”

“Yes!” said Erik, relieved. Oh, he thought maybe he forgot a person again. No. Just the name. “No. I mean, I haven’t seen a woman like that.”

“She probably won’t hurt you, but definitely ignore her. She’s really curious and she meddles.” Hyacinth had made her acquaintance personally.

“Okay.”

“What about a tall black man with a top hat with a green feather?” That was the last picture in the shrine, one that was there for appeasement, not invitation. She hoped like hell the Baron wasn’t hanging around the house.

Erik winced. Yes. It had only been once and he had been really, really sick, but he couldn’t forget it. The man touched him and made him nothing. Not asleep or fainted, or darkness and confusion. Nothing. A hole in his existence that was not loss of mind or memory but like someone had snipped the thread of his life and then graciously allowed him to pick it up again later.

But he didn’t want to say that and he didn’t want to talk about that and he didn’t want to remember that. He said, “No. I don’t like the… picture, it’s… scary, but I never saw him.”

“If you ever see that man you take your eye out,” Hyacinth said. “And you don’t look where he was in case you can still see Invisibles without your eye. Leave the room. Leave the house. Don’t even tell anybody. Just go. It’s better for you to scare the hell out of us than for that man to figure out you can see him, okay?”

He nodded rapidly. “Yes, Auntie Hyacinth.”

“Okay, good.” She took a deep breath and sighed it out slowly. “I think we’d really better not tell your uncle about this, okay, Erik? Maybe try not to talk about it too much at all, in case the Invisibles are listening, but definitely not your uncle. You know?”

She hoped she didn’t have to say why. Her own opinion was that Mordecai was being a useless, self-indulgent fool, but she wouldn’t like to say that to Erik.

Erik nodded. “No. I know. It’s why I asked you.” He shrugged. “And Milo can’t talk.”

“Yeah. Darn that Milo.” She really wanted to interrogate him about Erik’s eye. Milo, if you invented a god spring, you would tell me, right? Right?

But that would totally short out his brain. Milo had a real hard time with “why.” Why is Erik seeing gods? directed at him as if it were his fault, would get her no kind of viable response.

Maybe she could write something more gently worded on a piece of paper and let him take it up to his room for a short essay, but she didn’t expect to get a solution out of him that way, or any way. She really didn’t think it was the eye, and there was nothing Milo or any of them could do about gods.

“Will you keep an eye… I mean,” she covered her mouth and looked aside. Her damn mouth still got her into trouble. “Will you kind of pay attention and see if not looking at them and not talking helps anything?”

Erik nodded. “I think it will, but I’ll say if it helps or it doesn’t help. Auntie… Hyacinth?”

He was looking pained again.

“Hm?”

“I’m glad you don’t throw… broken things away. I’m glad I was here and not… someplace else so you could… fix me.”

“Oh, honey.” She crouched and hugged him. “I’m glad you were here too. I’m glad I knew enough about what you needed to help you. We were both lucky that way.”

“I’m sorry they tried to… throw you away. I won’t ever do that.”

“Of course you won’t,” she said sternly. “Because you are a decent human being. I don’t throw away easily, Erik. I crawl out of trash cans like a cursed object. You do that, too, if anyone ever tries to throw you away. You come back and kick their ass.”

Erik smiled. “I’ll try. I’m kind of small.”

“Well, maybe grow up a little first. I’ll try and slip in some ass-kicking lessons when your uncle isn’t looking.”

“I think he might like them better if you don’t call them that.”

“Your Auntie Hyacinth doesn’t mince words, Erik,” she said primly. She stood. “I think your Auntie Hyacinth may have also burned dinner, by the way.” She had been sitting and talking instead of stirring, and that had been quite some time.

“Uh-uh,” Erik said. “Cousin Violet blew out the stove.”

When she checked, this was indeed so.