She was barefoot and clad in a white chemise that the rain had done its level best to make transparent. Her developing figure was, while not impressive, certainly enough to look indecent. The darker patches left nothing to the imagination. Her hair hung down her back in a single limp braid. She was not shivering. She had gone numb.

“Young woman, where are your clothes?” the man in the tailcoat demanded of her.

“I don’t know,” she answered gravely.

“You don’t know?”

“I’m here to see Barnaby,” she said.

“Mr. Graham is indisposed.”

“Oh, that’s too bad,” said Hyacinth, dripping with sarcasm as well as simply dripping.

“Arthur, who is it?” came a voice from within.

The man in the tailcoat sighed. “My name…”

“Barnaby, he won’t let me in!” said the girl.

“Hyacinth?”

Barnaby Graham appeared. He was a sandy-coloured blond who wore his hair a little bit long and combed back. His eyes were pale grey and not terribly incisive — somewhat unfitting for a state augur, who should either be piercing or blind. He was dressed for dinner, in a dark jacket and tie. He was wearing one glove.

He removed the jacket and bundled her in it. “Hyacinth! You’re supposed to have a dress on!”

“I forgot,” she said.

“Oh, dear. Oh, dear. Oh, dear.” After a brief glance up and down the street, to see if police intervention was pending, he dragged her inside. “Well, what is it? What happened?”

There was a good fire going in the main room, and some wingbacked chairs suitable for brandy and cigars. He put Hyacinth in one of them. She promptly ruined the upholstery. In fact, she had done quite a job on the carpet as well.

“He’s shut himself in again,” Hyacinth said.

“Barnaby?” Hyacinth saw a single white hand with red lacquered nails resting on the drawing room door. “Who is it?”

“It’s David’s girl,” said Barnaby.

“Oh, David again!” said the woman in the drawing room. She slammed the door.

“He’s been going down all week,” said Hyacinth. “But, you know, sometimes he doesn’t. But he’s hardly said two words today. No. He called Madame Carlotta a vacuous cow. That was at breakfast. He said, ‘Madame Carlotta, you are a vacuous cow.’ That’s seven. And then he hasn’t said anything since.”

“I suppose Madame Carlotta has gone?” said Barnaby.

Hyacinth nodded. “And Siegfried left when he started playing the album.”

“Oh, the composer,” said Barnaby. He was surprised that one had lasted this long. “What about… What was his name? Gavin?”

“Gavin’s quit.”

“Of course he has. And there’s nobody else?”

“No, Barnaby. Of course there isn’t. Why else am I here?”

Barnaby sighed. Well, she was honest. Though, in Hyacinth’s case, maybe you couldn’t count that as a positive. She seemed to enjoy being upsetting. “All right, well, I’ll come back with you. We’ll get him sorted. Arthur, will you get us a taxi?”

“My name is Andrew,” said Arthur.

“Andrew?” said Barnaby. “What have you done with Arthur?”

“Nothing for at least seven years, sir.”

“Well, tell Arthur to get us a taxi!”

“You’ve got the name wrong, Barnaby,” Hyacinth said. “You always get it wrong.”

“Well, it’s only because I don’t care!” said Barnaby.

◈◈◈

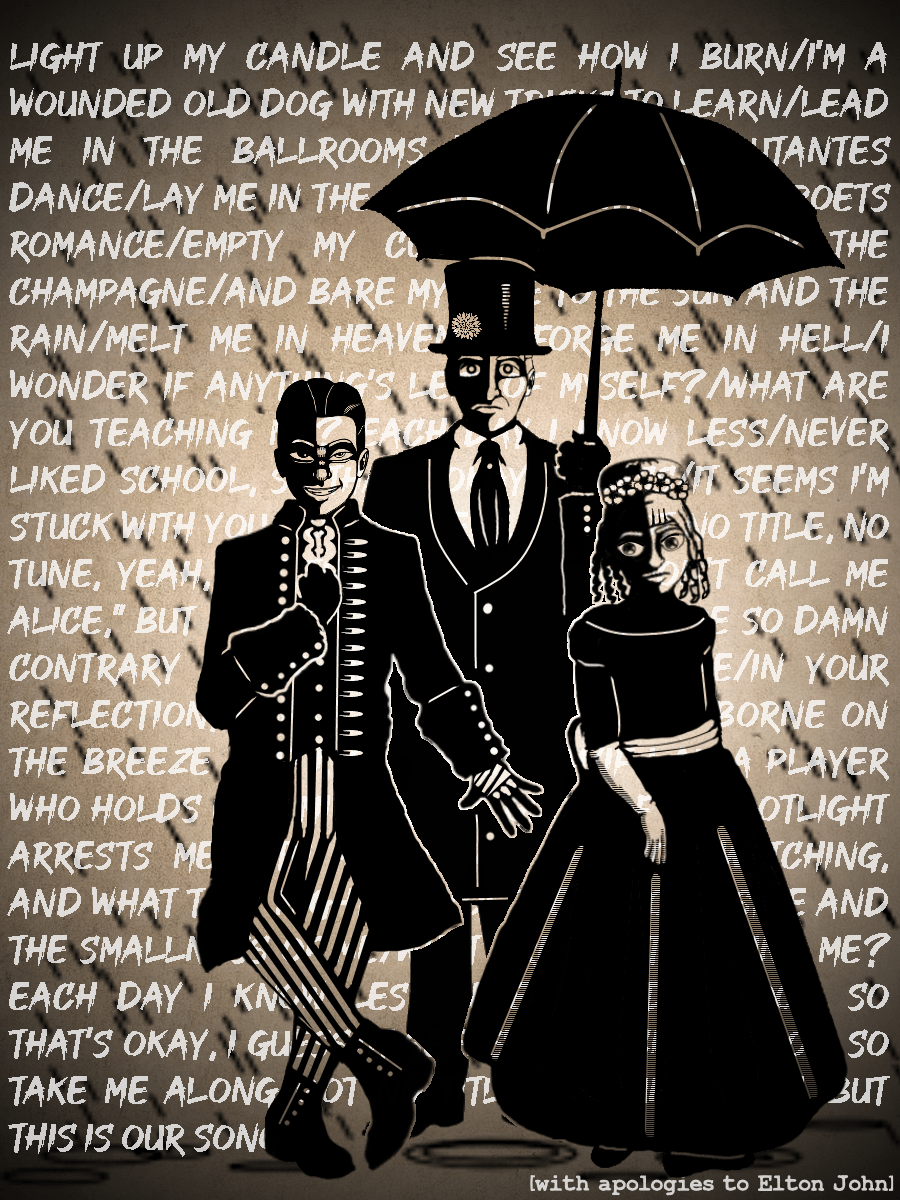

The taxi was black. The horses were black. The night was black and wet and chaotic. Hyacinth still lacked a dress and shoes. Barnaby had put on a raincoat and a top hat and was holding an umbrella over her.

From the top window of David Valentine’s townhouse, scant notes and words were drifting down.

“‘Candle in the Wind,’” said Hyacinth.

“So he’s been through it once already,” said Barnaby.

It might’ve been worse to hear silence.

It was never good to hear David indulging in his favourite (?) album, but at least it meant he was coherent enough to set up the cylinders and apply the needle. If he’d done it only a couple songs ago, he might be reachable.

“Hyacinth, come on.”

She had her hands over her ears. “I hate it,” she said.

“I know. But he won’t stop unless we stop him. Come on.”

It was louder inside, though still muffled. He had the door closed (and certainly locked).

They forged bravely on, hands over ears and eyes winced narrow, climbing the stairs in tandem. David’s study was at the top.

The volume was painful and the quality of sound was not good. Cylinders did not have high fidelity, and what they did have suffered when you played them loud. Sometimes you had to wonder if David actually liked his favourite album.

Barnaby martyred himself and spared a hand to rattle the door. “David! Come on, David!”

David turned it up louder.

Barnaby gestured to the doorknob. “Break it, Hyacinth. David shouldn’t have doors that lock, anyway.”

She winced and put both her hands on the metal. “We have to lock the kitchen, Barnaby.”

The lock and the hasp on the kitchen door were ironwood, which was safer than actual iron around David. Items which David might be disallowed on occasions such as this were kept safely inside. All the scissors, for instance.

“I know. Apart from that.”

“Don’t look at it,” she said. Barnaby turned his head away. Hyacinth shut her eyes. “Abraca-fuck you,” she muttered. She was still doing verbal magic, and that annoyed her. The swearing was a concession to the fact (and David thought it was funny).

There was a bright flash, a crackle, and the doorknob fell to the floor in two glowing pieces. Barnaby shoved open the door and went in.

David was sitting backwards in his chair with his arms draped over the back and his black hair hanging down like a string curtain. His left hand was dripping red and full of glass. The mirror in his dresser (he didn’t have a desk, he had a dresser, with many little secret doors and gilt details) was starred in the centre and scattered in pieces.

“Oh, David, what a stupid thing to do!” said Barnaby. He lifted the needle from the cylinder and ended “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road” just as it began.

David lifted his head. His eyes were ringed and streaked and furious. “Put it back on!”

“No,” said Barnaby. He removed the cylinders and pocketed them. He laid his handkerchief on the dresser and began placing the shards of broken glass inside it. “When you shatter your reflection, you endanger your soul,” he said.

“What soul?” said David, looking down.

“You really must have one,” Barnaby said. “What else is damaged about you?”

“His brain,” Hyacinth said.

“Hyacinth, I’m surprised at you,” Barnaby said.

“I should know, shouldn’t I?” Hyacinth said. “Barnaby, what about his hand?”

Barnaby was still gathering the glass. “You’ll see to that, won’t you, Hyacinth? You know where everything is. We’ll put the pieces in running water,” he told David. “I think the gutter will do for that tonight.”

Hyacinth groaned and rolled her entire head sideways. She stamped off down the hallway.

“I was thinking of slitting my wrists with them, actually,” David said behind her.

“Don’t be absurd,” said Barnaby.

She ducked into her bedroom and changed into a dry chemise. Dresses were not required in the house, but naked was not allowed out of her room. This was a compromise which — after many screaming arguments with her parents — she was willing to abide

Except on those rare occasions when she forgot.

There were bandages and iodine in the upstairs bath, and she collected them. There would be tweezers in the study. David groomed himself mercilessly.

There was also a drinks cart in the study. Barnaby had made done with the mirror and was assembling some.

“I’ll have a gin and tonic,” Hyacinth said. She pulled up a chair and sat down next to David. She took his hand. He allowed her to move him like a doll.

“You will have a club soda,” Barnaby said. “Put the glass in the hanky, Hyacinth, not on the floor.”

“Alice can have what she wants,” David said, muffled.

“Don’t call me that,” said Hyacinth.

“Alice is twelve,” said Barnaby.

“Don’t call me that!” said Hyacinth.

“Hyacinth, if you want a gin and tonic, you can make it yourself,” Barnaby said.

“I will,” she said. “Here, David, this stings.”

He did not react.

“Here, David, drink this.” Barnaby handed him the glass. David’s hand came out and then disappeared behind the curtain of his hair.

“There is too much Alexander in this brandy,” David said. He handed back the glass by the rim.

“It’s the usual amount,” Barnaby said.

“Put a shot of vodka in it,” Hyacinth said.

“Gods!” said Barnaby. “What do you get up to in this house when I’m not here?” Nevertheless, he did so. It was accepted.

“David, what if we go out tonight?” Barnaby said.

“I won’t go out!” David said. “I won’t go where I’m not wanted. You all hate me! You despise me! You don’t want me to have my music…” He sobbed.

“No,” said Barnaby. “What about a movie?”

“I don’t want to go to a movie!” said David. He peeked out from behind his hair. “What’s playing?”

“Journey to the Moon, I think.”

“I’ve seen it.”

“Yes, two times. Loved every minute of it, as I recall. Threatened to shoot the projectionist when they wouldn’t spool it again.”

“I did not threaten to shoot him. Why do you always make me worse than I am? I said he should be shot.”

“You said you’d order it done.”

“Why do you even bother with me? Why do you take me places if I’m so awful?”

“David, it’s just the movies,” Barnaby said. “It’s not like I’m taking you to church.”

“I can’t go to the movies,” David said. “I’m hideous.” He flipped his hair back, exposing his face.

His eyeliner had run rampant. There was a little bit of powder clinging in streaks which made him alternately pale and hectic. The lines of the merger where the gold had been used to replace his nose were jagged and uneven when he didn’t hide that with foundation. His blown pupil added to the general effect. He looked like the broken mirror.

“Well, you are a bit ghastly, but we’ll soon get you sorted,” Barnaby said. “Listen, we’ll get dressed up all nice like it’s the real theatre. You and me and Hyacinth. I’ll have some of your things, if you don’t mind. You can have a dress if you want one.”

“No,” David said faintly. He set his empty glass aside. “My purple frock coat. And the dark blue waistcoat with the stars.”

“I’ll fetch them. Hyacinth, get him into the bathroom and wash his face. Fix his eyes.”

“No! No mirrors!” David cried. He flung his arms over his face. The ragged end of the bandage fluttered theatrically in the breeze.

“You’re an ass,” said Hyacinth. She pulled the bandage tighter and tucked in the end. “I’ll bring you a dish of warm water and a rag.”

“Bless you, dear child,” David called after her.

◈◈◈

He still wouldn’t have mirrors, so she had to do his eyeliner for him. It was fiddly and annoying, though he was preternaturally still. She worked with her tongue probing the corner of her mouth.

“I should give you more eyebrows,” she said. “You’ve been acting a fool, you should look like one.”

“Thank you for saying it instead of doing it, dear.”

She handed him back the pencil. He pocketed it.

“Now, Hyacinth,” he told her, index finger raised, “if you are a very good girl, and you keep your dress on all night, I shall buy you a pony. What about that?”

“I don’t want a pony, David,” she replied.

“Not want a pony? Every little girl wants a pony! Where’s your sense of whimsy?”

“I’m sitting on it, David.”

“You are a bitter old woman wearing the body of a child,” he told her. “You’re an imposter! You and your gin and tonic. What if I want a pony? What then?”

She sipped her drink. “I don’t think you should have a pony, David. I think you would only find some way to kill it.”

“Kill it? Why would you say such a horrible thing?”

“You killed Admiral Feathers.”

“I did no such thing!” cried David. “Admiral Feathers fell ill!”

“You were always feeding him cough drops,” Hyacinth said.

“Admiral Feathers liked cough drops!”

“You certainly liked feeding him cough drops,” Hyacinth said. She sipped. “He rattled when we put him in the coffin.”

“Oh, sharper than a serpent’s tooth!” said David. He turned his head aside and let his hair fall over his face.

“What’s your serpent’s tooth been doing to you now?” said Barnaby. He was trying on vests. David’s “I’m so fat and hideous!” collection fit him rather well.

“Oh, Gray!” said David. “Hyacinth says I can’t have a pony!”

“You mean in the townhouse?”

“Why not in the townhouse?”

“You can’t have a pony, David,” Barnaby said.

“I can have several ponies if I want them,” David said. He adjusted his cuffs. “I can have a pony in every room. Hyacinth, let me do your hair.”

“My hair is fine,” said Hyacinth. It was wet and the braid was fraying in multiple directions at once.

“I think the police might have something to say about that many ponies in a townhouse,” Barnaby said.

David turned on him, “You told the police about my alligator, didn’t you?”

Barnaby became suddenly contrite. “Nooo,” he said, tapping his fingertips together.

“I really loved that alligator,” David said mournfully. He slipped the tie out of Hyacinth’s braid and began combing his fingers through it. “He was a dear creature. Completely tame. Now if I want to see him, I have to go to the zoo. But I can’t go to the zoo, now, can I?”

There was a bottle of hair oil in the dresser. He applied a liberal amount.

“My hair is fine,” Hyacinth intimated through clenched teeth.

“I don’t see how that’s my fault,” Barnaby said.

“You dared me I couldn’t steal a penguin!”

“I believe I said you shouldn’t steal a penguin.”

“Oh, it’s practically the same,” said David. There were bobby pins in a drawer and he put some in his mouth. He began rolling Hyacinth’s hair into little tails. “How is Lord Crumplebottom, anyway? Have you seen him lately?”

“He’s got married,” Barnaby said. “They have an egg.”

“Penguins get married?”

“Apparently.”

“Poor creatures.” In another drawer, there were hair ornaments. He added a sprig of fake flowers to his design. “There now, Hyacinth. Isn’t that much better?”

It was nest-like and complicated, with a few spiral curls hanging down. “I hate it,” she said.

“Let’s pick out a dress you hate that matches!” David said, clapping his hands.

It buttoned up the back. All of her dresses buttoned up the back. It wasn’t that she couldn’t get out of them, but it was a little more complicated to do so and it gave her a minute to remember if she wasn’t supposed to.

This one was an off-the-shoulder number in pale blue shiny stuff that dragged on the ground. David added elbow-length gloves and blue silk slippers. She hated it more than her hair.

It was also completely impractical for the rain. David insisted upon carrying her over puddles. He certainly wasn’t going to put his coat down.

They got in a taxi. The taxi was black, the horses were black, the night was black. They were not black. They were like circus people.

Barnaby had even traded his black umbrella for one of David’s green ones. He was wearing an orange plaid vest and a fake pink carnation in his top hat. David was resplendent in his purple frock coat and dark blue waistcoat with the stars, and a pair of striped trousers. Hyacinth was an involuntary fairy princess.

The three of them together had much the same effect as David in one of his dresses.

Hyacinth was annoyed.

David waved at people.

The movie theatre was playing a double feature, Journey to the Moon and Werewolf Murderer. These were self-explanatory.

Hyacinth thought the moon men were all right, but the werewolf left a lot to be desired. His fur buttoned up the back, like her damn dresses. It was like the movie people didn’t even care.

She felt a little sorry for him. He seemed to be apologetically killing all those pretty ladies, merely because he knew it was expected.

David kept shrieking and grabbing her arm throughout the whole thing, of course. David was poorly constituted for horror films.

“Oh my gods, never again,” he said, recovering on the bench outside. “Those poor girls. That awful music.”

Hyacinth had quite liked the music. It had been better than the werewolf, anyway. Deep and genuinely spooky, with occasional whimpers and screaming. All from a piano and a ’cello.

“We didn’t have to stay for the second one,” Barnaby said. “Not all of it.”

“But didn’t you want to know if they got him?” David said. “Don’t you feel better knowing they got him?”

“You have to kill a werewolf with a silver bullet,” Hyacinth said. “They only burned down his house. He’ll be back.”

“Oh my gods, do you really think so?” David said.

“He could be out there right now, David,” Hyacinth said, grinning. “Do you think you’re pretty enough to get killed by a werewolf?” She put up a clawed hand and reached slowly towards him from behind.

“Hyacinth!” said Barnaby.

“You’re a horrible child,” David said, weeping. “Horrible. Horrible!”

“Oh, David, you could see the buttons!” she replied.

“David, would you like a glass of water?” Barnaby said.

David brushed back his hair. “I would like a Brandy Alexander,” he said.

They gave her a fifty-sinq note and the umbrella and pointed her in the direction of an arcade.

“Go thou, Thankless Child,” her erstwhile guardian admonished her. “Spend my money with impunity. I don’t mind if I ever see any of it again.”

A fifty-sinq note was patently useless at an arcade. She walked to a soda fountain first and broke it with the aid of a strawberry float. Then she fed the five and singles into a change machine and tucked the tens down the front of her dress.

The arcade was loud and bright and cacophonous, with many machines vocally and musically demanding attention at once and constant coloured light bulbs blinking on and off.

There were some kids inside, not kids her age, not at this hour, but teenagers on dates. Some of them were drinking out of flasks. Some of them were making out in the sheltered places, in booths and behind booths and in corners. She wasn’t impressed with them. It was no more than she had seen adults doing at parties, sometimes with even less decorum.

They were mostly using the test machines. The Love Test and the Strength Test and the Is It A Perfect Match?

She decided she would have all the minifilms first. They had the most entertainment for the least effort. Maybe Barnaby and David would be back by the time she was done.

Maybe.

She watched all of them, clockwise, making the sweep of the entire room. Even the dirty ones, though she had to climb up the side of the machine and hang onto the viewfinder to look in.

She watched a pie fight. She watched a man wash a horse. She watched a woman dancing with two large fans. She watched a fox pushing a goose in a pram. She watched a man and a woman making love on a couch. She watched a monkey smoking a cigarette. She watched a lion jump through a flaming hoop. She watched a garden party where no one had any clothes on for some reason. She watched naked people playing volleyball.

You know, I don’t know why everyone gets so upset about me having a dress on, she thought.

Barnaby and David didn’t show, so she went on to the automatons.

David had rather ruined her for automatons. He made them, when he was in a mood for it, but good ones. There was a small collection at the house. They were done all in metal and most of them played music. Her favourite was a silver swan that ate fish and played “The Beautiful Blue Arles.” (He said that one was a copy of something he’d seen somewhere: They wouldn’t sell it to me and I wanted one.)

These ones were finished in cloth and rubber and they clicked and chattered like chipmunks. The ones that played music did it badly, little snippets on cylinders, sometimes voices or sound effects. There was a puppet show and a magic act — not real magic, of course — and a clown that just sat there and laughed. (That one was particularly disturbing. She didn’t even put money in that one. She just walked past it.)

Next, she did the games. There was pinball and ring toss and wire mazes. There were games where you put a coin in to see if you got more coins. (She purposefully failed those. What did she want with more coins?)

They had a Roll-A-Dance on a little stage in the centre of the arcade. You picked the music, the band organ played it, and you had to keep up with the steps on the paper. There were bright lights and a prohibitive amount of magic involved.

Most of the Roll-A-Dances she had seen were broken. This one seemed to function reasonably well, but she wasn’t any good at it. She kept treading on her dress and she didn’t like the noises it made when she missed a step. She had undone her top two buttons with absent frustration before she remembered she wasn’t supposed to.

“Stupid princess dress,” she muttered. She kicked the machine. It booed at her, a deep sound from a metal bellows.

A red and yellow sign lit up with a ping: Try Again?

“Obnoxious machine,” she added. She put her hand on the coin slot and fused it shut. “Abraca-fuck you!” Ha. Let’s see ‘em fix that!

The teenagers were thinning out. There were some lost-looking people wandering in from the streets, drunk or just tired and looking for a place to stay dry, mostly men. One man in a filthy raincoat was obsessively watching the naked volleyball film with his hands in his pockets. She gave him a wide berth.

Now nobody was doing the test games, they didn’t offer long enough respite.

She did them. She was a Hot Tomato! Or, alternatively, a Cold Fish. The strength game gave her back Weak both times.

Well, I’m only twelve, she thought.

She put both her hands in the Perfect Match to see what that did.

Soul Mates!! it informed her brightly.

I like myself, she decided.

She put coins in the Make-A-Wish. She didn’t like the creepy magician-thing in the Make-A-Wish. It was blue with a turban and its eyes lit up. Still, she had done everything else, even the photo booth. (She’d left the pictures on the floor. She hated her hair.)

I’d like to go home, please, she thought.

Well, not home, she amended. “Home” was a big house in a different world and the people there didn’t like her anymore. She wasn’t too terribly fond of them either.

I would not like to go home, she informed the blue magician, pointing a finger. I would like Barnaby and David to be done drinking and come get me. She hit the big gold button that said WISH on it.

The eyes lit up. The mouth opened and closed.

It dispensed a small slip of paper with black script: Patience is the most difficult of virtues.

“You wanna ask the Roll-A-Dance what I do to obnoxious machines?” she said, threatening with a fist.

The blue figure inside regarded her placidly.

She smiled a peculiar, twisted smile. She fed in a few more coins.

“I would like David to be normal, please,” she said. She hit the button.

The eyes lit up. The mouth moved. One of the eyes lit up slightly brighter than the other one and then went out. The mouth unhinged. The faint purple smoke of a dead enchantment curled up from behind the figure. The figure tipped over sideways and rested its forehead on the glass.

The paper dispensed had been improperly trimmed between two fortunes. The top one was Reply hazy ask again later, the bottom one appeared to be something about sardines.

“Serves you right,” she told the machine.

She ended up curled and sleeping on the bench inside of the photo booth.

The arcade was open twenty-four hours, but the attendant did make occasional rounds to clear out the undesirables. He found her in there and asked, “Little girl? Do you have a place to sleep tonight?”

“My father and his friend are in the pub,” Hyacinth said. “My father has long black hair and a purple coat.”

Her father had short, ash-blond hair and wouldn’t have been caught dead in a purple coat. He liked chequered riding jackets.

She reached into her dress and drew out a ten. “Could you take this and tell him I’m in here when he comes to get me?”

The man nodded, accepting the bribe. This wasn’t the first abandoned child he had found under such circumstances, though it had perhaps been the wealthiest. “Last call’s in about forty minutes,” he told her.

“I just hope they don’t go to the zoo,” she said fuzzily. She pillowed her cheek on her hands and shut her eyes.

It was probably after last call when they came to collect her. It seemed they had not gone to the zoo, at least they didn’t have any animals on them. They were speaking in what they thought were soft voices and trying not to wake her. She pretended they didn’t so that she wouldn’t have to deal with them.

“She looks like a little princess!” David said. “Oh, Gray, I feel dreadful. What’ve we done?”

“We took her to a movie and we let her entertain herself for a few hours, that’s all,” Barnaby said, lifting her. “She had fifty sinqs. She could’ve had a taxi home if she wanted it.”

“Oh my gods, don’t say that! I would’ve been frantic! What if we got home and she wasn’t there?”

“Not be there? Why wouldn’t she be there? Where else would she go?”

“What if somebody stole her?”

“What would anybody want with Hyacinth?”

“I don’t know. Something awful, I suppose.”

“You worry too much, David.”

They put her on one seat in the taxi and covered her with a lap blanket. They shared the other seat. The ride was bumpy, but a little bit soothing. Like being rocked. The motion of the carriage kept nudging the top of her head against the cushioned door.

“Thank you for rescuing me, Gray,” David said softly.

“Are you rescued?” Barnaby said. Perhaps there was an unspoken reply to this. “Will you stay rescued?”

“I don’t know…”

“Will you try, please?”

“I always try.”

Silence, for a time.

“How’s your hand?”

“Stings a little.”

Barnaby shifted and put his feet on the seat next to Hyacinth. “It’s going to be hell to pay with my wife, you know. We were going to dinner.”

“Oh, when are you going to leave that insufferable coiffured old sow and come and live with me?”

“I love Veronica,” Barnaby said weakly.

“She doesn’t love you.”

“No, David. She doesn’t love you.”

“Do you love me, Gray?”

Another brief silence.

“Let’s not get into that again. I’m willing to put up with you.”

“Why do you put up with me?”

“Force of habit?” Barnaby said. He sighed. “I don’t know. I suppose someone has to. Oh, thank gods, here’s the house!”

“Don’t wake our Alice,” David said.

Barnaby promptly banged the steel plate in her head on the taxi door. He got it exactly.

Hyacinth roared to furious life. “Stop trying to be gentle with me, you awful, fatuous old men! You’re going to kill me! Put me down!”

She kicked Barnaby in the shin and planted both of her blue-slippered feet on the ground. “I can take care of myself, can’t I? Don’t I have to often enough?”

She snarled and pointed a finger at David, “And my name is not Alice!”

She picked up her dress in both hands and stomped to the front door. She didn’t have to unlock it. She undid the metal and left it hanging open to the street. They could hear the “fuck you!” all the way from the taxi. She immediately began to remove her dress.

“She’s better when she’s rested,” David muttered. “I think we had her out a bit late.”

“She’s better when I haven’t hit her in the head,” Barnaby added, rubbing his shin.

David smiled and decided, “Let’s be nice to her, Gray! We haven’t been very nice to her at all.”

“How shall we be nice to her?” Barnaby said.

“I could buy her a pony,” David said.

◈◈◈

Hyacinth plucked the strip of photos off the wall. There were four, approximately identical. The subject was a frowning blonde girl with a complicated hairstyle of twining strands and spiral curls.

Only the second one had frozen with her looking at the camera. In the other three she had rolled her eyes either up or sideways. She appeared impatient with the entire process and a little bit gaunt, with hollow cheeks and dark circles under her eyes.

Barnaby had a tendency to collect dirty dishes in his room, among other things. Hyacinth was removing them with the aid of a basket, and making a cursory check for dead animals. It was hard finding anything in there with all the papers. He had boxes and boxes of things. Only select individuals were stuck to the walls, generally in themed clusters. The mirror above the dresser was entirely covered with notes and snipped-out pieces of newspaper and various other ephemera related to mirrors, for example.

This particular collection seemed to be related to head injuries. There were notes on her and Erik, some astrological charts, and other pieces of random crazy.

An ad for Thackery’s Machine Oil had been pasted slightly off-centre and scrawled over with a note: More like an assist! A newspaper photo of a girl with braids sitting in broken glass and bawling was overwritten: St. George (radio). Other notes wondered: Central theme (mirrors, duality) or lazy plot device? Possible seasonal variance (brain damage season)?

A sticker bearing a smiling green face with spiral eyes opined: Sometimes a little brain damage helps!

There was a note on the back of the photo strip too: Apr. 7, 1342 — 4 = DEATH! Write photo booth company immed. requesting strips of 3 or 5 photos!

Hyacinth flipped the photos back around to the front and regarded them with a snicker.

I left them on the floor. He saved them. All these years.

And then he had incorporated them into an unflattering collage about brain damage, but the original intention was sweet. Probably. It was also possible he had saved them specifically for the brain-damage collage, or with a vague inkling that he was going to want them for something like that later.

“Hey, Barnaby, do you mind if I show these to the kids?” She had just been telling Erik about how she hurt her head, he might be interested in a picture of her from right around when it happened. And Maggie would probably like to see her in a princess dress with complicated hair and laugh at her.

Barnaby was attending fussily to another arrangement. He was willing to allow Hyacinth to neaten his room to a certain extent because otherwise it started to smell funny and he didn’t seem to be able to prevent that on his own, but it embarrassed him.

He would not leave the attic and allow her to do it alone, because she might throw out something important, or move something, or do some other upsetting thing that he needed to prevent, but he didn’t like to watch her.

Strictly speaking, he didn’t need to watch her. He knew she had taken the photos without looking back at her. It was in the way these magazine clippings had slid down. They needed the charms redone.

Also, they were bringing back crème brûlée on the tasting menu at the Swan next week. And the General was not to be allowed in the kitchen for… Ten to seventeen days? Huh.

“I mind that you have removed them, Hyacinth,” he said. “I put them where they were because I wanted them there. But now that you have done that, I don’t mind it more if you show them to the kids, no.”

He had just removed an ad for perfume featuring two identical women in identical party dresses standing back to back. He had labelled these women Jasmine and Hyacinth. He did not have an actual picture of Jasmine and Hyacinth, obviously. Hyacinth had burned her past to the ground and salted the earth.

He respected that about her.

Ten to seventeen days? he thought. I wonder if I can clear that up a little. What’s a good number?

Still holding the ad, he retreated to his desk to do math, or something approximating math. Math-association, maybe. He couldn’t redo the charms on the magazine clippings until he had a good number.

“Why did you save them?” Hyacinth asked him.

I should tell her it was just for the collage. Tease her a little.

Instead, he told her the truth, “We didn’t have any pictures of you. David wanted to cut them up. Two and two. In half. There were already four of them and he wanted to use scissors. I intervened on behalf of your health. I kept them at my house so he wouldn’t.”

“Thanks. I guess.”

He waved a hand. “Think nothing of it. Anyone would’ve done that.”

She shook her head with a smile. No, Barnaby, she thought, they really wouldn’t have.