Erik and Magnificent were in the kitchen making peanut butter and jelly sandwiches. Not so much to eat them as to engage in the process and design. The bread was getting kind of stale, anyway.

“You should put your initials in the peanut butter, that’s lucky,” Magnificent opined, sucking fingers. “Or you could just put a heart.”

He was lots better with words now, but making letters and reading them was hard for him. He needed the practice, but it upset him when he got things wrong. Maggie didn’t like that.

“Sometimes I just put a heart,” she said.

Erik considered the bread, frowning. He methodically traced an E with the blade of the knife, and after a moment’s thought he put a W on top of it.

He had reversed the E, but Maggie didn’t mention it. He got everything else right — without copying! — and he managed to keep it on the bread. “Now you can eat your name,” she told him.

“Is that lucky?” said Erik. He pressed a second piece with grape jelly on top. This jar was almost empty and they’d be using it for a glass soon.

“I dunno. Maybe it’s just interesting.” She put an M on one slice and a D on the other and made a triple-decker. “I don’t have my daddy’s last name. My mom says we don’t do that.”

“I don’t know what last name I have,” Erik said.

“Not your uncle’s?” said Maggie.

“Uh-uh. That’s Eidel. I guess Weitz is my mom.”

“Your uncle and your mom should have the same name,” Maggie said.

“How come?” said Erik. “Uncle Milo and my mom don’t have the same name.”

“Oh, it’s like that,” said Maggie.

“Like what?” said Erik.

Hyacinth came up from the basement and asked Erik if he was ready to try out his new eye today.

Erik sat up and clapped his hands. “Really? It’s all… done?”

Magnificent covered a snicker. She really shouldn’t laugh about it, but it was funny. You could only notice it now because he was getting better and he didn’t struggle so much. He still talked sort of slow, but he got slower when he was excited about something.

He used to get faster. Faster made sense. Slower was hilarious.

Hyacinth shook her head briefly at Maggie, then addressed Erik with a raised finger and a smile, “We do still have to fit it to you. And I keep telling you, Erik, you’re not going to like it right away.”

“But I can… start liking it… right… away!” he said.

“You can start not-hating it, I guess,” said Hyacinth.

“Miss Hyacinth, can I come too?” said Maggie. “I want to see.”

“Yes, but you’d better ask your mother. You’re almost out of time for lunch.”

“Ooh, that’s right!” Maggie ran.

“Can I… take my… sandwich?” said Erik.

“You can take your sandwich, but please wash your hands. Milo and I don’t want a peanut butter and jelly worktable.”

Erik grinned, shamefaced. He licked his fingers first.

◈◈◈

Maggie barrelled down the stairs with one hand hooked around the banister. “Mom says I can have independent study, I just have to write a paper about what I learned!”

Hyacinth smiled and nodded. That woman is bizarre, she thought.

And she is going to work that poor child to death.

Milo dropped the eye on the worktable. He gasped. It bounced and then rolled in place, being slightly off-round.

“I’m sorry, Mr. Rose,” said Magnificent, looking away. “I forgot you were down here. I won’t talk to you.”

Milo breathed a sigh and twitched a small smile. It wasn’t that he didn’t want her to talk to him at all — she was just a little loud — but if she wasn’t going to talk to him at all, then he didn’t have to worry about it.

He picked up the eye and felt over it with quick fingers, checking for damage. It should be sturdy enough to take a little fall like that, and it appeared to be, but any dents or chips might hurt Erik. He gave it to Hyacinth so that she could have a look as well.

Hyacinth turned it over once in her hands and then offered it to Erik, “Here.”

He drew a slow breath. “Can I… touch it?”

“You can hold it. Go on.”

He took it in both hands and held it cupped. It was heavy. The back of it was smooth and round. The front had a raised circle like an iris with a hole in the middle that held a glass lens. You could see a little bit through the lens and there were tiny parts and gears and things tucked away inside. The whole thing was bright gold.

“It’s not really… gold, right?” he said.

“It’s a special kind of brass that’s made to look like gold,” said Hyacinth. She glanced aside at Magnificent. “It is suitable for cheap jewellery and soldiers’ medals.”

Maggie grinned and put her hands over her mouth.

Erik held up his new eye and gazed into it, frowning. “It looks… scary. Like a bug. It’s not like my other eye.”

“It’s just complicated,” Hyacinth said. “It won’t look scary, because you’re not scary. You’ll just look interesting.”

“Can I have a grey one later?” he asked.

“You can have a silver one if you like,” Hyacinth said. “Silver still tarnishes, so the only real difference would be the colour, but you can’t have one that looks like your other eye. They make some expensive glass eyes that work the same and look very real, but you have a metal socket, Erik. A glass eye would get all scratched up and stop working.”

“Gold is so bright,” he said. It was so obvious. People would look at it. They already looked at the socket, and the patch, but they would really look at this.

He was less excited now, and more worried. It was easy to tell because of the talking. It was harder to find words when he wanted them badly.

“Gold is just perfect,” Hyacinth said firmly. “I like gold very much for a boy, but I’m prejudiced.” She smiled. “I knew a man with a golden nose, and that was real gold and it was even brighter.”

“His nose?” said Erik.

“Mm-hm. Lost it in a duel. Swords, not guns. He came from a very wealthy family, and the boys in wealthy families are always looking for reasons to duel each other. Summer is duelling season and they pop off like flies. Don’t you ever duel anyone, Erik. It is an idiotic practice.”

“Okay,” the boy said, somewhat mystified. He turned the eye in his hands.

“What was the duel about?” Maggie said.

“Oh, the gods alone know,” said Hyacinth, waving a hand. “He’d make up a different story every time. You could never get a straight answer out of David about anything.”

“Was he a nice man?” Erik asked. “Was he scary?”

“He, uh…”

You would have to undergo quite some mental acrobatics to apply “nice” to David. “Scary” was, quite frankly, a lot closer to the mark, but she didn’t want to say that. “He was interesting,” she said.

“Like how?” said Maggie.

Oh, dear. What could she tell them about David that was interesting and safe for children?

“Well, he liked to work metal, like me. And… He had lots of black hair… He dyed the grey out. He was very vain about his hair. He was vain about everything. And he had green eyes, but one of them looked black because he got punched in the face and the pupil didn’t work right anymore. He liked music. And he liked parties.”

Hyacinth pointed a finger as if she’d seen a dessert she might like coasting by in a motorized display case. “One time he threw this party where an elk got drunk and fell down the stairs,” she said.

That was safe for children, she’d been a child when it happened!

Magnificent giggled. “What?”

“Oh, I’m sorry, does that need explaining?” said Hyacinth, with a smile.

“Why was there an elk?” said Erik.

Hyacinth had to think about that. After spending some time with David, you learned to stop wondering why. “I believe that the elk was there because it could roller-skate. Or they said it could, anyway. But I may be thinking about a different party, and maybe it was a horse…” She glanced at Erik, but he showed no distaste.

“Was the elk okay?” he asked.

“Er, yes. We fixed it and it was fine.”

They fixed it with potatoes and it was delicious.

There had been a war on. Not a big war — a just a bunch of dumb kids trying to start a revolution that was over within the year — but it still would’ve been unseemly to waste an entire elk. Across all classes, Marselline people were proud of their tendency to eat whatever was handy, as long as they could scrape together a decent béarnaise.

“Um,” said Erik.

Hyacinth plowed onwards before he could protest, “Anyway, he liked parties. His name was David Valentine, except it probably wasn’t, really. Sometimes he’d say David Dickenson or David Crisp.”

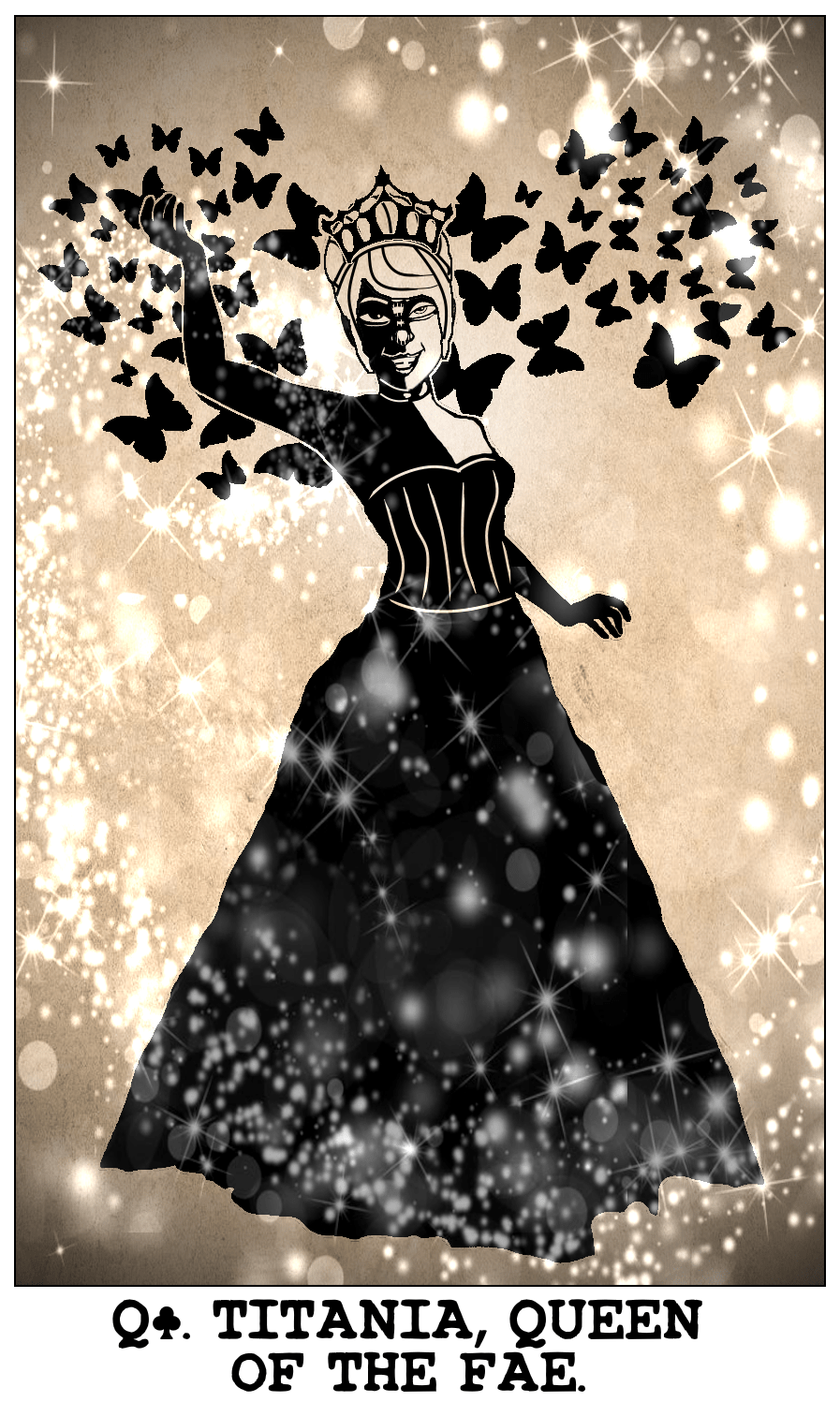

And sometimes, she added quietly to herself, Titania, Queen of the Fae.

“He put a steel plate in my head. Saved my life.” She knocked one hand against the metal. It sounded not unlike a hard leather shoe giving a tin can a swift kick. Her flesh really ought to muffle it beyond recognition, but magic could be silly like that.

“And later I went and lived with him,” she said. “He had a great big house in the country, but he liked the city better. He was…” Oh, she still couldn’t see her way around nice, “fun. He was just a little bit silly sometimes.”

“Like how?” said Maggie.

Hyacinth grinned. “Should I do it?”

The children looked up at her.

“I think I’ll do it.” She pulled the tie out of her hair. She did David very well. She was often asked to do David at parties, sometimes even by David himself.

“You know, I said he was vain. Sometimes he’d get very depressed looking into mirrors and he’d go…” She clutched her fingers into her hair and threw her entire body backwards to look up at the ceiling, almost the full ninety degrees, “‘What’s the point of being alive if I can’t be…’” And here she flung herself forward so that she was staring at the floor with her hands pressed over her face and her hair hanging down like a funeral veil, “‘Gorgeous!’”

Magnificent giggled. Erik looked amazed.

“Or he’d be at a party, he’d be having a perfectly nice time, and all of a sudden, he’d grab a knife or something… I mean, even a table knife… or a letter opener…” She picked up a screwdriver from the worktable and held it to her throat. “And he’d say,” she flung her head back again and combed her other hand through her hair, “‘Oh, gods! Kill me now while I’m young and beautiful!’”

She put down the screwdriver, snickered, and tied back her hair. “But you have to picture it with lots more hair. It’s much more dramatic with lots more hair.”

“He sounds funny,” Magnificent said. She waggled her hand to imply, although at nine years old she couldn’t have had a terribly good idea of what she was implying. She probably just meant like Milo.

“David Valentine was too fabulous for one gender,” Hyacinth said firmly.

“Did he wear dresses?” Maggie asked.

“Yes, but not like Ann,” said Hyacinth. “Ann is very tasteful and understated.”

Milo, who had been edging away from Hyacinth’s weird behaviour, looked up. He looked confused.

“It’s true, Milo. When Ann goes out in dresses, people maybe look twice. When David went out in dresses, people would walk into lampposts. Ann looks like a woman. David looked like a chandelier.”

Milo sat on the edge of the worktable and considered this with a hand to his mouth. But Ann had work dresses with sequins.

“David had a dress with electric lights and magic paper butterflies,” Hyacinth told him.

Milo opened his mouth and closed it. He had nothing at all to say to that.

“Auntie Hyacinth?” Erik said weakly. He was holding the eye and looking into it again.

“Yes?”

“Do I have to be that interesting?”

“Oh, no!” She knelt down beside him and hugged him. “No one should be that interesting. David was like a real unicorn. Something the gods let go by mistake. You should only be a very little bit interesting. Maybe you could collect stamps or something.”

“Stamps,” said Erik, considering it. Well, he liked it better than electric dresses.

“I am gonna write the best paper ever!” Magnificent declared, hands clasped and eyes worshipful.

“Maggie, you can’t write your paper about that!” cried Hyacinth.

“Sure I can! If Mom doesn’t like it, she can get stuffed. I’m learning things!”

“No-no-no,” said Hyacinth. “Look!” She snatched Erik’s eye from him. “Look how we’re going to fit this for Erik. That’s very, very, very interesting!”

Milo shook his head at her. Even I’m not buying that, Hyacinth.

“Milo, Milo, hand me… hand me the little metal measure things.” Calipers. They were calipers, and he handed them to her. She demonstrated their function to Magnificent. “Wow! These are… Precise!”

Magnificent pressed a hand to her mouth, hiding a laugh. “Um. Yes, Miss Hyacinth.”

“My gods, you are patronizing me,” said Hyacinth. Did she honestly used to think this child was polite?

“Oh, no, Miss Hyacinth. I’m not! Those are very nice, um, tools! Please show me how you fit the eye.”

“You’re going to write your paper on whatever the hell you want, aren’t you?”

“Yes, Miss Hyacinth,” Maggie said.

I should tell her lots more about David, Hyacinth thought. Let’s blow her mother right out of the water.

Instead, she said pettishly, “Well, I will show you how we fit the eye, but only because we were going to do that anyway.”

She handed back the calipers. “Milo, here. You’re better with numbers. Measure and write it down.” His inability to communicate only extended so far as words. He drew her a lovely little diagram which showed exactly what needed to be done and exactly where it needed doing.

“Well done, Milo,” she said. She pulled down her goggles. “Bright lights, everyone.” She waited until they had turned away. It only needed a little adjusting: more metal here, less here. They could get an even better fit after he’d tried it on and worn it for a while.

It was going to take a lot of practice before he was wearing it for any amount of time. He really wasn’t going to like it right away. What had begun with entertaining tales of suicidal ideation would end in terrified little boy tears. Still, there was no help for it. It had to be done sometime.

“Erik, are you all done with your sandwich?”

“I forgot it,” he said. It was still on the worktable, on a folded paper towel.

“Well, we’ll leave it. I think that bread is stale, anyway. Do you mind if we sit you on the table?”

“No, it’s okay.” She helped him up.

“Maggie, this part is scary,” she warned. “Erik, I know you don’t really believe me, but this part is scary. It won’t be forever, and we’re all going to be right here and we’ll fix it.”

“I think I… believe you… about how it’s… scary,” the boy said, knotting his hands in his lap.

“I’m sorry, honey,” Hyacinth said.

Maggie put hands over her mouth again, but the laugh was nervous this time, and she stifled it entirely. He slowed right down when he was scared, too, and that wasn’t funny.

Hyacinth held the eye in her fingers, held it up. “Ready? Okay, deep breath. There!” It clicked right into place when she pushed it in. Milo really was excellent with numbers.

Erik straightened suddenly as if electrified. He gasped and clapped a hand over the eye, making it dark. “No!” he said.

“Erik?” she said gently. “Honey? You need to take your hand down.”

He shook his head wildly. He could feel the thing spinning against his palm and he could hear it clicking and chattering in his head.

He had seen… Nothing. Something. It had been bright and it hurt. It made a sound in his head like grinding gears and he had wanted to scream. “I want to… take it out. How do I, uh, uh… take it out?”

“I will show you, but not yet.” She began to pull his hand down.

“No… please…” He fought her. She forced his other hand down and then she continued to pull the hand from his eye. “No… please… don’t… hurt… me…”

“It’s not forever,” she said.

“Please… please…” He saw light, and he gave a reflexive little shriek. The eye whizzed and shuddered. “Stop!”

Milo grabbed his shoulders and held him, and Hyacinth pulled his hands down.

It was…

Light. Shadow. A pattern of bars stuttering and endlessly repeating. Horizontal. Vertical. Diagonal. His eye clicked back and forth, tracing them, echoing them

It might not have been so bad if he wasn’t seeing actual people and faces and things with the other eye. They meshed and overlaid and interfered with each other. They distorted. Eyes widened and fell back into darkness. Mouths gaped. The corners of things warped and bent unnaturally. Shadows grew out of the walls and bled to the ceiling. Light flickered and turned colours, some colours that weren’t even colours!

And he heard noises. How could he be hearing noises? It was just his eye. There was a high, thin shrieking sound in his head that stuttered and warped with the light.

Oh, gods, he thought. I smell toast. I think I’m dying.

He turned his head aside and, with considerable effort, he shut his good eye. It wanted to be open and follow the bad one. He forced it closed. It darkened. Then he only saw lines and bars and heard noises.

And smelled toast.

“No, Erik. Both eyes open.”

He shook his head. No-no. Not happening. No way.

Hyacinth put her hand up and pried his eye open.

Evil, he thought.

It started all over again. He was crying and pleading with them, but they wouldn’t do anything. Even Maggie wouldn’t do anything. They just held him and made it happen. Hair grew out of the walls and there was a violent shade of green that was screaming and spiders poured over everything and it was only light and shadow, why did it look like that?

The noise grew less. Not in his head, not the screaming in his head, but the clicking and whirring in his eye. It was moving less.

It showed him things in recognizable patterns. It followed the mortar in the brickwork of the walls — stepping down, stepping up. It traced the lines of the planks in the ceiling. It went up and down the banister. It found the shadows where the walls came together and made the box of the room.

Finally it showed him Hyacinth’s face, not as a face, but as a series of lines to follow. Up. Down. Around. It made him feel dizzy, but that was better than feeling insane.

“Erik, can you follow my finger? Try.” She held it in front of him. First his eye followed the line of it, up and down. She moved it slowly and he began to track the motion, stuttering at first and then more smoothly.

“Is that a little better?” she asked him.

She flickered. Colours intruded, and occasional sound. Half of her face vanished briefly and her eye was left floating in empty space. Sometimes he saw her teeth moving without lips.

But, yes, that was better.

“Can I… have it… out now… please?” he whispered. “Please?”

“Yes,” she said.

He began to weep with relief.

“Erik? I’m going to show you.” She moved his hand for him. “Hold your hand like this. Put two fingers on your eye, but don’t press, just touch it. Now, you’re going to bring your head forward quickly. When you feel your eye come forward in the socket, grab it and take it out. Don’t force it. It should come easily. You might have to try a couple times. Ready?”

He got it on the first try. He pulled his hand back and attempted to throw it away, but Hyacinth caught him and stopped him.

“I… don’t… want… it!” he cried. “I don’t… need… two… eyes!”

Hyacinth said, “If you were older, Erik, I would have to listen to you. But you are seven, and that is too young to decide you want less of something just because it’s hard right now.”

“I… hate… you,” he said. “That’s not the… radio, that’s me!”

She nodded. “That’s okay. You can hate me just as long as you like. But you’re going to learn how to use your eye.”

He pushed her away from him and he slid down from the table. He was shaking too hard to stand, and he went down on one knee.

Milo was on the floor under the table, hugging his knees and crying silently. His glasses were all steamed up.

“I,” said Erik. “I… I don’t like you… either!” He felt bad about that right when he said it, but he wouldn’t take it back.

Maggie put both arms around him and helped him up.

“I’m… mad at you,” he told her. He said it softly, because she was holding him and he had to say it right in her face.

“I’m sorry,” she said.

“Why didn’t you… save me?” he said.

“I didn’t know you needed saving.”

“You… should,” he said. “You should… know stuff.” He pushed her away. “I can walk.”

He couldn’t really. He stumbled. When he got to the stairs, there was a banister and that helped. He remembered having to look at the banister, over and over, and when he looked at it again, he winced. He looked away from it while he climbed.

“I’m not gonna write my paper about that,” Magnificent said, watching after him.

“No,” said Hyacinth. “We’ll write a very nice report about David. I’ll tell you some more stories, but I think I’d better do something with Milo first. You go on upstairs. I’ll be along.”

Milo covered his eyes and curled up tighter when she touched him, but she pulled him out from under the table anyway. “You don’t have to look at me. I’m not going to talk. We’re going to your room, that’s all.”

Head hanging, he nodded.

She walked him up there, she opened the door for him, and she released him. “Thank you very much for helping me, Milo,” she said, looking away.

He shut the door. He didn’t look back.

◈◈◈

Milo crawled into the closet and sat there among the clothes and shoes and darkness. Alone. Breathing hard.

I shouldn’t have done that. I shouldn’t have done that. I screwed up. I hurt him. He hates me. I’m so stupid. I’m so fucking stupid.

They weren’t going to hit him or take things away from him, they didn’t get to do that anymore.

But that didn’t make it okay.

It was worse because he wanted them to like him.

I don’t like them.

I like them.

I’m sorry.

He buried his face in the skirt of one of Ann’s dresses and cried. He couldn’t make noises, not him, not even when he was alone, and that just made him cry harder.

Then he was done. He didn’t feel better, but when the fear and shame got stronger than the need to cry, he’d click off like a switch. It always left him feeling empty and confused.

The dress was damp and he knew he needed to wash it, but there wasn’t any water up here. All the water was in the kitchen with people. He sat on the floor of the closet with the rumpled dress in his lap and thought, But we have so many pretty dresses, Ann. That’s good, right?

Don’t we have all the pretty dresses you want?

◈◈◈

Erik went back to his room. It was dark and quiet and there was not much to look at. He loved it instantly. He slipped off his shoes by the door, and crawled into the big bed next to his Uncle Mordecai.

“Huh?” said the man.

“I like it here, okay?” said Erik. He hid his face in the blankets and shut his eye.

“Erik? Did something happen?”

“No.”

“Erik…”

“I had a… peanut butter and jelly sandwich. Maggie said put… letters in the peanut butter. I put an E and a W and I didn’t mess it up even a little.”

“That’s good,” said Mordecai.

“Yes. Can I stay here forever?”

“No, dear one.”

“Then how come you can?”

He sighed. “I can’t stay here forever either.”

◈◈◈

Magnificent went into the alley through the kitchen door and deconstructed small items for her own amusement.

◈◈◈

Hyacinth went into the kitchen, put all the milk in one large pot and made hot chocolate. As the others trailed in, one by one, she served it.

Erik and Mordecai came in together. Mordecai was dressed — a shirt (it was untucked), pants and, she was pleased to see, shoes. It really wasn’t safe to be going around this house in stocking feet, no matter how unhappy you were. Even Barnaby wore slippers.

Mordecai nearly hit her when she told him she’d let Erik try out his new eye without him. It wasn’t very nearly — and Erik agreed that he didn’t want to look at his uncle with his new eye until it was a lot less scary — and soon they were both sipping chocolate quietly, if a little bit sullenly.

Maggie came in next, and she didn’t require much persuading. She apologized to Erik again and sat with her toes perched on the crosspiece between the chair legs.

Ann came down wearing one dress and carrying another. She had on the right outfit for the day (it was orange) and she was combed and painted and impeccable, but missing her usual smile. She apologized extravagantly on Milo’s behalf.

Erik apologized too. “I shouldn’t’ve said that. I know you didn’t hurt me to be mean.”

“Did he really hurt you?” Ann cried, and was almost really crying.

Erik was plumbing the depths of his cup. “It was just scary.” Hyacinth topped him up with a wooden ladle.

Ann wanted to wash her dress. Hyacinth wanted her to drink hot chocolate, but she was too afraid to wash Ann’s dress for her. Ann’s dresses were made of tissues and fairy dreams. She finally offered to give it a rinse in cold water so it wouldn’t stain.

That was accepted, as was the chocolate.

Hyacinth hung the dress gingerly over the back of a chair. When she looked up, Barnaby was there.

“What’re you doing here?”

“I saw hot chocolate,” he declared.

“Are you sure you didn’t just smell it?” Hyacinth said.

“All the way from the attic? Don’t be absurd.” He sat down at the table, anticipating service. “There was a hot-chocolate-shaped cloud.”

“What exactly does a hot-chocolate-shaped cloud look like?” she asked him, presenting a cup.

“It’s complicated,” he said. “You wouldn’t understand.”

“Hey, Barnaby,” said Hyacinth, “you remember David, don’t you?”

“David?” he said. “Our David?”

She nodded.

That damn mouse, he thought.

“I’m not sure those are memories,” he said.

“Tell Magnificent something about him. She’s doing a paper about interesting people.”

“Interesting people?” He peered narrowly at the child. “David Valentine was out of his tiny little brandy-addled mind.”

Maggie blinked.

“I was thinking more like something cute and amusing,” Hyacinth said.

“Cute?” said Barnaby. He sipped his chocolate. “One time he got into a fistfight with a nun.”

“Whaaat?” said Hyacinth. “He never told me that!”

“He never told you because he lost. Oh, it was touch-and-go for a while there, but once she started pulling his hair, it was all over. She sat on him. She had him saying Hosannas in the middle of the street. She only let him up when he started confessing things.”

“What was he confessing?” Maggie asked.

Hyacinth put up her finger, “That! …is not necessary to the story.”

“He found out what church she belonged to and he bought them a pipe organ,” Barnaby said. “He said any god with followers like that was a real up-and-comer and he wanted in on the ground floor, so to speak.”

Maggie got up from her chair. “I think I should be writing this down.”

“Who is this person?” Mordecai said.

“David,” said Hyacinth. “I’m certain I’ve mentioned him.”

“You said he taught you about metalworking. You never said he punched a nun.”

“Well, I didn’t know about that part.”

“I am aware of some nuns that could stand punching,” Ann said, nodding. “They are a vicious people. I believe they hope the gods will have them because nobody else will.”

“Nuns don’t tip well,” Mordecai opined. “A nun once gave me a phony ten sinq note with prayers on it.”

“Auntie Hyacinth,” said Erik, “tell them about the elk.”

“He punched an elk?”

“No! It just fell down the stairs.”

“By itself?”

“Well, it had been drinking vodka all night.”

“Miss Hyacinth, please spell ‘wud-ka’ for me.”

“V-O-D-K-A. I was just being cute, it’s from Prokovia. The elk was drinking vodka and cranberry juice.” It was funny how these things came back to you.

They drank hot chocolate, they talked about David, and they put Magnificent’s paper together for her. Somewhere in there, when nobody was paying any attention, they all started to feel quite a bit better. Happy, you might say.

It would be hell to pay when the General got a hold of that paper, so they might as well be happy now.

“Did you fill the coffin with glitter?” Erik asked her.

“Oh,” said Hyacinth, blinking. She didn’t… No, she didn’t say he was dead, but she didn’t have to, not for Erik.

She remembered opening all that damn glitter, and she didn’t like to.

He covered his mouth with both hands. “I’m sorry. What did I say?”

“No,” she said. “No. Nothing. It’s fine.” It wasn’t his fault. He just knew things sometimes. “We… Yes.”

“Funeral director had kittens,” Barnaby muttered. “Sparkles all over the place. Looked like a queer pride parade exploded.”

“Aw, he died?” said Magnificent.

“Yes.” Hyacinth got up and started putting cups in the sink. “He… I mean, really, he was bound to.”

“How?”

“Well, we told the paper he jumped out of an airship in full drag — with two Marselline flags, for Cloquette Day — and the chute didn’t open.”

“Awesome,” said Maggie.

Erik was frowning, he knew that wasn’t it. He didn’t know how he knew, but he knew.

“It was how he would have wanted to go, Erik,” Hyacinth told him, aside.

“Were you sad?” he asked her.

“Very.”

“Are you sad again?”

“Oh, not so much, It was a long time ago.” He had requested that she be devastated for a reasonable amount of time — say, a decade or so — and they were well past that now. It would be unseemly to carry on now.

Erik put his small green hand on her arm. “I don’t hate you, okay?”

“I know, honey.” She patted the hand. “I think you might later, for a little while, but that’s okay. I can stand a little hating.” If nothing else, David had taught her to ignore hysterical people telling her how awful she was.

And the metalworking.

And he’d saved her life, two times.

Okay, maybe she was sad again.

“I’ll try to be really, really interesting,” Erik said.

“You try to be you,” Hyacinth replied. “Do you want to show your uncle your new eye? You don’t have to wear it.”

“Then yes.”

“Go get it.”

He smiled at her, then he ran.

He’s gonna be okay, she thought.

Well, David would probably be proud.

She touched her ponytail self-consciously.

But he’d be so mad about my hair!